Oleksandr Soloviov: The main outcome of ARSENALE was ARSENALE

Oleksandr Soloviov is one of the most respected art critics and contemporary art curators in Ukraine. He was the ideologue and co-curator of “Double Game” – the special project of the First Kyiv International Biennale of Contemporary Art ARSENALE 2012. To sum up the results of the biennale he had to balance between two roles – that of a Mystetskyi Arsenal insider who knows how difficult the work was, and an independent critic who always remains detached.

The biennale is a civilizational norm. A contemporary art biennale speaks of a country’s level of cultural development. Today it’s a kind of civilizational test. It’s even a test of patriotism, because an event of this scale needs financial and moral support. Everywhere in the world there are people and organizations queuing up to finance such events. In our country, that’s not yet the case. But whether or not we need a biennale is a question of the past.

Dreams of a Ukrainian biennale appeared in the early 2000s. How timely was the First Kyiv Biennale of Contemporary Art? Were the artists and public ready? You can’t forget that ARSENALE was an institutional museum initiative. There aren’t many examples of this in the world – the famous Whitney Biennial, Tate Triennial, and that’s it. The former has only American artists and the latter is a triennial. This makes our initiative unique. The Ukrainian art community began dreaming of a biennale in the early 2000s. There was a feeling that sooner or later it will happen. In the early 2000s talk about our own biennale gained momentum. The likely impetus was Ukraine’s debut pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2001, accompanied by scandal and battles for a place under the sun. I’m mentioning this because the professional community remains divided. And this division was probably an obstacle for this major project – the biennale. In 2001, artists, critics and government officials dealing with the arts saw what a contemporary art biennale is and understood the status of contemporary art in the world. And everyone was unanimous in saying – why don’t we have our own Ukrainian biennale of contemporary art? These attempts in the mid-2000s began with gatherings at various institutions. They discussed what kind of biennale it should be, its specifics. But, unfortunately, nothing came of it. I came to the conclusion that the option that would satisfy everyone was, unfortunately, impossible, because of a constant conflict of interest. At the opening of his Center, Victor Pinchuk expressed a desire to hold a biennale in Ukraine. The art community was ready for it and full of hope. But years passed and the Center developed its own projects. The proposal was never realized and the spark of hope went out. And only with the new life of Arsenal was it actualized, because we got a truly unique exhibition space that allowed us to invite top-level curators. And what’s extremely important is the collective will that allowed the process to get off the ground.

The idea of ARENALE personalized. I want to emphasize that we owe the appearance of the First Kyiv Biennale first and foremost to its commissioner, Natalia Zabolotna. If it wasn’t for her, the Ukrainian biennale of contemporary art would have remained a dream. This ambitious breakthrough was the result of her determination. We all tried to dissuade her, saying it’s not time yet. But she mobilized and inspired the whole team with her enthusiasm.

Every biennale has its face. At the time of the creation of ARSENALE 2012 there were more than 200 contemporary art biennales worldwide, and it was important not to get lost among them, to find our own face. Every major biennale has its own specifics. For example, the Istanbul biennale took place in the plane of leftist discourse, this year’s Berlin biennale was radically political, the Sydney biennale specialized in everyday problems, there are forums on the apologetics of new media and much more. In my opinion, ARSENALE is very good name, one that appeared on its own in our private conversations. As for the concept, for the first ARSENALE we wanted to play with the topic of apocalypse as death of the old that gives hope for the emergence of something new – it’s a topic as popular as it is relevant.

David Elliott. I knew David Elliott from the exhibition “After the Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe” that he curated with Bojana Pejic. This was a major exhibition at the Stockholm Museum of Modern Art marking the ten-year anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The exhibition got much publicity because it broke the mold and introduced many new names. Elliott is a world class curator. He curated the 17th biennale in Sydney, was the director and curator of modern art museums in Stockholm, Istanbul and Tokyo. And, like any curator, he has his own geographical, thematic and stylistic priorities. David is an expert in totalitarian and post-totalitarian cultures, an adherent of fundamental generalizations. This was evident in his iconic exhibition “Art and Power” in the 1990s. That is why Elliott was the ideal candidate for us – he was fascinated with the powerful space of Arsenal. David also has the utmost respect for the context of a place where he works. He carefully studies the work of local artists, the specifics of the local environment, its history, geography and traditions. Elliott is a man of the world, he has an open worldview, he exhibits no colonialist western snobbery. He had a combination of practical global experience and theoretical, cultural background – exactly what the First Kyiv Biennale needed.

There are different trends in the world but art is eternal. It’s no secret that there is criticism of the biennale project as such. For example, the Venice Biennale is criticized for being overloaded and outdated in form, for sticking with the idea of national presentations at a time when migration and diffusion processes are strengthening, including in art. There are different trends in the world now – activism, protest, critical art. Today the spectacle element of the biennale isn’t as important as the depth, as activity rooted not in exhibitions but in society. Art is losing its exhibition shell, what Virilio once talked about – the delocalization of art. Given all this, Elliott was asked if he wasn’t afraid of creating just another biennale. He responded that his goal was to make a good exhibition, not embody new trends, as they say – at any price, artificially. In this separation of contemporary visual activity into activism and aesthetics, he chose the latter. But the Arsenal space had much to do with this choice. I find it hard to imagine this vast space being filled with text messages by “angry workers”. The space dictated the form. The First Kyiv Biennale was criticized for being overly spectacular, overly academic, conservative, not innovative. It was representational – founded on the principle of celebrities. There aren’t many art events in the world where under one roof you’ll find works by Kusama, Viola, Ai Weiwei, the Chapman brothers… But this was Elliott’s intention. You must admit that the concept behind this exhibition, I reiterate, fully reflects the spirit of the times. The best of times – the worst of times: an era of change, ending-beginning. Apocalypse and rebirth in contemporary art. Turning point, breaking point – this is the foundation of Elliott’s concept. And for a debut, this, in my opinion, is good – summaries of the past collected and presented in the images of iconic artists.

