Vyshy-wow! Ukrainian embroidery in contemporary art

The cultural context of Ukrainian decorative art is an enduring issue. Throughout the 20 years of our independence there’s been a tireless reiteration that the quintessential Ukrainian art form consist of the pysanka (painted egg – ed.) and the vyshyvanka (traditional embroidery – ed.). There’s nothing wrong with preserving this cultural heritage by building new museums, publishing books and promoting government support. Yet, supporters of a diametrically opposite cultural position are unwittingly labelled ‘dissidents against culture’, and opponents are named ‘obscurants’ and ‘ethno-centralists’. In doing so all elements of folk art are reduced to one scornful term – ‘sharovarschyna’ (a reference to wearing traditional Cossak-style trousers – ed.).

However, if you move beyond this thematic conflict and instead consider what has already arisen within the world’s artistic processes, we can conclude that the dialogue between these two irreconcilable discourses, that is, between ‘decorative’ and ‘contemporary’ art, has already been at dispute for a long time. Today the line between these positions appears so blurred, that instead of ‘decorative-applied art’, it’s perhaps time to talk about the ‘contemporary decorative’.

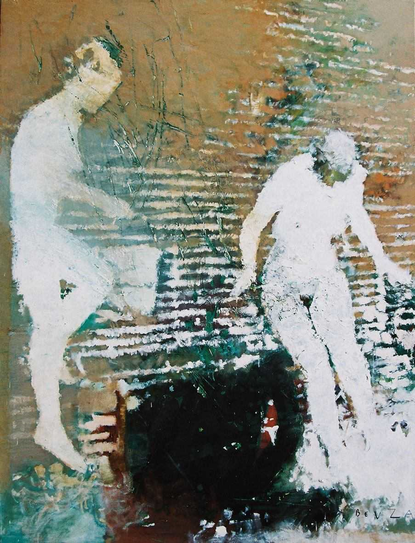

Photo: From the collection X'U/KUZNETSOV 'Conspiracy'

At the end of this first decade of the 21st century the world art community has started to pay more attention to handcraft, including the entire sphere of contemporary textiles, and especially embroidery. Handmade needlework, weaving, and gold or silver-threaded embroidery, are gradually departing decorative-applied art museum storerooms, and are claiming their rightful place as a significant art trend. In 2007 The Museum of Arts and Design in New York held a major exhibition entitled Pricked: Extreme Embroidery. It aimed to rehabilitate the still marginalised genre of ‘hand work’, and heighten the regard for these 21st century art as self-contained art objects.

Photo: From the collection X'U/KUZNETSOV 'Conspiracy'

In 2009 the Centre Georges Pompidous in Paris followed New York’s initiative by conducting a revolutionary review of its own museum collection, starting with a long-term project code-named Elles@Pompidou. Its worth considering that the essence of this project is to create decent alternatives to ‘masculine’ art histories. The French curators decided to ‘evict’ all works by male artists for a number of years. In the new version of the permanent museum collection, its entire 40 000 square metre exhibition space has been filled exclusively with ‘women’s’ art. The contemporary sewing section has selectively highlighted an area called A Space Sewn Together. It takes almost an entire floor, and includes, among lesser-known artists, works by Frida Kahlo, Annette Messager and Louise Bourgeois. But is contemporary art’s current interest in technical textile work altogether new?

Photo: From the collection X'U/KUZNETSOV 'Conspiracy'

…And again, the sun warms the blood-reds of painters (M. Semenko)

Thinking historically, this isn’t the first time the avant-garde has returned to textiles. Throughout the 20th century there were at least two attempts to modernise this artistic genre: first, in the wake of a great revolution in imagery between 1910-1920, which mostly transpired within our country’s bounds, and second, in the second half of the century on the other side of the Atlantic, as a result of radical feminist critiques of contemporary culture.

