Live on screen

PERFORMANCE art is a tricky proposition for museums. Marina Abramovic apart, individual artists do not usually perform their works for days on end. Nor are most art museums geared up to present extensive programmes of live events. Yet artists are increasingly working with live action and bodies, so figuring out how to present it all has become a priority.

London’s Tate Modern, the world’s most visited modern-art museum, is managing this problem in two ways. The museum is creating more space for these live works, with a new building and access to massive underground tanks (once part of the former power station that houses the museum). Tate is also harnessing the limitless space of the internet. Tate Live, funded by BMW, a German carmaker, is a four-year experiment in live performance on YouTube.

The form is hardly new—think Kurt Schwitters, Bruce Nauman and innumerable "happenings" of the Dada movement onward. But these live-action works have had “an invisible history in the museum,” says Catherine Wood, Tate’s curator for contemporary art and performance. The YouTube channel aims to change this. The eight works already posted online (out of 20 planned for the series) suggest that the approach is not only bringing this work to a broader audience, but also is creating a new artistic form.

The format is straightforward. Performances are shot by a single camera without audience in a white room, and range in length from ten to 40 minutes. They are streamed live to viewers around the world, who comment on the art and a follow-up discussion via social media. The event is immediately archived and posted to the museum’s YouTube channel, without any post-production editing. The works thus inhabit a strange new zone: they are neither fleeting experiences for a live audience nor refined works of video art.

“It’s the best and the worst of both worlds,” jokes Nicoline van Harskamp, a Dutch artist whose “English Forecast” was performed live last week. “A live thing that will stay online forever!” Usually a performance work is gone instantly, and is either not documented (as in the work of Tino Seghal, a Turner prize nominee), or edited before final presentation. Still, viewers may be forgiving of glitches, Ms Van Harskamp hopes. “It’s a completely new thing.”

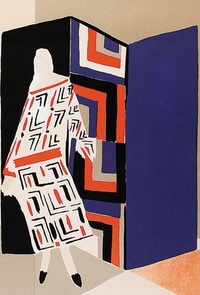

The form’s potential so far outweighs the negatives. Participating artists, including Joan Jonas, Lui Ding and Pablo Bronstein, have found performing for an imagined global audience intriguing, says Ms Wood. “English Forecast” in particular seems an ideal synthesis of subject matter and medium. The spoken-word compilation performed by four actors (pictured) is a tapestry of voices speaking in the world’s newest—and least noticed—language: non-native English. Several billion people now speak English, and non-native speakers outweigh native speakers four to one: the topic is a compelling one worldwide.

“We are not going to speak like you, ever,” a Portugese speaker intones. “English, it helps us to come together, but it does not unite (u-neet) us,” says an Italian. “Like a modern way of colonisation,” says another, each actor switching between accents and syntax from 34 languages. Ms Van Harskamp sampled comments from hundreds of Tate’s 5.5m annual visitors and staff, inviting YouTube viewers to repeat the words via subtitles in the International Phonetic Alphabet. Understanding what the voices are saying is harder for native speakers than non-native: this is part of the point. The new question is whether English will consume other tongues or generate a multiplicity of dialects.

Performing on an empty yet virtually teeming global stage is bound to alter how artists conceive their work, Ms Wood observes. In Ms Van Harskamp’s case, the experiment allowed her to reach the global audience her piece addresses. About a thousand watched it unfold live; viewer numbers for archived works are a few times that. But it is early days. As one non-native speaker said, in a strong Hebrew accent, live online performance is still “one feet in, one feet out.”

www.economist.com