Akiz: “Being an artist means observing”

As his movie “The Nightmare” (“Der Nachtmahr”) has been shown during the “Kinorave Festival” in Kyiv, German director, painter and sculptor Akiz talks the film, being an artist and German cinematography.

Akiz during the presentation of “The Nightmare” at the “Kinorave Festival” in Kyiv

Photo courtesy of the “Kinorave Festival”

How did your movie, “The Nightmare,” became a part of this festival “Movie Rave. Young German cinematography,” and what is the idea behind the whole project?

I don’t know (laughs). I am a director of this film, they saw my film and thought that it might be nice to have it in this project. I have no idea about the background of this project, but I heard that Goethe Institute wants to open up for a younger audience. And this film, “Der Nachtmahr,” represents a gaze into the underground youth culture scene of Berlin. So I guess that was the reason.

What is the story behind the making of the movie and what inspired you?

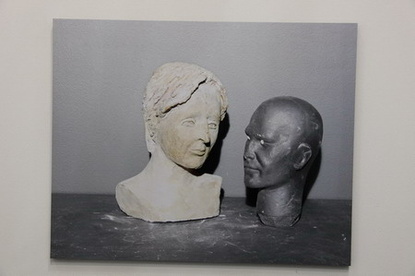

I am a sculptor, a painter, and a filmmaker and it was quite interesting, because usually as a director you have an idea, you write it down, or you let somebody else write it, and then you turn it into a movie, whereas this movie was different since before even thinking of making a movie I sculpted the demon… Have you seen the movie?

Not yet.

So this demon here (points at the poster on the wall of the cinema lobby), I built it first in clay and then in silicon, and I thought I was just going to do some photos with it. And then it evolved into a creature that can move; I put in joints, so I thought I might do a short sequence of demon riding in a car with a girl. During the time I was working on the creature I took down a lot of notes, a lot of scribbles and ideas that arose around this creature, without having a plan to turn it into a film. But then after a long-long time (this took me like 12 years or something because I was not constantly working on the film) I found myself surrounded by lots and lots of ideas and moments and scenes and I thought they somehow belong together. So I tried to find a timeline and put as much moments and scenes that I wrote into this timeline as I could, and it started looking to me like a story. That’s when I started writing it down as a screenplay. And then I tried to finance the movie, but in Germany, we have a very conservative film industry so you either do a comedy, a kids movie, a social drama, or a political movie that deals with Germany’s past. But this film, this story clearly does not fit into any of these categories. So I couldn’t raise the money, but since I have a lot of friends and I had the creature, and I knew a lot of actors, I called them up, and we made a film without any money. That’s the story behind the film.

What is the movie about?

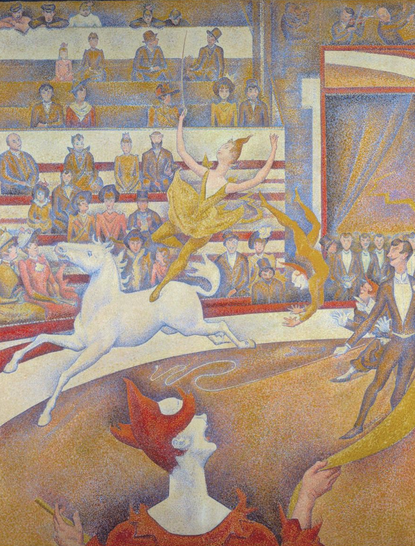

“Der Nachtmahr”, the name of the film, is taken from an old 18th-century painting by Heinrich Füssli and it is the name of a creature that appears at night and haunts people. The story is very easy: there is a party girl and after one party night she has an encounter with a demon. But rather than a regular horror movie, which works like this: there is a demon, it haunts you and you have to kill it, sooner or later, this story is different, because Tina (the main character, played by Carolyn Genzkow — ed.) realizes that the creature doesn’t really harm her, but rather represents her own feelings. So she has to come to terms with this creature, rather than kill it.

So the demon doesn’t nessesarily mean something evil for you?

Yeah, you can say so. You can totally say so, but it is, of course, ugly and disturbing, pathetic and annoying and she has to come to terms with it. If you’re going to watch the film, you will realize that there are different interpretations of what the creature represents. Because it is kind of twisted a little bit, it is a clear story, but it has some twists and turns. Some people said the whole film looks like a dream, another person said that for him the creature reminds him of Hades. Somebody else said it represents bulimia because Tina is very slim, the creature eats all the time and at one point she is throwing up. And some other person said it is about an unwanted pregnancy because the creature looks like a fetus.

When I watched the trailer, I thought the movie was about youth and about…

...rave culture.

