Inventory of a Dictator

Curatorial text for the “Codex of Mezhyhirya” exhibition at National Art Museum of Ukraine

The history of the “Codex of Mezhyhirya” project dates, certainly, from February 22nd – the day of the Fall of Mezhihirya. It was on that day that the eventual co-curators of the exhibition met on Maidan, and it was there that we got a call from a well-known Kyiv journalist with the news: crowds had overwhelmed the Presidential residence bringing to light a “dictatorial treasure house whose value was incalculable”. The caller indicated some urgency in getting the hoard turned over to museum professionals. Managing to get to Mezhihirya by that evening, we were packed into a mini-bus with some Newfoundlands and their handlers, (the latter responsible for the feeding of the Central Asian Shepherd dogs from the presidential kennels), and driven along the Dnieper through darkened alleys to a garage. Inside stood an impressive collection of soviet-era automobiles – from pre-war “Yomky” pickups to the GAZ model 21. Every model Viktor Yanukovych could quite possibly have dreamt of in his troubled boyhood, including, here and there, a German make that he’d likely seen in a war film. And among all these, trucks loaded with boxes filled with valuables that had not been spirited away from the grounds.

Winking at us from the piles of Presidential detritus was an elegant candelabra made of an extraordinarily lucent golden metal more plastic than gold in appearance. It stood on a base of so-called “Ephesian marble”, a popular pattern for kitchen counter tops. We later found a case containing a document certifying that the piece was from the valuable “Deer” collection produced by a German porcelain manufacturer in 1976. Yet somehow we were still expecting to find scores of forgotten Van Goghs and Da Vincis cast aside and friendless and, of course, the much-heralded, golden commode – toilet hardly being word enough. We watched as one member of the Self-Defense squad stood in quiet awe before a contrived pitcher-with-fruit still life timidly realized by a none-too-experienced artist. In the soldier’s opinion this painting was of singular cultural significance. The remainder of the hoard had been neither uncrated nor inventoried, and those in charge of security at the garage seemed utterly unaware of what it was they were securing. There was simply no predicting what we would find next, but as we came to discover, buried among the piles of gilded bad taste were occasional items of evident cultural value. And all of it in need of immediate evacuation for safekeeping; the presidential palace was not yet secure from either spontaneous or organized outbreaks of looting.

We began calling around to the directors of leading Kyiv museums. By the next day – and over the next several weeks – a committee of representatives from major museums, operating under the aegis of the Ukrainian Blue Shield, began working at Mezhihirya. The committee included Yulia Lytvynets from the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Olga Melnyk and Viktoria Velychko from Mystetskyi Arsenal, and Olena Zhyvkova from the Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko Museum of Art. They spent considerable time negotiating and defining expectations as time and again hastily stowed candelabras and icons were continually unearthed from their less-than-conventional hiding places on the premises – boiler rooms, garages, and fruit cellars, wine cellars, and pantries. We were not afforded access to everything, some pieces having been spirited away by the former owner in flight long before the committee could begin its work.

Paintings and icons in need of removal to an adequate museum storage facility were packed quickly and prepared for transit. To mitigate any potential disorder or misunderstanding, all valuable items which had been handled by the Mezhihirya committee were inventoried and transported to the National Art Museum of Ukraine. It is fitting here to point out the selflessness and accountability of the work of these museum workers, as well as that of the Maidan Self-Defense groups who secured the Mezhihirya grounds and arranged for the orderly hand-over of these valuables for temporary safekeeping. The eventual fate of the artifacts uncovered at Mezhihirya rests in the hands of the State, but a valuable precedent was set here in the joint effort by the Self-Defense squads and the Museum staff whose efforts ensured the avoidance of any rioting in this tense, post-revolutionary setting. In the end, scattered among the sizeable collection of costly items – most of which are of marginal cultural and historical significance – were also counted and secured a number of paintings, sculptures, pieces of decorative and sacred art, as well as a number of rare ancient manuscripts of considerable value.

