Gijsbert Hanekroot: 'The magic of photography still intrigues me'

We asked the well-known Dutch photographer, guest of the Kyiv Photo Week 2017, to talk about his famous series of portraits depicting iconic rock performers of the 70s, visual culture and how photography has changed in the 21st century.

How did you get to know about Kyiv Photo Week and what inspired you to come?

Me and Tetiana Tuchyk (art-manager, incl. G. Hanecroot’s manager – ed.) have been friends for seven years. In 2013 we arranged a big exhibition in Moscow together, in The Lumiere brothers Center for Photography. And it was Tetiana, who contacted me about this show. I’ve been here, in Kyiv, once before so this is both a good reason to show my work and also to be in Kyiv, which I like.

Abba. Anni-Frid Lyngstad, 1976. By Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

What did you bring for us to see at Kyiv Photo Week?

My kind of portfolio, called Abba-Zappa (Abba... Zappa Seventies Rock Photography – ed.). It is a photobook / portfolio about rock scene of the 70s and it’s from A to Z. In the 70s I kind of covered the whole scene, I call it the Golden Age of rock music. My exhibition at Kyiv Photo Week presents about 30 photos, covering this side of my work. Just rock music.

Have this exhibition been to different countries?

Yes, it came from Antwerp in Belgium, straight away, where it had been for a couple of month.

And it’s being really popular!

Yes, it’s going to Los Angeles in February.

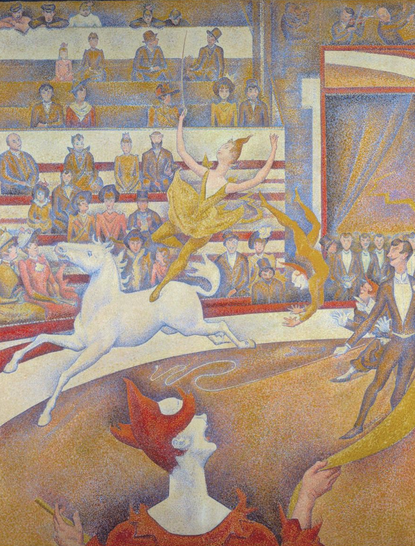

Mick Jagger, 1977. By Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

I’ve heard that you stopped shooting in the 80s.

Yes. During the 70s, from 1969 till 1983, I was a freelance photographer, but then I stopped and changed to different type of work. When I was making this book in 2008, I went through my old photos and realized that they were better than I had remembered. I actually have started to shoot digital from the beginning of the 21 century and couple of years later I’ve become a photographer again. But the difference is that I don’t have assignments anymore, I work for myself.

How would you define photography?

I think that the interesting thing about photography is that first of all you have to see, use your eyes. But I realized that a lot of people, they don’t see, they don’t have a feeling for art or just don’t see it. That is one part, but then the other is to make a good photo. You have to see it but you also need to be able to catch it. I mean, you can only try, and if you have some experience and talent, you might succeed. Sometimes I think “Okay, this is a good photo”, but it’s difficult to catch that process and that’s what I like of it. This kind of magic, in a way, and that is very special for me. It still intrigues me.

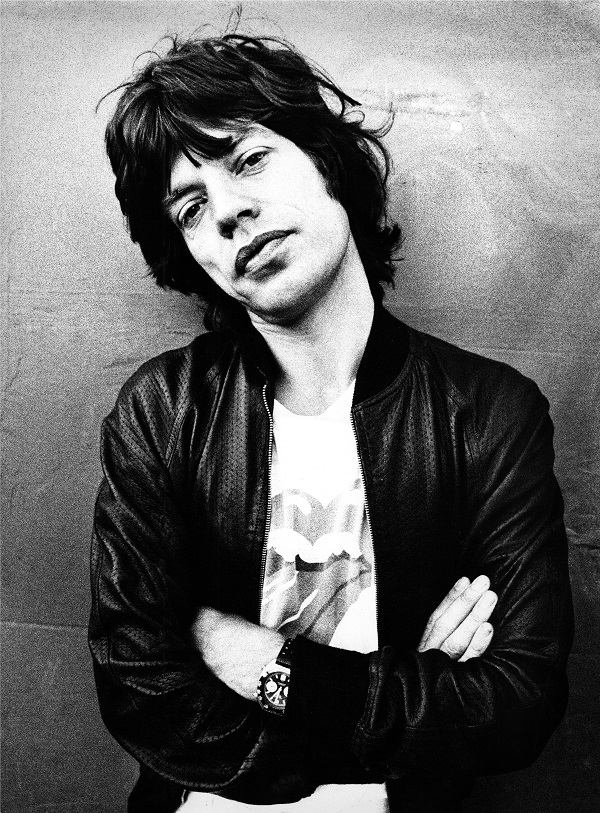

John Lennon and Yoko Ono, 1971. By Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

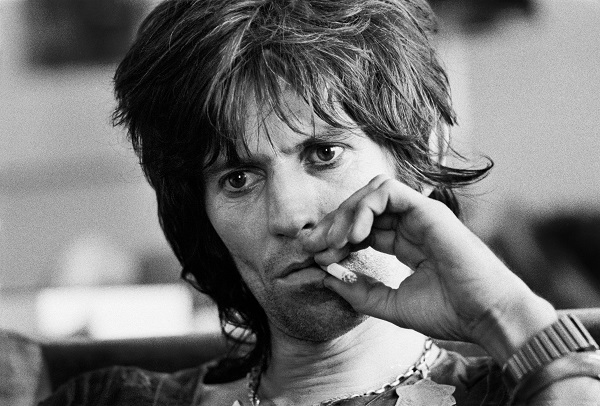

Keith Richards, 1976. By Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

How do you choose the topics for your photo series? For instance, why did you decide to shoot the rock scene in 60s-70s?