Sonya Clark. Afro Abe II. 2007

Hand-embroidered French knot on a US$5 banknote

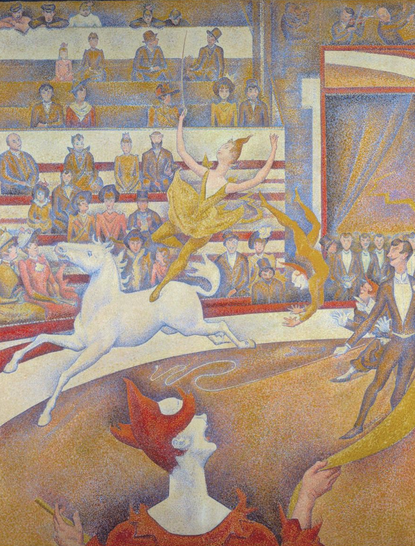

Despite their great diversity, avant-garde trends at the beginning of the 20th century had one thing in common, or rather, a common utopia – the possibility of total artistic revolution and establishing a regime of boundless creativity, devoid of class or gender hierarchy. And they also had common enemies - bourgeois taste, the embodiment of elitist and limited artistic salons of the 19th century. Naturally, by trying to overcome the limits which had been imposed upon them, artists turned towards folk art motifs, a priori anti-intellectual, sometimes kitsch, and highlighting the poor and even exclusively-known ‘women’s art’, which had been gathering dust for centuries in village chests.

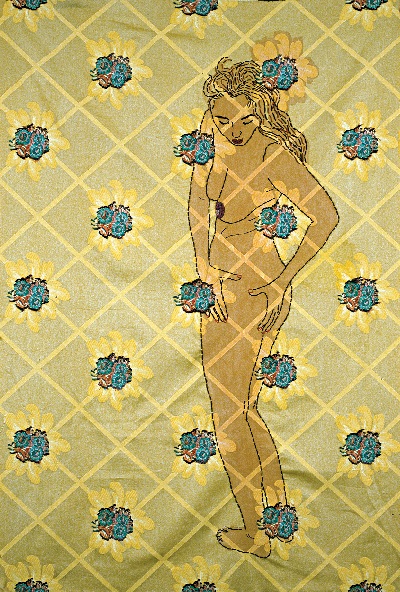

Orly Cogan. Woman. Hand-emboidery on silk

Critical curatorial writing about these themes has only recently commenced. In 2009, the Proun Gallery in the Moscow Winzavod complex held an exhibition called Manual Labour. Handicrafts. which engaged with avant-garde textiles. And in February 2010 in Kyiv there was an exhibition, Updated Masterpieces, in which designs by Kasimir Malevich, Alexander Exeter, Hanna Sobachko and Vasyl Krychevsky were sewn using modern embroidery.

Skart. New embroidery (2000's — present)

I embroider golden threads into the kerchief, I bestow, and it kisses me (T. Shevchenko)

In his ‘Introduction to Psychoanalysis’ in 1900, Freud argued that the only cultural heritage which civilisation owes women is the invention of weaving and braiding. He justified his opinion by arguing that the main impetus for his position resulted from observation of a woman’s pubic hair and the way she suffers from a lack of phallus. He proposed that this was compensated by “masturbatory movements in the work of the spindle.”

Fortunately, these ideas may nowadays just raise a smile, but we can pay tribute to Freud in the sense that this reflection was the first articulation of centuries of phallic hierarchy in art, where men, and only men, took on the role of creator, and women were relegated to a secondary role as dutiful worker. Incidentally, American contemporary artist Elaine Reichek in her Samples series perpetuates Freud’s famous lines by embroidering them in a retaliatory action as a cross on a white background.

French-American artist Louise Bourgeois has her own interpretation of Freud. Her first few metal sculptures present images of needles and a spindle as a complex metaphor of the phallus (the elongated form) and the female (the needle’s eye). In her later sculpture, Heart, she uses the threads from a weaving spool, and connects them to a realistic model of a heart muscle. Bourgeois eventually affirms her attitude to weaving in a major metal web-like work, which the artist associates with her mother. Bourgeois’ mother was a professional tapestry restorer. On one hand, she encouraged her daughter to pursue art, and on the other, imposed a symbolic ban on the process of weaving: ‘my children will never pick up a needle’. However, in the last stage of her work, Bourgeois, in accordance with generic conventions, upsets her mother’s ban and begins to work closely with textiles. One of the most famous works from this series, Ode to Oblivion (1993), is a book embroidered with scarlet threads which depict childhood memories.