The true heroes of this saga of the hand-over of the dictator’s stash to the National Museum are the Self-Defense foot soldiers. The manner in which they handled “the Mezhihirya Issue” showed trued civic responsibility. It was the Self-Defense squads who first called on the museums for assistance with the abandoned loot of the previous owner. The 3rd Self-Defense sotnia, the AutoMaidan, the Right Sector, the Mezhihirya Command – all these monikers are now fixed in the working vocabulary of the specialists from leading Ukrainian museums. And those of Svitlana Karabut and Pavlo “Askold” Pavlov, Ivan Hryshko and “Wednesday” Ihor, “AutoMaidan” Ihor, and the unforgettable guard of the Mezhihirya treasury Petro “the Ghost” Oliynyk, as well as those young men serving in the Self-Defense squads who assigned real value to the objects they watched over – all are locked in memory. Their civil handling of the situation will long serve as an example for the nation. Their naïve faith in things that sparkle, joined to that powerful and authentic heroism that arises in the inevitable utopian spirit following hard upon revolution, and also to this – that the common folk, united in purpose, might mold the fate of their nation. It is to these we dedicate this project.

Much has been said already about Mezhihirya and its bizarre aesthetic. To the typical viewer, those who visited “the palace” by the thousands in the early days after it was opened to the public, the estate of the ex-President came off as some sort of novel Ukrainian Versailles. Many have written about the unblushing luxury on display at the residence. But the true defining characteristic of the place is its chaotic mounding of one style on another, its mixture of unmixables – a wooden cottage featuring a quasi rococo interior which looks out on a Parthenonian homage fashioned from concrete slab and snuggled up against a spa-complex done up in late-Stalinist Empire health resort glory. Stage-props and simulations, eclecticism and hulking luxury calling to mind a gypsy baron aesthetic awash in gilded surfaces and stylistic interior cacophony – these are the true markers of the Mezhihirya “European Remodel”, a style which has been unceremoniously christened “Donetsk Yokeloco”.

History, it’s said, is revealed first as tragedy and then as farce. Much in the way that Viktor Yanukovych manifested blunt comic excess in his unstudied and bumbling imitation of a “true” dictator, so also Mezhihirya stands as testimony of a grotesque simulation of palatial aesthetics. It is this which has defined the approach of our architectonic concept in this exhibition. The objects removed from Mezhihirya were simply impossible to arrange into a single, unifying concept. The arbitrary nature of the assemblage, the absence of criterion for distinguishing the “authentic” from the “imitation”, the “profane” from “high art” was the result of the owner’s utter lack of even the most elemental concepts of collecting, and further, his utter indifference to the state of the arts and culture. We stood in a pile of discarded, expensive toys and came to the decision to attempt to systematize this pile, departing from any random formal categorizations, to be blunt, to form our own self-styled catalogue describing the Mezhihirya stash. We resolved to arrange the objects in such a way as that one might gather from them the general picture of the aesthetic chimera that is Mezhihirya.

And so the name “The Mezhihirya Codex” suggested itself. The roots of the word “code” or “codex” can be traced back as far as ancient Akkadian where the concept is associated with building, specifically the layered construction of stone walls. In time, the word found currency with the appearance of the first books, which, unlike the scroll, were designed as writing tablets formed of attached waxed boards stacked in layers one upon the next; these were known as “codices”. The ancient Romans attached the idea to commerce, calling their sales ledgers “codices”, and in the Middle Ages, the term applied to published chronicles of events, scholarly tracts, and law indices.

Our “Mezhihirya Codex” has provisionally been separated into “books” and “accounts”, each of which depicts a facet of the obsessive neuroses under which the ex-resident landlord suffered. The books are displayed haphazardly and yet, no matter how one might arrange them, the aesthetic absurdity of Mezhihirya still emerges from the display. What follows is our breakdown of the structural elements of this “codex”.

The Book of Time

Predictably, a dictatorship sees itself as eternal. Any absolute authority positions itself as something which has arrived for good, dreaming of historical validation of its rule, and the elimination of all unpredictable developments which might threaten it. From this arose the attendant mythologems of “the 1,000-year Reich” and “the complete and inevitable victory of Communism”. The fear of regime collapse is the greatest phobia of a dictatorship. The tyrant senses that time works actively against him, eating away at his monolithic superstructure and weakening his grip. In an evident sublimation of this phobia and apparently some unconscious desire to “privatize time”, that is, to preserve it and place it under his personal control, Viktor Yanukovych littered Mezhihirya with all manner and styles of time pieces.