It was more or less by occasion, it just happened. I had a friend who was working for an underground magazine and he was doing interviews with rock stars. It could have been something different. At first I was there not so much for the music but for taking good photos. Then after a while I started to listen to music a lot because, you know, I covered 2-3 concerts a week and more. Over time I started to have my preferences, some groups I liked, and that is how I became a rock photographer.

You were a photographer in 60s-70s, but then changed your occupation and have returned to photography only in 2000s after an about 30-year break. What is the difference between being a photographer in the 20th and 21st century? Not only talking about digital and analog cameras.

In a way it hasn't changed. I mean this process is still the same. Of course, the technique is different, which is helpful, everybody nowadays has two or three cameras unlike it was in the past, but the circumstances for photographers are much more difficult. You know, magazines and newspapers, they more or less don’t pay any more. That is all the technical and practical side, the more important thing is the quality, making a good photo. A lot of people are photographing, you see a lot of good photos, but you also see a lot of not good photos. More (smiles).

What is the most important thing for you to show in portraits?

This kind of a secret thing, the magic I was talking about. Portraiture is one of my strongest sides as a photographer, and yet from all the rock stars I've photographed I have about 15 portraits that I consider good… very good (laughs). And then, when I show them to somebody, they might say something like “Oh, nice old man”, you know? They don’t see it, what I’m talking about or what I’m meaning, and that is kind of interesting. I don’t understand why they don’t see it, but that’s the way it is (laughs).

David Bowie, 1976. By Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

Do you have any secrets of successful music photo shoot?

The secrets? No. The circumstances are important. The secret is that you need to have the ambition to make a good photo. And that’s one of the reasons I have stopped, because I came home with photos of, for instance, Bowie that were not as good as those that I already had so clearly my motivation was disappearing. As I explained, the process is difficult to catch, you have to concentrate and be motivated to make a good photo.

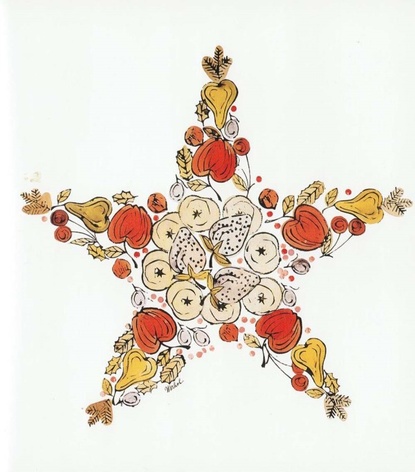

Talking about your another project, a book called De Sovjet-Unie bestaat niet meer (The Soviet Union no longer exists), what caught your interest about this soviet topic and how did you come up with the idea?

Me and my friend Theo Bakker were on a trip for 4 weeks, visiting Potsdam/ Berlin, Brest, Minsk, Saint-Petersburg, where I had an exhibition, and then Moscow, Kyiv and back. Theo was writing. And at the beginning of our trip I didn’t have the purpose to make a book, but I started taking photos and he started writing. After one week I realized: we should see what is going to happen out of it. And when we came back we decided this is good enough to do a book.

The cover of a book De sovjet-unie bestaat niet meer

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

What was this particular thing you saw during your journey that you wanted to show?

That’s a difficult question for me, because the main purpose is to make a good photo. In a way, it is an isolated thing: all you need to know is if the photo’s good. But when you make a book it’s more complicated, there should be a story in it. The written text is the story, people we met, circumstances we described, and the book is divided into chapters, dedicated to different cities/countries. But I also hope that, not on purpose but as a result, if you go through the book and you see the photos, then it will give you a good feeling, because you like the photos and the text. That would be enough.

From the book De sovjet-unie bestaat niet meer

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

During your stay in Kyiv you could probably notice that the visual culture here is not that well developed. I am talking about the things that you might have seen on the streets, in public space. What do you think can be done to make it better?

It is not so bad. I was walking around and I agree that there is a kind of backlog, but it has to do with money as well. I think there are enough people that are interested in art and are working in art so it might help, if the government subsidizes or having projects subsidizing artists and facilitates the development of this field. It is not working like that now, probably. But it is the same in Holland: this discussion is now going on there as well, because the government does not understand that art is important. Last week I read what someone had written in a newspaper: “Democracy might be important, but art is as important as democracy”. It is a basic human need. You have to develop it and the government should realize it’s importance. So go on! (laughs)

From your experience as a photographer who is already well-recognized out of your country, what qualities should one have, both as an artist and a personality, to achieve world recognition?