Yes, but after I watched a documentary on the making of this movie (“Der Nachtmahr und wie er in die Welt kam” — ed.), from the small parts that I saw, it started feeling more like a film about not being understood.

Yeah, that’s your interpretation.

And what is it about for you personally?

For me personally? You know what, I’m really excited to hear people’s opinions like yours, but I’m not giving my own interpretation away because I don’t want it to become the only right one, so that everybody else would say “Okay, then mine is wrong.” That’s not the case, I want to leave it open.

So you’re giving people the freedom of interpretation.

Yes, absolutely. These are the films that I like, you know, where I can come up with my own ideas.

As you said and as I had noticed, your approach to the making of the movie was not only about directing but more of a mixed media.

Mixed media? Well, yes and no. In the end, it is just a movie, you know, like any other movies. But I was was working in lots of different fields: I wrote the story, I’ve made some music parts, I edited it, I built the creature… But then it’s just the movie.

Did you write the music as well?

Yes, I did some parts, for example, the rave in the beginning was mine. But I didn’t make the more important parts. I would say, I did about five or six minutes of music for this film, the rest was done by Steffen Kahles and Christian Blaser.

This movie is a part of a trilogy.

It is, but, again, not intentionally. It wasn’t like I had the idea for the trilogy and then I started with this one. It was rather like I made this film and a friend of mine, a musician and an artist, read my next script and said “God, it’s the same story. Again a demon-like entity that haunts.” The next movie is a clear love story, but it is again about somebody coming out of nowhere into the life. And the third one is kind of the same. So I realized I can put them together as a trilogy. Whereas “Der Nachtmahr” is about birth, the next one will be rather about life and love and the third one, obviously, about death.

Will we see those characters and actors in the next two movies?

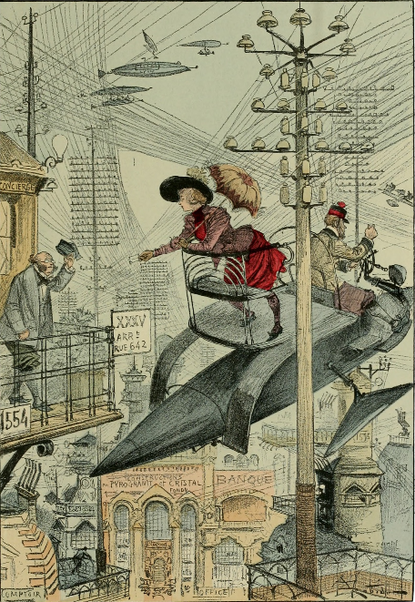

Oh, no, it is not that kind of trilogy, like “Lord of the rings” or “Star Wars.” No-no-no, the next one takes place in the 18th century, the similarities are rather conceptual. You won’t see any of those characters in the end. Caro (Carolyn Genzkow — ed.) said she wants to participate and, of course, I want to work with her because she is so great, but she will not be the main character. And you can clearly watch each of those films without seeing any of the others, not like “Lord of the rings,” part one and two and three.

Some of your short films also introduce creatures that are alike to the one that we see in “The Nightmare”, like the one, called “Evocation”. Are they some kind of a metaphor?

I feel sorry that my answer is pretty… not so glamorous or, you know, complex. I mean, as long as you’ve seen the documentary (“Der Nachtmahr und wie er in die Welt kam” — ed.), you know that I don’t have to pretend that I’m a big guy, there was a time when I was basically living on the street. So I made “Evocation” when I was working for the “Soho House,” a fancy, posh club, that I was shooting two-minutes films for. At that moment when I already had this creature, I just put two and two together… The reason why we don’t really see the creature is that at that time I already planned to turn it into a film, so I didn’t want to give away the whole physics, you can only see his back and his arm. And again you have a woman and a demon, but unlike “The Nightmare”, “Evocation”rather deals with an erotic or sexual obsession or some kind of feelings like that. But again I think I was just playing around with this creature .

May the same creature appear in any of your next movies?

No. Now it is at the German Film Museum in Frankfurt. And I’m really proud because they have this Kubrick archive, it is a part of their collection, and that’s the biggest honor I can possibly think of.

And also the night, the darkness, this kind of mystification, which role does it plays in your artistic practice?

Well, the night is something very beautiful. It is where the dreams are starting, and people fall in love and where people listen to music and dance. You don’t see anybody dancing in the bright sunshine, usually. Underground scene and youth culture always evolved from the dark. You don’t wanna go to a club or to a party when it’s bright. For some reason, human beings have a special connection to darkness and I embrace the darkness, it’s beauty. Even though “Der Nachtmahr” it not a romantic film, I like setting up my camera in the dark.

How would you define cinematography?