The Book of Water

Water figures as a central element in any idyllic depiction of the world. Along with fire and the stars in heaven the phenomenon of water is one capable of holding our gaze without end. Water is a calming, soothing, and above all, cleansing element. In part, these explain our obsessive human urge to establish our settlements near bodies of water. The Mezhihirya residence is set on the banks of the Dnieper with yachts taking moorage on its territory. In addition to the spas and pools featured in palace interiors, water was always within sight, with scores of seascapes hung on the residence walls. The exhibition designers have arranged the paintings on a strict horizontal axis, somehow suggestive of a coherent narrative. And yet this line resembles a skewer on which has been stuck landscapes that vary widely in artistic skill, style, scale, geography, lighting, and color. Notable in this series is the Ivan Aivazovsky canvas “Feodosia on a Moonlit Night” (1875).

In this part of the exposition a number of dishes for caviar with sturgeon shaped spoons of a golden metal as well as samovars á la russe.

The Book of Light

Spatially and thematically joined to the exhibition Books of Time and Water is the Book of Light, here represented by a number of candelabras and candlesticks, made primarily of bronze, silver, and stone. Most of these objects were certainly never used by the occupant according to their primary function, thus the “Book of Light” moniker is somewhat deceptive. The candelabras were never envisioned according to their function as a source of light. In theory, they may represent the latent potential of light, but in reality, like so many other objects at Mezhihirya, they evoke some inarticulate concept of beauty, motiveless, futile, redundant.

The Book of the Spirit

In contrast to a democratic government whose legitimacy depends on the will of the people, autocratic regimes typically appeal to some sacred principle for their authority. As revealed by those closest to him, Yanukovych considered himself to be a king. His need for affirmation of the transcendent character of his personal limitless authority was intercut by the peculiar personal piety of a man “who sins, but also repents", the groundwork for which was established in the crimes of his youth. From this arises the countless assembly of icons, wildly varying in style, artistic merit, and function. Icons of a “home altar" type alongside utter kitsch, and rustic naïve forms, and massive 19th through 21st-century monastery productions stood near singular examples of Byzantine iconography, masterpieces of the Ukrainian Baroque, and rare issues of 17th-18th century provenance.

It is impossible not to recall one contemporary icon that functions as a music box and which was concealed behind a bolted, steel-reinforced door. When the door was opened a sacred hymn began to sound, without doubt a most novel approach to contemporary religious kitsch.

Set apart in this section are a few rare examples of secular treatments of religious themes, the most interesting of which represents the artist’s interpretation of a 19th-century original by Russian artist Vasily Polenov “Whoever Is Among You Without Sin” (Christ and the Woman Caught in Adultery). And yet another work which draws our attention: a psychological portrait of the personal Confessor of Yanukovych, Schema-Archimadrite Zosima.

It is here we included a number of ancient manuscripts, among which is the first Russian book ever printed – the Apostle of Ivan Fedorov, published in Lviv in 1574.

The Book of Idols

Included in the Book of Idols are idols of pagan gods and other allegorical figures. In particular we note four man-sized Italian wooden sculptures from the mid-19th century: Mercury, Athena, Diana, and Apollo. In addition to these, there are a few small pairs of 19th-century bronze and other small figures of ancient deities.

This section also includes a decorative ivory composition of heavenly gardens in Chinese hand-made Bodhisattva imitations.