I’m not sure I know the answer to this question. It is complicated, because, talking about myself, as I explained, I stopped being a photographer, so I still don’t really know if I am an artist. I mean I know what I like, what is beautiful or what gives some emotion, touches me – that’s actually the main thing. Now I might say that maybe I’m an artist, but not in a way that art is all I have to do, because for 30 years I did something different. I still did watch photos, but I didn’t take photos. But I know there are a lot of people that just create things, just because they have to do it. And that will ever exist, so don’t worry, people will make beautiful things at the end (laughs) and beautiful things will achieve recognition for sure.

In the age when you started taking photographs, you were supposed to have certain skills to be considered a good photographer. Nowadays one can become a real artist just making some photos on their smartphone. What is your attitude to this change?

If you have a lot of young children playing football, you have better football players. Nowadays they start at a very young age, millions of young boys and girls, so you have better quality. The same thing with smartphones: if everybody is taking photos you might have better photographers at the end, I don’t know. Actually, it doesn’t help, people, about 80% I think, still don’t have the capacity to view and that’s where it starts. You have to learn to view, to use your eyes.

The other thing is that you get bored of it. The visual perception is overloaded, I mean, you notice like 1 billion different features a day or so on Facebook.

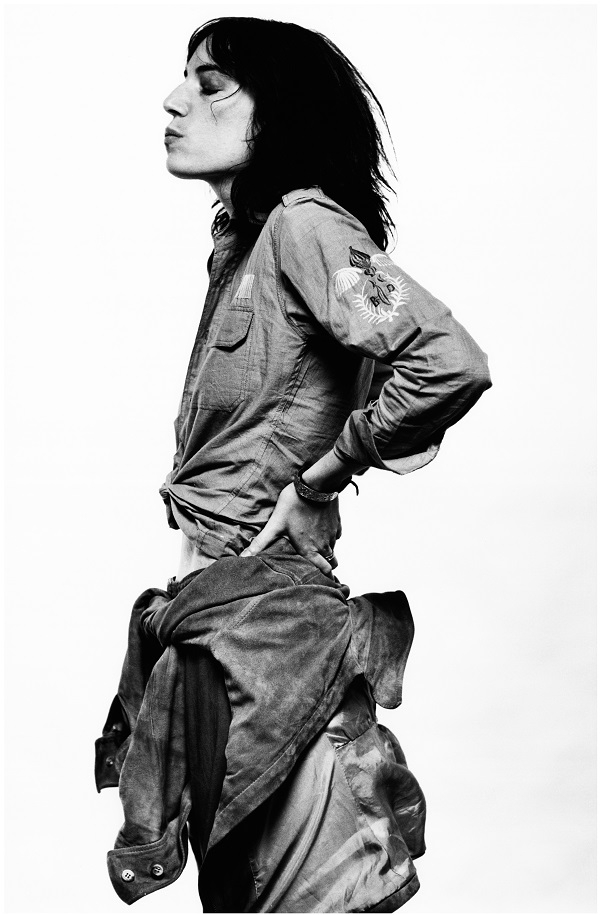

Patti Smith, 1976. By Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

Do you think that we cannot escape this process, we just need to learn to live with it?

No. No, no, no. We will escape it in the way that people between 40 and 60, they are on Facebook, but the younger people, they are not on Facebook and are changing a platform every year. They get very easily bored. So they will get bored anyway and will start to use pencils (laughs).

Well, they’ve already started to use analog cameras.

That’s more a kind of hype thing. You pay more attention, the process is more complicated so it might also force you to use your eyes better. You only have 12 or 36 photos to shoot, mind you.

Talking about young people, what is your advice to the young generation of photographers?

Taking a lot of photos.

Practice?

Practice, yes, but maybe not too much with the smartphone. But if you can watch, then you can use the smartphone, it doesn’t really matter. The technique is not the important thing.

Gijsbert Hanekroot

Courtesy of Gijsbert Hanekroot

About Gijsbert Hanekroot

Dutch photographer Gijsbert Hanekroot (Brussels, 1945) started his career as a photographer of rock musicians in the late sixties. Back then, the rock scene was not quite the well-oiled machine it is today. Things still had to be invented: light installations, sound, promotion, organization, crowd control. This also applied to music journalism and photography. Almost every week, new groups were being discovered. Every single day, people were learning things and adapting them.

Hanekroot’s development as a photographer essentially ran parallel to developments in the music scene. He travelled frequently and came face to face with the music icons of that period. His photos can be divided into four categories: concert photos, studio photos, portraits and photos made at press conferences.

Gijsbert stopped being a professional photographer in 1983 and changed his occupation, but has returned to photography in 2000s. A few years ago he also began to digitize his archives. This led to the publication of Abba..Zappa Seventies Rock Photography and exhibitions in a.o. Paris, London, Moscow, Tokyo, Frankfurt and Amsterdam.