Moscow Curatorial Summer School 2012: Doing Exhibitions Politically

My experience of the Moscow Curatorial Summer School was marked by a sense of urgency from the moment I read the announcement that the V–A–C Foundation in partnership with the Russian State University for the Humanities was launching the first MCSS, that it would be directed by Viktor Misiano–a curator's whose work strongly resonates with me, that it had a concept–"Doing Exhibitions Politically." I filled with a strong desire to be in Moscow in the company of the invited teachers (theorists, curators, artists from all over the world) and whatever other students shared my concern for the School's theme for three weeks in July. And once I arrived, in the midst of continuous intellectual, communicative and aesthetic activity, the sense of urgency persisted. It was a feeling that one has to do something in that moment, but you yourself are responsible for deciding/discovering/desiring what exactly it is that you have to do.

The School itself was organized like a curatorial project, and everything that we did directly or indirectly steered the students to engage in "curatorial thinking." The MCSS offered a wealth of information and opportunities – potential colleagues in the participants; older, wiser mentor-experts in the invited lecturers; additional events like artist talks, film screenings, exhibition openings to watch, reflect on and talk about – and we, the students, were invited (or obliged) to absorb and engage it as we desired. Working within our own limitations (skills, knowledge, time, etc.) – in other words, reality – we had to constantly decide where to direct our attention, when to make greater efforts and when to let things go, continually negotiating our own way through the available resources. Visiting lecturer Reesa Greenberg, a theorist and researcher of exhibition practice, likened the MCSS to what she terms an "aggregate exhibition" – a project composed of many different parts that come together to form something more than a whole, something that is impossible to experience in its entirety due to its scale and the limitations of any one human viewing subject.

Each participant had a strong and specific personal relationship to the concept of "Doing exhibitions politically," and communication happened through these individual positions. The emphasis shifted from who we are to our relationships with the material (concepts, artworks, ideas, tasks) we were dealing with. We talked about the current state of the art world, institutions in crisis, the powerful influence of the art market, turbulent art activism all over the world, the interrelations of art and politics. The MCSS was not oriented toward production and a clear sympathy for leftist political thinking (sometimes subtle, sometimes direct) reverberated through the lectures and presentations. While I am not a champion of neoliberal capitalism, I was perplexed as to why our discussions with experimental artists and thinkers continually accepted economics as the primary force that organizes our world and artistic practice.

Somewhere amidst all these relations between thinking subjects and artistic/intellectual material, I began to sense another emotion – love. Neither interpersonal, nor resembling the collective ecstasy that builds around mass demonstrations and football matches, this love was something connecting all the MCSS participants, and parts of the world around us, generated by our common efforts to continually think and articulate our own positions in relation to the ideas we were engaged with. Perhaps this love was a by-product of the particular nature (and geographical situation) of this year's MCSS, but it is a strong potential alternative way of relating to others (people, objects, ideas) that is not dependent on identity or economic exchange.

I believe that curatorship today involves creating conditions for relations. How can a curator provide a platform for diverse voices in a way that honors the integrity and authenticity of each voice and displays its relevance? What elements or approaches can allow other ideas/emotions/events to arise (perhaps unexpectedly)? After three weeks discussing the institutionalized art system at the MCSS, I realized that such "professional" curatorship is not for me. And yet, this only heightens my determination to continue organizing people, ideas, artworks and asking questions in pursuit of discovering what exactly it is that I, as a curator today, have to do.

Comments from Students:

Elena Yushina (Russia):

In today's circumstances in Russia, such educational initiatives provide an opportunity to take a super-intensive course in a short period of time, that opens an immense field of educational and research material, and also helps young curators gain confidence in their own skills, engage with trends in the international art community, familiarize themselves with its leading representatives and subsequently become leaders of Russian contemporary art on the world art scene.

This unprecedented event coincided with my inner mindset of searching, analysis and experience. "Position" and "situation" for some time became the most frequently used words… which is not surprising in the "situation" of permanent critique of the institutional system, including the contemporary art system. The search for an artistic gesture done "politically" and the analysis of references to large exhibition projects went on in such a pleasant and friendly atmosphere that it was impossible to refrain from asking: is contemporary art about "friendship" (V.Misiano) or, nevertheless, about "love" (P.Gielen)?