Ethnographic Touches

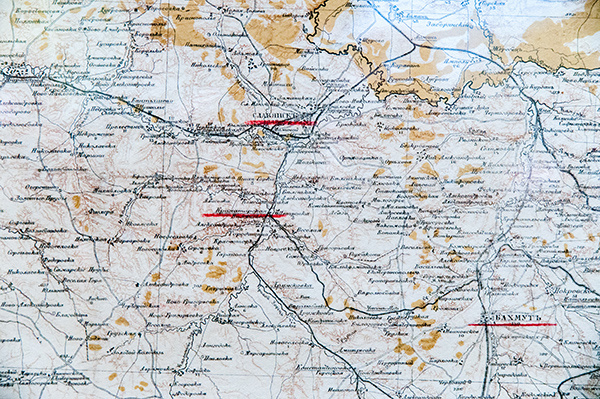

Ukraine itself held little interest for Yanukovych. In contrast to his Presidential predecessor Viktor Yuschenko, whose residences were well-supplied with ethnographic artifacts, at Mezhihirya “local art” was rather poorly represented. A few scattered exceptions to this include some painted landscapes from some rather minor representatives of the Carpathian school; a portrait of Taras Shevchenko; a modern copy of a Scythian pectoral necklace made of white metal; several antique maps on one of which modern-day Donbas has been outlined in red pencil; several antique folios of Shevchenko’s “Kobzar”, Gogol’s “Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka” and “Mirgorod” stories; as well as a large – and genuine – Trypillian pitcher, a gift, perhaps, from someone close to his Presidential predecessor who didn’t sense the impending cultural sea-change.

And yet one more pearl from this chapter – a Constructivist relief of cast aluminum of the hammer and sickle – a gift in 1932 from the workers of the Dnipropetrovsk Aluminum Plant to comrade Stalin and the OrgBuro of the Communist Party Central Committee.

The Book of Vanity

One marker inseparable from a dictatorial aesthetic is the enormous official or portrait. The walls of one room at Mezhihirya, known as “the Hall of Glory”, were hung with portrait after portrait of the former landlord.

Portrait after portrait. A most typical example of these official renderings of Mr. Yanukovych was that painted, it would seem, by the contemporary Russian artist Nikas Safronov. And yet the room contained a number of portraits with further, subtle touches encompassing the singular originality inherent in the genre. The exhibition contains one portrait of Ukraine’s fourth President done in widely popular folk cross-stitch. There is the President in amber. The President in grains of rice and other cereal grains. Chinese comrades gifted Yanukovych with a plate embossed with his image. From his Armenian friends he had a striking oil portrait of himself set against a bright orange background. One painting entitled “On the Paths of Victory!” we see Yanukovych in a helmet with a car in the background. And, as expected, no Hall of Glory can be complete absent a bronze bust of its hero.

All these works combine to give the impression of a hulking doll making a clumsy pass at an imitation of a wax figure while posing for a portrait, but which ends up best resembling a scarecrow done up in white pants, T-shirt, and gym shoes. Not less impressive is the life-size Yanukovych statuette and its bathetic monumentalist pretensions in its depiction of the man. On the pediment is inscribed the lofty pronouncement “Forward to Our Common Victory”, and below this an abbreviated quotation from his inaugural address which leaves ample room for interpretation: “Labor and achievement for my homeland.“

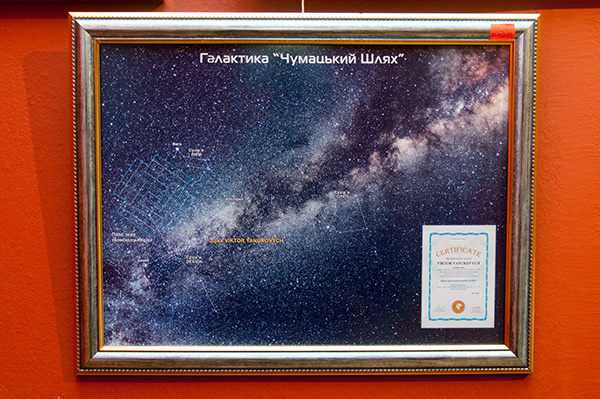

Something did not allow us to include here the “Faith, Hope, and Love” Star Certificate which was dedicated to Yanukovych, though his nearest neighbors in the celestial firmament commemorate Mahatma Gandhi, John Lennon, Kyiv artist Sergey Poyarkov, Friedrich Nietzsche, and the front man for the Russian rock group “Mummy Troll”, Il’ja Lagutenko. A separate certificate was found which identifies another star from the Milky Way Galaxy denoted unqualifiedly as “Viktor Yanukovych”.

Worth mentioning also is a two-sided engraving with gold-plate and enamel detailing which depicts Victor Yanukovych on the reverse, and interestingly, with his name included in the first seven party lists of the Party of Regions. An organic addition to this context is his collection of banknotes and coins emblazoned with the images of kings, statesmen, and presidents, and a goodly number of chalices and vases inscribed with triumphal and laudatory axioms.