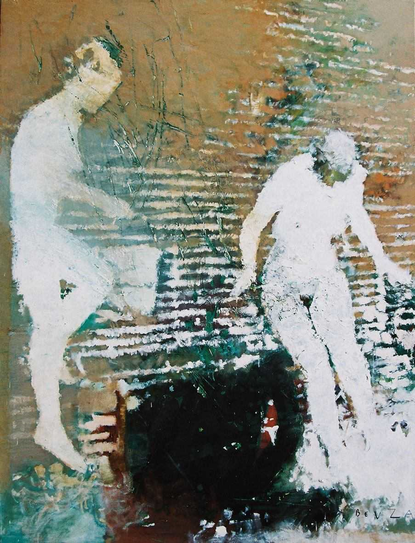

Local – global. The biennale policy as a specific artistic institution is always based on balance of internal and external interests. On the one hand, the international community aims to discover a new art resource. On the other hand, national agents want to use the global art system as a potential impulse. The unspoken quota of local artists at a biennale is approximately 15 percent. David Elliott exceeded this quota. Although short on time, David still went to Ukraine and visited artists’ workshops. He reviewed kilometers of video, traveled to the regions – Lviv, Odesa, Kharkiv. He met with artists. Held lectures, spoke with the public. The value of this is that it’s done by a curator that looks from the outside. We may not agree with his choice. We may not agree with how a particular artist’s works were exhibited, whose works were next to his. But when you start analyzing the curator’s actions, you understand they’re not random. There was Greece’s Faitakis’s iconographic work diagonally across from young Ukrainian artist Serhiy Radkevych, who also made a trinity, but in the spirit of modern graffiti. Eloquent in this sense was the area that united the sculptures and installations by British artist Phyllida Barlow, Japanese artist Shigeo Toya and our own Mykola Malyshko. They are united by the material that underlies the works – wood. Just like the room with paintings by Chinese artists and Ukrainians Arsen Savadov and Vasyl Tsagolov. The curator tied conceptual and formal knots. It was his right and decision.

One of the impetuses for us was the desire for this global event to help our local context break into the global context. This was one of the main ideas. We had to present Ukrainian artists to the world on the highly competitive background of international stars.

EURO. We had to fit into the international calendar and take into account the added interest created by the 2012 European Football Championship. Euro 2012 also opened Ukraine to the world. But, no matter what anyone sayd, the football fan, even European, and connoisseur of contemporary art are different audiences. And Euro may have worked against the biennale, not as a factor that repels, but one that certainly distracts.

Budget. Every biennale starts with a budget. The level of co-financing from the state and private sector was almost even. We relied on average figures and the experience of our neighbors. You have to take into account that a biennale is also an industry that depends directly on the curatorial concept, on the curator’s selection of works, his geopolitical preferences. For example, our curator saw Kyiv as the intersection – historical and contemporary – of different civilizational and cultural routes, but decided to focus on the intersection of East and West. Nearly half the participants of ARSENALE were artists from the Far East – China, Japan, Korea, Kazakhstan. This was David’s choice – another curator may have accented the North-South axis, “from the Vikings to the Greeks”. And this, possibly, would have reduced the logistics part of the budget, because it’s much cheaper to bring a work from Europe than from China (laughing).

Special project - zone of game and communication. During the creation of “Double Game” one of the determining factors was the immediate moment, the cooperation between two neighboring countries – Ukraine and Poland. It’s a field of cultural exchange with a special Polish guest. The “Double Game” space also became a very active zone of communication, dynamic dialogue with the spectator – there were get-togethers with artists, interdisciplinary events such as performances and music. And although the special project was held under the same roof as the main biennale project, it presented a totally different image. If David Elliott’s goal was to create pantheons of stars and split the space by individual, then we, as curators of the special project, created a field for communication, a game for its participants. This field was even deliberately united by the installation of the Polish group Centrala and Ukraine’s Grupa Predmetiv. Special exclusive works were also created for “Double Game”. The special and main projects complemented each other. But the different atmosphere and formats of these two projects created a coherent overall picture of ARSENALE 2012.

The outcome of ARSENALE was ARSENALE. It happened, and it’s already clear that it wasn’t a one-time event. The biennale interested and mobilized everyone. There aren’t many who were offended and dissatisfied – nearly all art institutions and most Ukrainian artists participated in some way. The polar assessment by the media is rather conditional, because objective analysis requires time. The spectators were satisfied. And the contempt and disdain for contemporary art by state bureaucratic institutions was overcome.

Need for distance in time. All we have now are immediate media reviews. I hope that with time there will be real analytical reviews of the works by the participants of the First Kyiv Biennale and Elliott’s curatorial strategy.

Sequel syndrome. Many are already asking about the next ARSENALE. This time we have a longer springboard for its preparation – not nine months, but a full two years.