incertae sedis. Heather Dewey-Hagborg: The Portrait of Your Chewing Gum

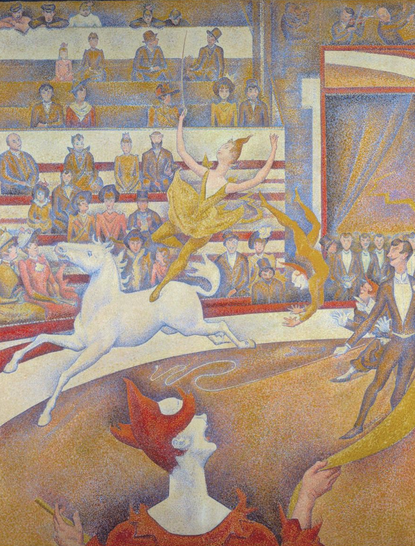

Once seduced by early cinema, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque invented a new approach to portraying people. It took art historians almost a hundred years to figure out that the founders of Cubism were primarily inspired by pioneering motion pictures, working in the epoch of mechanical modernism of Lumiere brothers and crazy infant experiments by George Mêliés.

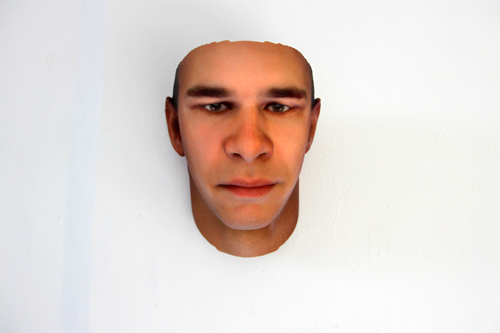

Another innovative approach portrait – the art-identikit of the 21st century – was invented by Brooklyn-based artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg who adjusted DNA-analysis and 3D-printing technique; and deserves to be an original art form in new media arts arsenal. She started collecting hairs, cigarettes, chewing gums left around the city and learned how to test the strangers’ DNA. Unlike Picasso’s or Braque’s cubism paintings, her masks of unfamiliar persons are also fractured but from the phenotyping perspective. Those reveal such fragments of information as sex, eye color, ethnicity of the individual but not precise facial features because the technique is still new. Similarly to cubist paintings, Dewey-Hagborg’s artifacts strive to investigate multiple perspectives on an object – but from the moral and ethical viewpoint, first of all. The author of “Stranger Visions” project called attention to the potential for a culture of genetic surveillance much earlier than the Ukrainian Department of Interior had announced the initiative of creating a national DNA database in a bid to help track and fight crime in the country.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg has a BA in Information Arts from Bennington College and a Masters degree from the Interactive Telecommunications Program at Tisch School of the Arts, New York University. She is currently a PhD student in Electronic Arts at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Heather has shown work at PS1 Moma, the New Museum, Eyebeam, Clocktower Gallery, 92Y Tribeca, Issue Project Room, and Splatterpool in New York City, the Poland Mediations Bienniale, Jaaga art and technology center in Bangalore, and the Monitor Digital Festival in Guadalajara and many more.

And she is my second heroine in the INCERTAE SEDIS column dedicated to hybrid arts that are being born on the edge of contemporary science, art and technology.

Lilia Kudelia The idea of DNA as a clue seems to be thrilling to me since my friend told about his experience working as a camera man at the White House. The main intrigue of my friend’s story was about him biting his nails while he had an anxiety attack. “A part of me is still there in my DNA”, he said. As a society, we are already aware of the many ways we unintentionally ‘publish’ our personal information in civic space. However, as an artist you not only look at this as genetic material but also as the evidence for genetic surveillance. Based on your experience working on the “Stranger Visions” project, what are the most disturbing bioethics issues in your work?

Heather Dewey-Hagborg There are so many of them, and they are so complex and entwined. First of all, there is the surveillance aspect. That is what initially attracted me into this project, because I used to work with surveillance and various capacities before. There are so many ways that we are surveyed in our contemporary sphere. And the issue of genetic surveillance is a little bit new. We don’t tend to think about it as consciously as we think, for example, about our Internet browsing history. It will be really becoming much the same. So this is a definite concern for us to think about.

Secondly, if you can tell someone how they can look like, then you have dilemmas that come up with pregnancy, for example. This is a major area of bioethical issues. If you can generate a picture of how your baby would look like, then there is a whole dynamic of mother’s choices in “designing her baby”. These are two the big problems.