Finally it is impossible to pass over a small, 60x60 painting of football player, singer, and artist Diego Maradonna entitled “Our Boys”, which he co-created on July 7th, 2013 together with the young Russian artist Yulia Kosulnikovoya while visiting the southern coast of France. Kosulnikovaya and Maradonna reproduced a photo of the Ukrainian National football team. But in the place of No. 10, Andriy Voronin, we notice a grey smudge. The portrait bears certificates authenticating Maradonna’s work on the piece. In the telling of the story of the portrait’s creation we are told “Maradonna, who has not infrequently self-identified with the Almighty, considers that a great person is indeed great in all he does”. According to the football player, by contributing to this portrait he “acknowledges the worthy successes of Ukrainian athletes in the world of sport”.

Three additional pieces from the holdings of former Chief Prosector Viktor Pshonka have also been included in this Vanity Book ensemble - paintings, all things considered, realized by a dedicated amateur. One depicts a handshake between a vassal – Pshonka – and his suzerain – Yanukovych. A second presents us with Viktor Pshonka as Commander Kutuzov at the Battle of Borodino surrounded by generals with the faces of higher ranking officers of the General Prosecutor’s office. The final portrait shows Pshonka’s wife as Russian Empress Elizabeth Petrivna. The images of Pshonka and Yanukovych had been defaced by the Self Defense troops, but that of Mrs. Pshonka was left untouched.

The Book of Stone

Stone has long held as a natural symbol of the immutable, the indestructible, as something weighty and durable in character. This section of the exhibit focuses on articles of semi-precious stone, with a particular emphasis on malachite. Yet, upon closer inspection, most of the malachite pieces turned out to be imitation, much in keeping with the overall aesthetic of Mezhihirya. As an example, consider the “malachite” desktop, which is actually a plaster cast covered in metal and then decorated in thin malachite plate.

In this section we have also placed a monumental early-20th century landscape piece by Carl Berthold – “Fjords” – depicting towering granite cliffs above the water.

The Book of Transparency

Prior to its fall, Mezhihirya was held in public perception as a mystical kingdom plucked from a charming fairy tale: an aura deriving from its utter inscrutability to profaning glances from the outside. The dictator’s residence was inherently opaque, much like the dictator’s reign. But even this opacity was superseded by the place’s sense of the utilitarian embodied in common, homely items of everyday use made of glass or crystal: vases, bowls, champagne buckets, vodka serving set, and many other types of dishes.

Representative of the spirit of this section is a tall column in yellow glass and gold-leaf on a stone base and topped with a vase. Above this splendor soars a crystal Yanukovych art deco eagle complete with a gold-leaf beak, which, when considered alongside Victor Pshonka’s eagle of semitransparent plastic, likely a cheap, and recent knockoff made in China – the latter comes off all the more humble.

The Account of the Kitchen Cupboards

In this section are included a portion of the dishes used by Victor Yanukovych, in particular, his antique tableware.

Modernity is evident here in unopened, exclusively made tableware of the top French brand Hermes, and two Lalique vases from a similar price-range.

Here exhibited is a majolica dish illustrated with Picasso’s “Three Faces”.

The Book of Chivalry

If Mezhihirya represents a presumptive facsimile of a royal palace, then its faux chivalric montage is of particular note, offering as it were, a human touch to the overall feel. Something intimate, personal, light-hearted, and refined, embodying the Yin. This imitative chivalry results from the necessity to disguise (as well as compensate for) the overt machismo of the regime, marked by the absence of any feminine character. In Yanukovych’s Ukraine, there was no actual “First Lady”. The legal wife of the fourth President resided in Donetsk and had never visited Mezhihirya, and the couple never appeared together in public during his entire term. The existence of his common-law wife was made public only after the President fled the country.

This motif of chivalry is evident primarily in statuettes of half-dressed nymphs, bathers, odalisques, classical goddesses, and vases adorned with gallants and bucolic scenery, boudoir trinkets, and 19th-century German painting, imitative of 18th-century French rococo.

It is in this section that one of the more priceless discoveries at Mezhihirya is displayed, the oil on copper treatment of “The Gathering of Manna” by celebrated 16th-17th century Dutch painter Hendrik van Balen and Jan “Velvet” Brueghel the Elder.

