Serhiy Hai and the Art of the Beautiful

Beauty lies in the eye of the beholder. A commonplace and charmingly dated phrase; still, it is precisely what Serhiy Hai presses upon his audience to consider. The Lviv-based artist’s current exhibition of twenty-eight paintings and twelve mixed-media drawings on view at The Ukrainian Institute of America (New York), are willfully labeled Untitled, the painter conceding responsibility to the onlooker for judgement and comprehensive experience1. However, the artist mustn’t cut loose of the activity at just that point. After all, a mutual, if not contractual responsibility, resides on both sides of the aisle of artistic creation and absorption.

Works of art are made; they do not simply spring into existence as objects freely available for personal interpretation. Intelligible aesthetic judgments must take into account the point of view of the artist, first, then the spectator. They are intentional creations, using the historical traditions, conventions and resources of the artist’s practices which ultimately afford them meaning and life. Certainly, the validity of the “beholder” statement has been discussed and argued ad nauseam; the connection is purely subjective. That is to say, whereas terms like black and white, smooth and rough, hot and cold identify real properties of an object—an original artwork—the term “beautiful” says something about the person who uses it. This is the view embodied in the expression above.

Simply put, it is true that works of art can give pleasure (from beauty) and can be valued precisely because they give pleasure. However, to value them solely for this reason is to give art no special status over other sources of pleasure. The Kantian2 abstract, as witnessed here—appropriately, if not expediently applied to Hai’s exhibited intention(s)—is an advance on aesthetic hedonism. By taking beauty as its focal point, it identifies a pleasurable experience that seems to have some special relation to art, and with Hai, advances a further universal character and experience than simple personal desire and satisfaction. As an artist ingrained in the modern tradition, he comes away from his ideal representations of preferred classical motifs with a determined understanding and humanistic emotional encounter, on par with history and philosophy. Certainly—with this writer included—there is pleasure to be gained from viewing his paintings and beauty to be found in them, as they are often moving, but these basic features alone cannot explain the works’ value at their finest. Moreover, modern sociological alternatives to weighing in on Hai’s classicism do not enter the fold, in this instance. Nor can they be properly accommodated within that context, given his traditional and emotional approach to art making in and around the historically and culturally fabled surroundings of his beloved Lviv. Rather, Hai continually seeks for a way to understand the ideals that shape his own presence in terms of historical, emotional and cognitive functions his motifs play, and not by tracing the changes in their function through history.

Therefore, the concept of the “beholder” is a subjective detriment, an obstacle, to the classical concept of beauty, which would seem to hold true over time. Those who live by that phrase, those who profit from it, and those who accept it, either have an agenda or are being very short-sighted about beauty. Beauty lies in the object itself, and, through working and reworking his classicist motifs, the mature Hai helps propel and discern it. The beauty exists in of itself, whether there is the artist who sees it or the beholder who, at first, is immanently blind to it.

It makes sense, then, to speak of a return to beauty in recent art making practice; allusion to the past, and particularly to the past of antiquity, has been crucial to much of the art called postmodern. But, there is danger, here, of reinforcing the perception that beauty is a thing of the past, and that an art that aspires to beauty must therefore be nostalgic, if not reactionary. Thus, an opposition to the anti-aesthetic runs the risk of resigning to the terms of that rhetoric. To resist any kind of art authoritarian progressivism the only course could be retrogression. Herein emerges Hai.