The other question related to this project is more conceptual and theoretical, which is quite an exploration for me right now. This gets to the history of genetics and our tendency to racialise technologies. I am wondering about eugenics movement, and how enormous it was, and how much it dominated scientific research in the late 20th - early 21th century. That is something I think we need to be more aware of.

- Speak to us about the process of your work on Stranger Visions project. The most difficult phase seems to be about extracting the DNA information from the clues that you find. Do you work with scientists? And how does this collaboration with researchers happens?

- For me, the big challenge of this project was the biological portion, because I didn’t have a background in lab biology. Therefore I signed up to take a class in a local community technology lab in Brooklyn called Genspace. They told me how to take the DNA, how to amplify and look into it. I took that as a starting point and continued working with a biologist in that lab. I am also working on my PhD project at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, so I started collaboration for “Stranger Visions” with a professor here. I have had a lot of help from people who know more about these things than I do to help guide me and point me in a right direction and make sure I am not misinterpreting things.

After I find a sample in the street (nail, hair, cigarette, chewing gum) I go to the bio lab and extract the DNA out of it. Then I end up sending things out for sequencing and get these data back in the email. Afterwards, I feed the data into the computer program to generate the 3D model. On getting the model of a mask, I add finishing touches. For instance, I paint the eye color on the 3D model by hand. Finally, that model is sent to the 3D printed and is printed in full color.

I go through the step of looking at specific traits of the DNA. It is a pretty slow process for me now because I don’t have a big budget. And it is still in progress; being something I am still researching and experimenting with. I am now trying to build up a panel of traits that I can look at for each sample.

- Your “Stranger Visions” project looks very similar to the art practices of Sophie Calle. The French conceptual artist also works on the intimate territory of unknown personages. In particular, her ‘Hotel’ series (1981) come to my mind where Sophie Calle had been working as a housemaid in the hotel delving into the personal things of guests while cleaning their rooms. She also did this dazzling project ‘The Address Book’ (1983) when she was calling all the individuals from the contact list of a found notebook in order to investigate as much information as possible about its anonymous owner. I was wondering, if you ever had this feeling of obsession or mania to get closer to the holders of your DNA samples? Or is this project just constrained to be the collection of ephemeral portraits?

- It’s a really good question. I think the connection with Sophie Calle is great. Her work is really fantastic. I do have a very intimate relationship with these, essentially, pieces of data. It has crossed my mind to do things like these in a more stick out fashion. For example, I could wait around on the street with the covert camera for someone who would have dropped a cigarette and then snap it and follow them. But in my view, the reason I deal with as much as I have gotten in this project in the science world is because it is anonymous. And if I would start tracing these things back to the actual people – then it becomes ethically really ambiguous. Potentially I know about them things that they don’t know about themselves. I have the ability to look at these traits for various risks of cancer or heart disease. A lot of people whom I talked to – friends of mine, don’t want to know that part of information. Therefore, if I would have the relationship with this person our liaison would have much different dynamics. So it is a really interesting area to explore. I think, probably, in purview of this project I will remain working mostly with strangers.

- This is also the reason you come across a dilemma of making the software open source and available to other people. It is almost similar to the currently discussed problem of publishing instructions for printing guns online, which means that Internet users could easily download it and make weapons on 3D printers without any control…

- Exactly. This has been one of my dilemmas with this project. First of all, whether to open source the software? Period. What could someone do with that software? Secondly, now when the project is publicized and people are contacting me, I have started getting actual contacts from people in law enforcement area and things of that nature. For me this is an interesting situation that has two options. You could stand outside of this system and critic it. Or you may engage inside the system with someone who is critically aware. These are all things that are happening right now and which I am trying to think through myself.

- Trying to define the level of your own responsibility?..

- Definitely. Because one possibility is about standing on a sideline and saying “this is a problem”. And another thing is to actually engage with the acts that could become problematic, I guess.

- But now you have started sharing the software with people. Am I right?

- Yes, there are one or two people that I have shared with. The main criterion for me is that I know these people personally being able to realize what their intentions are. That has been my approach since the first time I started working with the software. So I am sticking with that for a moment.

- How would you define yourself in terms of working in the system of new media arts?

- I guess, for quite a while I have thought of myself as an information artist. There is one thread that turns around my work, which deals with different concepts of information. I am questioning how we process the information and how we are dealing with information on different kinds of conceptual levels. I think this is probably the most accurate term.