Well, you know I’m a sculptor, a painter, I take photos and write stories, and I like all of these disciplines. But filmmaking is the most complex one, by far, because it can include all of the others. I think, cinematography is just a language of storytelling. Painting and sculpture are only dealing with one instant. You can watch a sculpture for, like, two seconds or for half an hour, but, in the end, it doesen’t change. Whereas a story is like a history, as our human history, it is something that evolves. The only bad thing about cinematography is that it has a short shelf life. You don’t wanna watch a film that’s thirty or forty years old. You read books that are hundred years old, and they feel fresh. But if you… I don’t know what age you are, but if you watch a film from the 80s, it might look outdated and kind of boring.

Not really!

Well, what I wanna say is that films age very quickly and in novels that’s not the case. You know, you can read a book from the 20s, which was hundred years ago, and it feels like it was written yesterday. That is interesting, I think.

You also used to work as a documentalist.

I was working on documentaries, but I never finished them. I started doing that when I was living in Los Angeles, about 20 years ago. And it was more like a green card for me to get into a special kind of subculture or underground scene. Having a camera, making a documentary was kind of like an entrance. But it always felt difficult to sit down and put all the footage together and so I never actually finished a documentary. That’s a shame, but I have tons and tons and tons of film footage.

Anyway, this experience that you got, how does it influence your practice right now, when you’re working on feature films?

It does… I mean, that’s what people say. Being an artist means observing, really. It doesn’t matter if you observe real life or your own inner world, but you have to really, really look closely. And that’s what you learn when you do a documentary. It’s just beautiful, being born in an age when we can shoot a documentary with this kind of things here (points on the phone). It is amazing, it’s really a gift. But for me, documentaries were always more like a one step towards feature films. Even though there are great documentalists, like Werner Herzog, for instance. He is a master.

What are your brightest memories about working on the movie?

Thousands of, so many. There are two or three that hit me emotionally, heavily. I remember once there was a film festival in Locarno. It was summer, the August, steaming hot, everybody was kind of barely naked, walking in T-shirts, but one guy had a pullover on, he was totally covered. I saw him going to watch „The Nightmare“-screening and, because he was so thickly covered, he caught my attention. And when he came out after the movie was finished, he had just a T-shirt on, and I saw that one of his arms was almost totally crippled, very thin, like branches of a tree. But he uncovered them after the film. I was standing right there, in the lobby of the cinema, and he came straight to me. He was very emotional, almost crying, and he said: “I know what the film means, it means, you should start loving yourself.” And that touched me really-really heavily, because for him it meant you should embrace yourself, not hide or try to be somebody else and I think that is one of the biggest rewards that you get as a filmmaker.

Also, since it took me so long to make this film, there was a moment, when I realized everything really happened: I saw Caro walking down the stairs with this creature, a product of my fantasy was standing in front of me. And that was surreal for me. It was… (laughs emotionally). Yes, stories like this.

Why is this movie unconventional and why do you still prefer doing it your own way, considering all the risks?

I wouldn’t even say that it is unconventional. I think, the story is pretty straightforward. But, yes, it is. If you compare it to other German films, it is unconventional. Because German movies, I’m sorry to swear my own colleagues, but they are, kind of, like what Americans made 20 years ago. “Der Nachtmahr” is unconventional in a way that it leaves you with more questions than answers, which is an awkward, unpleasant feeling for some people. A lot of people wanna go to the movies, have a great entertainment and then close the case and leave it because there are no questions unsolved. And also there are some twists in the movie that there is no explanation for. The editing and the music is done in a kind of sometimes offensive way. Unfortunately, we had several breakdowns in the audience. There were at least three people that I know had fainted. Those stroke lights, they can cause epilepsy.

Also the music and the rave scene (and now I’m coming back to your first question about the “Kinorave”), usually music is made in a way that kind of drags you in and makes you rave in a movie theatre. But this film leads you to a moment, and I’m pretty sure everybody experienced that moment (I did, being young), when you wake up somewhere, and you don’t know who are all these people. Why am I here? How can I come back home? The person who took me with a car is not there anymore, and I just wanna go home. This movie has several moments like this. There was a young woman like you, who did an interview for an American news magazine, and she said, she liked the film and the creature because the creature made her feel like home. So all the raving, all the moving on music and everything, you like it at some point, but then it is disturbing and annoying and the creature, instead of being a horror element, makes you feel home, because when the creature is there, it is always quiet. This is like an inverted version of a horror film, because usually when the creature comes, there’s a lot of sound. So there are several moments that, I think, are unconventional. And I’m always interested, and I always will be, even more now, than I used to be before, in the things that haven’t been made before. But then it is not an abstract, avant-garde art. For me, for some people it is. But I think you can go way-way-way further.

Are you planning to go further?

Oh yes, it was just the beginning (laughs).