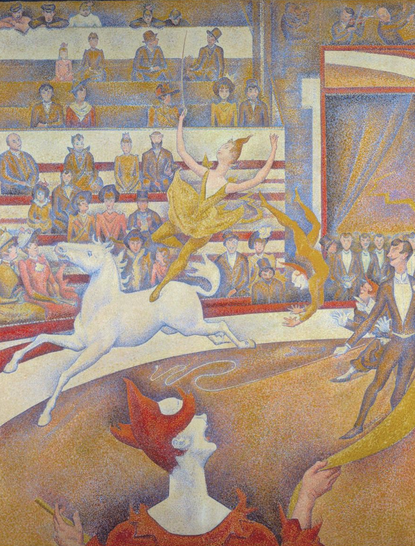

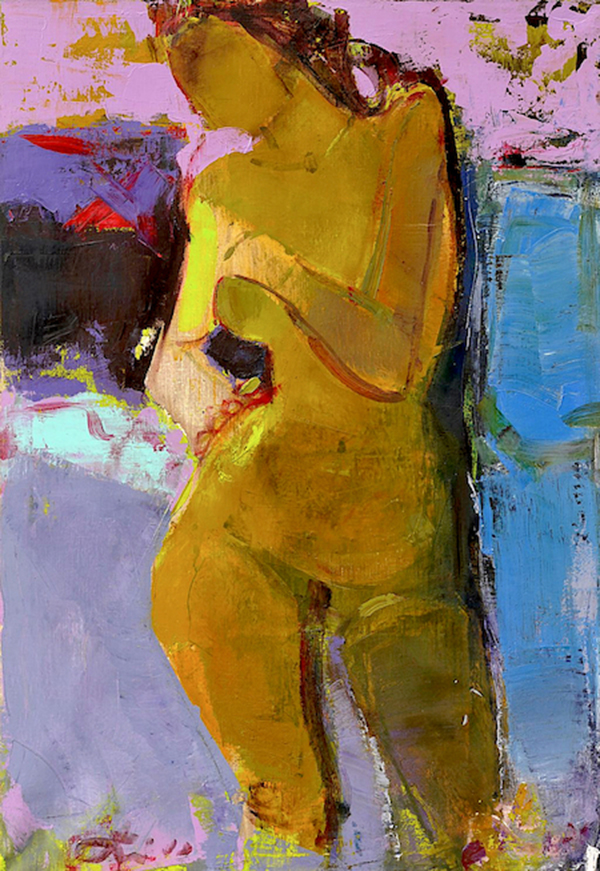

The current exhibition realizes four distinct groups of paintings by Serhiy Hai featuring iconic motifs traditional to the canon of Western art: riders and horses, nudes, masks, and still lifes—themes the artist has explored comprehensively throughout his prolific career. To be sure, the ideals represented are not motifs, as such—they are the medium for colors and forms that evoke the realities of infinite psychic depth, physical observation and associations with distant archaic ages.

The archaic in Hai—his relationship to Etruscan art and culture—is not exclusively a decorative-historic reexamination of that era. Rather, it testifies to the simpler array of colors, tones, and forms that originate with the distant archaic. Hai frees himself from every form of strict academicism and Hellenism in order to carry on, with a contemporary sensibility, that early classic Greek tradition. There exists an inner connection between his chosen motifs—partly understood as symbols of a lost humanity (unidentifiable visages entertained as archetype), partly as symbols of the mysteries of life on earth—and the forms that transmit them to us purely and freely on the aesthetic.

To be clear, Hai is inherently a formalist through and through, with a nod to the School of Paris clearly playing on his pictorial affections. His process goes from inside to out, and the techniques of applied line, color, and form are the central components with which he works. This trinity would be nothing but pure abstraction were the perceived symbolic motifs not wholly incorporated in it.

Following this formal course, Hai’s paintings are as much about surface and process as they are about their perceived subjects. The subject, or content, is bound up inextricably with form and form is essentially pointed to and described in the individual motifs, here. Hai consciously uses the formal devices at his disposal to call attention to aestheticism, and not issues, per se. The limitations that constitute the medium and practice of painting—flat surface, shape of support, properties of pigment, color and line—are, for the artist, to be regarded as positive factors.