Public art installation in Utica, NY Jan. 25 - Feb 25, 2008

- In addition to more conceptual projects you are also working with robotics and sound pieces. Have you been thinking about combining Stranger Vision project with other areas of your work (perhaps, robotics related projects)? The reason I am asking this is because the portraits you create certainly represent a vision of the machine. These masks produced by 3D printers using specific software and codes in some sense an attempt to project the gaze of the other on us as human beings… Have you ever had an idea of expanding your experiments with the DNA to a broader scale?

- Conceptually I totally agree with you that this project is about how machines could see us. It is really about the things that are empirically observable. I haven’t really given much thought how I would combine this project with other media. Mainly because I think I am so much in a middle of it. And feel like there is so much work up to do. I have been working with this project for a year now. And every 6 months I take a break and exhibit what I have so far. So I do these periodic ‘work in progress’ exhibitions. And maybe the project will always be just a series of works in progress that gain accuracy over time.

- The history of artists working with DNA is relatively quite long. There is an iconic creation by Eduardo Kac called “Edunia” (2003-08) which is a genetically engineered flower – the hybrid of Kac and petunia. This plant is partially flower and partially human since it carries the actual artist’s genes. In 2004, Shiho Fukuhara and Georg Tremmel planned the “Biopresence” project and decided to transplant the human DNA into the tree explaining it as ‘a living memorial for a person’.

- It is like carving your name on a tree.

LK: Аbsolutely. How would you characterize the DNA as an innovative material in art? And what is the relation of works that are based around DNA issues to a broader theme of body in art?

H D-H: First of all, I think of the DNA is an information system. Being an artist who works with algorithms, making software etc, I understand that DNA is just like another kind of code. And this feature makes it so fascinating, because you have this incredibly complex and incredibly simple code. And on the flip side of that is a fact of DNA being an incredibly personal, intimate body of information (yes – it’s a BODY of information) so tight up in our identity. What is fascinating to me is that this is a visible component over identity.

What do you do when something invisible suddenly starts becoming visible? How are we going to deal with learning about the DNA? These are really the questions of the moment, I think. People are increasingly sending samples to get analyzed to such public services like 23andMe that are letting people to look at some of their genetic data. So we are progressively going to have figure out how to handle living in a world where something invisible is becoming visible.

For that reason this is a good area for artists because art is so good in dealing with such critical, conceptual, personal questions. It helps to define which processes happening in the area are ethical, and which are aesthetical, including all the questions around the main problem. We are in the time of great transition, and time changes things so quickly. Therefore, I think artists are really good at addressing those moments of changeover.

- You are not only working with hair as the source of DNA (you use nails, cigarettes, chewing gums). But it started with a hair. Does hair carry any symbolism for you? Obviously, hair as the most visibly living organ is a brilliant manifestation of living (and, someone said, it is the body’s living graveyard since hair consists of dead cells). The loss of hair if often associated with the loss of identity if we start thinking about rituals of shaving while entering into the army, associations related to loosing femininity while cutting your hair, loosing health, loosing acceptance within the community through the humiliating ritual of having your hair cut in the earlier times…

- Yes, hair has this very ritual history. It is very tight up in our sense of ourselves. Loosing once hair is a very intense emotional experience. For me it is also just a personal thing because, for example, I am always running my hands through my hair and dropping tons of it that goes all over the place…

- You have worked with many spaces supporting art & technology initiatives in New York like Eyebeam, and Genspace. What are the other places you had a good collaboration with as an information artist?

- Eyebeam is a real touched for me and for a lot of tech scene in New York. I did a residency in Clocktower. They have a tradition of supporting avant-garde media and sound projects. But at the same time they have different new media artworks. I partnered with a lot of non-traditional spaces, emerging gallery spaces in New York. I was recently speaking with someone from New York Public Library and I feel like that would be really amazing place to exhibit the Stranger Vision project. This work is so related to history and the ideas of knowledge and science. I am thinking about the significance of having it in a library, which would be great.

- Do you have a suggestion about the ideal residency for you?

- For me it would be doing residency in a real hi-tech lab.

- … so the equipment is the most important aspect, isn’t it?

- At the moment, the bio lab aspect of my current project is the slowest part of this process for me. That's why, if I did a residency in some place where they do this kind of work regularly I could just go through it so much more quickly. I could iterate the technique at a much higher phase, which would be fantastic.

Prerious interviews INCERTAE SEDIS with Brittany Ransom

Lilia Kudelia