Niki de Saint Fall. The Bride and Eva-Maria. 1963

Netting, plaster, lace, assorted painted toys

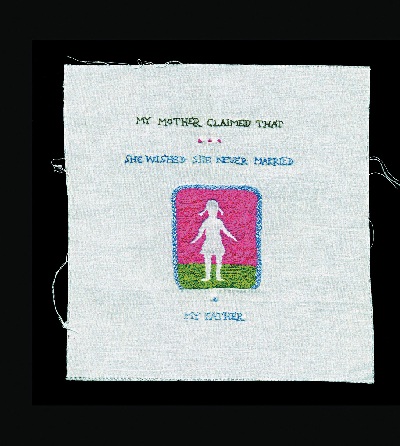

Embroidery, as a metaphor of motherhood and desolate childhood paradise, can also be located within the works of other artists. In her series of works entitled MOM, a young American artist with Korean background, Jung Eun Park, clearly articulates her appeal to mothers. Like Bourgeois, she embroiders texts using scarlet threads on a white background. US-Romanian artist, Andrea Dezso, born in 1968, enters into an ironic dialogue with her mother, especially concerning her Romanian village origins. She produced a series called Lessons From My Mother, ironically quoting prejudices and parental tips on sexuality: “If you let a man fuck you, he’ll leave you because every man wants to marry a virgin.”

Witches! Witches! Don’t stand near and don’t gaze upon my cows! (Invocation)

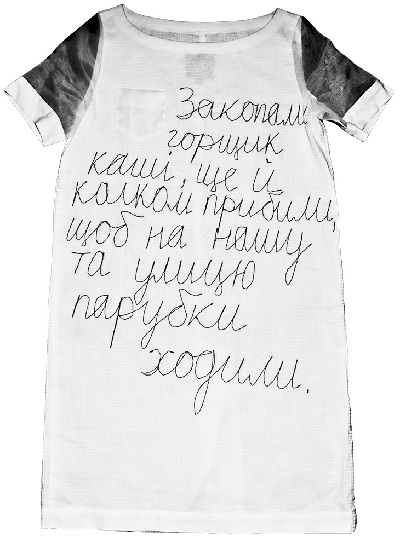

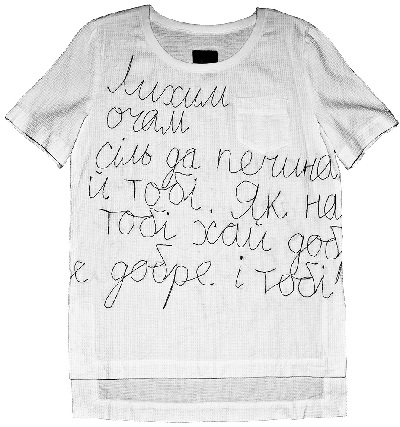

Ukrainian artist Volodymyr Kuznetsov works with similar textile techniques. He recently presented a project called Conspiracy, a collaborative work with a young fashion designer, Ksenya Marchenko. The project is a collection of white dresses and shirts which were manually embroidered with ancient Ukrainian invocations. The artist uses direct oral quotations from Ukrainian folk art, in contrast to his own prosaic poetry which was presented in an exhibition of finalists for the PinchukArtCentre prize in autumn 2009. In this series the artist takes a decisive step towards decorative art, actualising the process of creating Ukrainian embroidery. Because embroidery has a deeply profound appellative function, rather than simply decorative, it can be considered akin to poetry, and the writing process more generally. There is a hint towards this affinity in their common linguistic root - ‘text’ and ‘textiles’. Text is not unlike wicker, a materialization of embroidered signs and symbols which convey a coded message.