A proprietary application of aqueous oil and acrylic mediums affords the pigments to commingle in thin translucencies—sunken hues and values rise to the top as if from deep below the skin and surface. Hai subjects the effects of light and color to the form in such a way that the latter receives absolute significance—credible and self-absorbing. His brush seeks surfaces in order to feel them, caress them, and fondle them—this is a sensual and romantic refinement to his extension, and is also a means by which he awakens the notion of the beautiful from the depths of his inspiration. This is how Hai surrenders to the visual splendor he makes and loves with such abandon. It lingers with him in the magic of residing silently in his Lviv studio, practicing his craft in relative isolation.

As his painting has developed over the years, Hai’s sensibilities related directly to artists in Modernism’s past, whose works were also somewhat difficult to encapsulate into a movement, Vasyl Khmeliuk and Marino Marini, in particular, whom he figures. Were it at all possible to balance on the point between the construction and deconstruction of the figure, these two prove to be models of capricious art practice that have understood the precarious nature of figuration in the 20th century, albeit from culturally different yet parallel points of pictorial and historical reference. The calculated distortions and deconstruction these artists have engaged in their paintings (although a prolific painter and printmaker, Marini is known mostly for his work as a sculptor) are inseparable from what could be called their realism. It is a realism where painting seems as if it has been put to the service of seeing and depicting in their primal rather than most derivative sense. The figure, even when it is being carefully considered, is formed around different types of sheer instabilities and dislocations.

Like so many of Hai’s paintings, his representations combine the real with the imagined, and the imagined with the real. The motivation for painting is sober. His eyes do not roam indiscriminately, but evaluate and reevaluate the sensual notion of figure, man and beast, and nature morte that reflects the mysterious complexities of his description. The foundation of old-fashioned Modern representational painting boils down to an understanding that flux and instability are at the center of the artist’s and, ultimately, the viewer’s impression and awareness.

One wants to describe the paintings in this exhibition as emotional artworks, but the gestures are not fully expressionistic as they are finely and deliberately stroked. Serhiy Hai tracks down, resolutely and with talent a hidden secret between the viewer and the objects of his affection, between the joys of seeing, the meanderings of imagination, and those of memory.

Serhiy Hai was born in Lviv, Ukraine. In 1986, he graduated from the Lviv State Institute of Applied and Decorative Art. Since 1995, he has been a member of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine and has participated in exhibitions throughout Ukraine, Austria, Denmark, England, Germany, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Switzerland, and the United States. He lives and works in Lviv.

Serhiy Hai: Painting, curated by Walter Hoydysh, PhD, opened on October 14 and runs through December 11 at The Ukrainian Institute of America, 2 East 79thStreet in New York. For further information, please call Olena Sidlovych, executive director, at (212) 288-8660 or mail@ukrainianinstitute.org.

Celebrating its sixty-second year, Art at the Institute is the visual arts programming division of The Ukrainian Institute of America. Since its establishment in 1955, Art at the Institute organizes projects and exhibitions with the aim of providing post-war and contemporary Ukrainian artists a platform for their creative output, presenting it to the broader public on New York’s Museum Mile. These heritage projects have included numerous exhibitions of traditional and contemporary art, and topical stagings that have become well-received landmark events.

Notes

1. Conversation via Skype with the artist and Walter Hoydysh, director of Art at the Institute.

2. Immanuel Kant was an influential 18th century German philosopher whose studies initiated dramatic changes in the fields of epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. His theories came to be known as critical or transcendental philosophy. Of particular importance were the so-called three Critiques: theCritique of Pure Reason, Critique of Practical Reason, and the Critique of Judgment. Modern aesthetic thought began with Kant, but divided into formalist and sociological camps in the decades and centuries to come.

©2016 Andrew Horodysky. All rights reserved.

Images attached:

1. Serhiy Hai, “Untitled” (Horse and Rider), 2016, oil and acrylic on canvas, 51 x 67 inches.

2. Serhiy Hai, “Untitled” (Nude), 2011, oil and acrylic on canvas, 51 x 35.5 inches.

3. Serhiy Hai, “Untitled” (Still life), 2015, oil and acrylic on canvas, 35.5 x 47 inches.