The true climax of the Book of Chivalry is the lightly hued print “The Peak of Beauty”, by the aforementioned Nikas Sofronov with the fawning inscription: “To Viktor Yanukovych. With respect, Nikas. May this Ukrainian girl remind us all that Ukraine is the most beautiful country on earth. Always, your Nikas. Moscow.” The authenticity of the canvas is further confirmed by the presence of the artist Sofronov’s personal seal.

In a slight stylistic departure, a modernist ceramic vase by Picasso (ca. 1950) in classical motif completes the room.

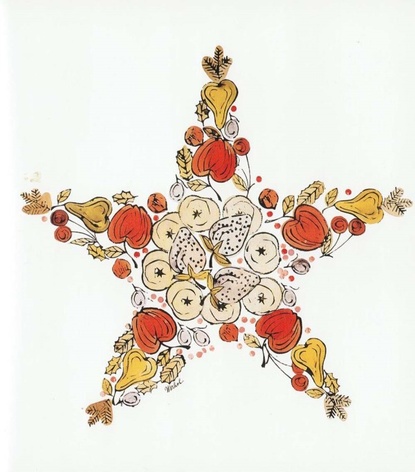

The Book of Growing Things

Mezhihirya’s owner enjoyed surrounding himself with plants of all types, with opportunity to admire them in hothouses and his main “Hideaway” (Ukr: Khonka), and in other structures on the territory. This floral motif – trees, flowers, fruit – were met in works adorning the walls of the main residence. Prominent among these were several floral still life paintings by Crimean artist Tsvetkovaya (1917-2007). This is perhaps the single contemporary artist whose work is somewhat significantly featured in this exhibit. A number of works by Tsvetkovaya had once also belonged to Viktor Pshonka.

In addition, this series includes a landscape by Petro Konchalovsky, “Maples in Abramtsevo”, from 1920, an exemplary work from one of the master’s strongest periods.

The Book of the Hunt

This common enthusiasm for the hunt which was bequeathed to the late-soviet nomenklatura by the Russian landholding class became – like much of what has become identified with Mezhihirya and its owner – a singular phenomenon in the hand of Viktor Yanukovych. The man loves to hunt. So much that even on the first night of violent police crackdowns against protestors on Maidan, Yanukovych had gone out hunting on his lands at Sukholuchia. The ex-President owned expansive personal hunting grounds complete with facilities. He kept a large collection of hunting trophies – heads and hides of all types – at these various getaways, but at Mezhihirya the theme of the hunt was held in particular esteem. Sculptures and paintings depicting hunting hounds, horses, deer, wild boars, rhinoceroses, and sketches of the hunting life are displayed in this chapter. Here one will see diplomas and certificates of accomplishment from the “Cedar Hunting Society”, crocodile hides from the Nile, the fleece of an unborn sheep, an immense and heavy silver tea service emblazoned with the heads of bison, and books distinguishing a true hunter, in particular three antique folios of the historic explorations of Mykola Kutepov dating from the early 20th century. The books, “The Grand Duchy and the Royal Hunt in Rus”, “The Hunt of the Tsars in Rus”, and “The Imperial Hunt in Rus”, the first of which was illustrated by noted artist Mykola Samokysh, were gifts.

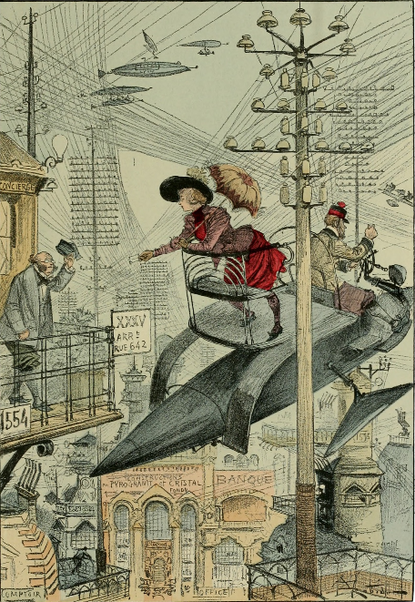

The Book of the Warrior

In this section there are very few works of art. Save a mammoth tusk engraved with a battle scene of contemporary Chinese origin, two courtly candelabras, and a 19th-century bronze pirate and gunsmith statue, this display features largely weaponry.