Corina L. Apostol (USA/Romania):

I think the program organizers did a great job of not only giving us access to important events (such as the Biennale for Young Artists or the screenings of "Za Marksa" by Svetlana Baskova and "Russian Woods" by Chto Delat?) but also linked us with local activists, artists and curators. ...I thought the quality of the seminars and presentations was very good and especially that we had one-on-one discussions with our lecturers outside of classes. . . . As for "doing exhibitions politically," this experience formed my opinion (as a writer/curator who works internationally) that any political gesture has to be informed by a thorough knowledge of the local context and the specific history of the place in which we are working. Without this insider knowledge and the solidarity of local artists, activists, writers, curators one can hardly develop a responsible and effective curatorial strategy in a foreign context.

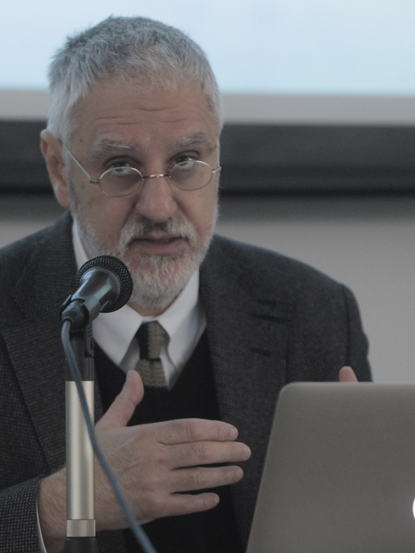

Comments from Viktor Misiano, Director and concept author of the MCSS

Please describe the thinking process that motivated your decision to organize the MCSS in this particular way and around the concept of "Doing exhibitions politically". Why were you interested in providing maximum material for absorption/reflection/discussion and minimal demands for the students to produce anything?

Summer school differs from regular school in its lower degree of obligation. The university routine may seem tedious and pointless, but there are still plenty of reasons for the student to endure it and eventually receive a diploma. Summer school will only gather students if it involves an element of intrigue and temptation. In addition, even though contemporary knowledge has abandoned its claims to universality, university studies are still structured around a sweeping and comprehensive narrative. There is simply no time for that in summer school: its object should be more focused - one theme, one subject. In other words, a summer school should be structured like an event, devoted to one highly relevant topic that arouses great interest.

I think at that particular moment, spring-summer 2012, there was no alternative to the theme "Doing Exhibitions Politically" (in some formulation or other). The mass protests against the falsified elections seriously stirred up the urban class, especially the younger generation, and highlighted the relevance of the problematics of art's civic engagement. Also, by the beginning of the 2010s, the discussion around art and politics had acquired a lot of material: it was transforming from urgency into a new tradition, i.e., it had reached the stage where – without losing its edge – it had adopted an academic character; in other words, the moment had come to shift it into the educational system.

As for the school's inclination toward theory rather than practice, to a large extent this came from the students' self-organization and the curatorial group WHW, who was responsible for the school's curatorial workshop. Upon opening the school, I stipulated that the students decide what form their final project will take. Undoubtedly, we could have found an exhibition space for their project, which would have displayed the result of their collective efforts. But I think that the projects ended up being for the most part virtual for reasons not only subjective but also objective. For a group of around twenty rather inexperienced people who don't know one another to make a comprehensive exhibition project together in three weeks is a difficult task, in fact, hardly feasible…

However, there is another, more methodological reason for wagering on theory rather than practice. The main problem with contemporary curatorship in Russia, as well as in many other post-Soviet countries, is not a lack of practice (which, of course, is also present), but that the display of art in exhibitions is not embedded in discourse. In fact, the prevailing conception does not presume such correspondence at all: art and its representation are not thought of as part of intellectual discussion and research. So that is the particular lacuna that we wanted to fill, inasmuch as is possible in three weeks, and with maximum intensity.

Please describe any significant differences between your expectations for the MCSS and how it turned out.

The experience of directing the school did not leave me with any traumatic disappointments. Certainly, if I end up running the school again next summer, then I will critically consider this experience and make some adjustments to the organizing principles. First, I will monitor the students' actual knowledge of English more carefully, since the lack of English speaking skills was a serious problem for many during the working process, a large portion of which went on in this "lingua franca."

What is the work of a curator today?

My friend and colleague Bart de Baere titled one of his now-canonical projects "This is the Show and the Show is Many Things." I think what is most important is that curating is a practice determined by each person who devotes him/herself to it. For me, personally, today it is also a didactic project. Indeed, the school demanded the effort of a project: the team of teachers, course topics, the rhythm of its development, the mix of theory and history, of doctrine and entertainment - all this was filtered by me. Thus the subsequent school will be different – in contrast to the school routine, the school-as-project cannot repeat itself. The next school will be a different project…

Larissa Babij