Shizuko Kimura. Models in New York. 2006

Hand-embroidery on cotton, silk and synthetic thread on muslin

Giotta Moore expresses this sentiment from the depths needlework boxes in an intimate female space: ‘I’m scared to death’, ‘This is fucking bullshit’, ‘I love you so much it scares me’. Her frank confessions are presented in the form of a private journal. She presents flowery handkerchiefs in the background, stretched across an embroidery tabouret. Israeli artist Dafna Kaffeman also makes a background using handkerchiefs, although with less tentative political slogans. Arabic Is Not Spoken Here unequivocally declares her political embroidery, raising the question of the Arab-Israeli conflict, albeit in a linguistic plane.

A message with a slightly different nature, but also drawing upon connotations of war and death, is expressed by British artist Paddy Hartley. He uses a First World War military jacket to investigate an as yet unexplored genre of textile sculpture. Recalling the horrors of war in his technique, which are indeed difficult to consider ‘feminine’, the artist attempts to unite textile tradition with contemporary computer technologies.

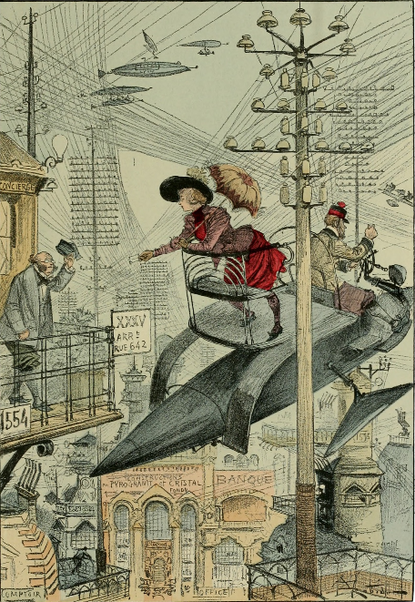

French artist Virginie Rochetti also makes use of ‘computerised’ embroidery, creating a modern equivalent to the medieval Bayeux tapestry (11th century). In this large-scale work, reaching 60 metres in length, Rochetti traces the history of today as seen on television screens, thereby creating not just a daily journal, but an embroidered chronicle of modern history.

Adrea Dezso. She Never Wanted To Marry from the series Lessons From My Mother 2005-2006

Hand-embroidery using silk threads on silk fabric

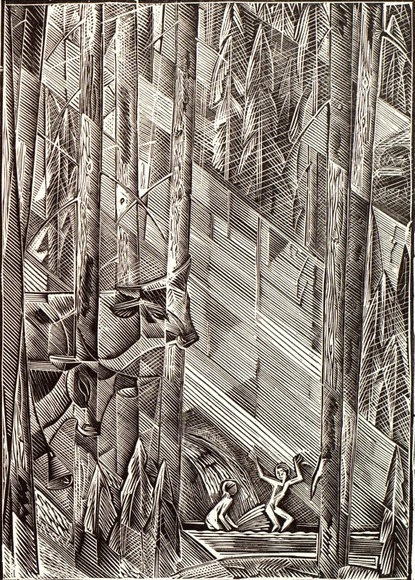

The embroidery process has even been depicted in video art. Mexican Ana de la Cueva uses a sewing machine to methodically map the US-Mexican border. The mechanical movements of the needle show how it will become increasingly difficult for ‘aliens’ to cross the border. Bosnian Maia Bayevic’s performance is unforgettable. She invited five women refugees to embroider patterns, for five consecutive days, on netting which was covering the bombed National Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo. Video documentation of the performance is screened at the Centre Georges Pompidou.

Karen Birch. Broken Time. 2005

Hand-embroidery using silk threads, hand and machine painted manually sewn acrylic balls

So now, just as it was hundreds of years ago, embroidery is the language of art. A somewhat archaic language, and perhaps not as ‘grammatical’ in structure as contemporary media audiences are accustomed to. But it’s still very symbolic and rich with new metaphors. It’s worthwhile just to listen, and find that embroidery can speak about more than ‘red and black’, the traditional colours of Ukrainian embroidery - where red refers to love, and black to sorrow. It can also speak about pressing contemporary topics, like gender identification, social inequality, violence and war.