Boys often play at war, arming themselves with toy pistols and wooden swords. Those who continue in their fascination merely exchange their toys for the real thing.

Firearms and manual weaponry from the 17th through the 20th centuries are displayed here: sabers, swords, rapiers, yataghans, a battle-axe, a pike, a stiletto, a blunderbuss, dueling pistols, a revolver, a bayonet, a cast iron cannon and caisson, hunting and combat weapons. The curators regret their lack of expertise in this sphere, and yet there is reasonable cause to hold that this collection of weaponry encouraged a sense of fearlessness, might, and indestructibility in Yanukovych.

The Book of Conclusions

This chapter doesn’t exist except in the impressions the visitor brings away from the exhibit.

In the process of organizing this exhibit, the curators were overcome by a number of conflicting emotions. From one side there was the uneasy feeling that comes from the invasion of a stranger’s privacy. The person to whom these articles belonged, no matter what one’s opinion of him is, still lives and breathes. He continues to think about this or that, to talk about things, to busy himself with some matters, and all these things that we were attempting to understand and systematize, he still considers to be his personal property.

Yet, from the other side, a person who lives by the motto l'etat c'est moi surely has no personal life. Conclusions are to be drawn from the overthrow of a dictator. In part, aesthetic conclusions. In this instance, however, it can be difficult to distinguish the aesthetical from the ethical.

Viktor Yanukovych, who sprang from the humblest of roots, who was not well-educated, who came from the cultural margins, yet aspired to the heights of power, and once there, surrounded himself in an artificial world bedecked in artifacts proclaiming his achievement and marked, above all, by a semblance of luxury. Mezhihirya and its trappings are compelling in their statement of the obvious: that the man who appeared at an international political forum in obscenely expensive ostrich leather shoes had no inkling that his unchecked appetite for luxury was a certain, and irrefutable, indicator of bad taste.

By and large the diagnosis of “bad taste” could be readily applied to the entirety of the post-soviet Ukrainian arriviste quasi-elite. Future politicians must be made aware of one simple matter: bad taste is unacceptable. The preponderance of outrageously expensive cars in a country where the majority live below the poverty level is unacceptable. Public officials of a county who are busy organizing junkets for themselves while the public health and education systems are in freefall evince the height of cynicism and indecency. It is unacceptable that the barely literate who have managed to make their way into power continue to surround themselves with expensive toys while the nation’s remaining, and authentic, elite – its thinkers, cultural activists, scholars, and educators – are regarded as dispensable or paid wages below those offered for unskilled labor. It is unacceptable that while the chateaus of government attorneys, prosecutors, and parliamentary deputies overflow with pricey and often absurd “antiques”, there have been – in the 23-year existence of this European country of 45 million – no systemic acquisitions for State Museums.

It is unacceptable that the role of culture in society has been reduced to servicing the undiscerning demands of an unsophisticated elite, though it ought rightly hold its place as the center piece of national security strategy.

It is told that shortly following the War a directive was adopted prohibiting the display of realistic painting in government institutions. At first glance this seems a most undemocratic and ridiculous measure, yet its result was that it allowed contemporary art to make its way into the halls, and onto the walls, of power. In time it began to mold the official State aesthetic. In place of massive, carved and gilded tables and chairs, offices were equipped with modern furniture of simple, and practical design. Take a look at photos of the interior design of the office of the current German Chancellor. In a working space laid out in this manner, even the highest placed official stands little chance of ever adopting lordly attitudes.

The tendency toward both ostentatious luxury and chaos inhabit the same space – between the ears. If our ruling class would reject the urge, if it would demonstrate good taste and a sense of cultured restraint, its needs reflecting something more authentic than the urge to always put on airs, then, it is likely that Ukraine would rid itself of its wild corruption and unconscionable theft. Leading, perhaps, to a change in the nature of power here. In a normally functioning society, power is not a source of unregulated personal enrichment, but a service, accountable to a country and its people. It is in the hope of that type of society that Ukrainians filled Maidan, and for which they died there.

Glory to Ukraine!

Alisa Lozhkina

Alexander Roytburd