Nadim Samman: «Art is the game of generations»

As far as it is understood from your curatorial practice, you position yourself as an independent curator. What are the characteristic aspects of your practice? What are the ways in which an independent curator today is integrated into the existing system of the art market, how does he find his niche?

The term ‘independent curator’ seems straightforward, applying to those who are unaffiliated with any particular organization on a permanent basis. But independence – which has a rhetorical whiff of emancipation – is more opaque than commonly supposed. This ‘role’ is inconsistently defined across institutions, if at all. This situation partly accounts for the recent emergence of 'curatorial studies' literature. As a publishing genre and emerging academic field, it tends to announce that curating involves a set of proprietary skills and concerns. I am skeptical that, intellectually, Art History departments cannot handle the conceptual parameters of what curating is. However, asserting the existence of independent curating is an important message to convey to the mechanisms of employment in the artworld. A brief trawl through the few useful open-call platforms should be enough to convince anyone that advertised opportunities are like needles in a haystack, and those announced are rarely paid. If they are, it is poorly. Moreover, the independent must defeat a multitude of other candidates. Temporary engagements are also predominantly run as competitions, requiring significant investments of energy. Beyond being asked to submit a curriculum vitae and letter, the independent must commonly deliver a detailed project concept – and often budget – on spec. This means doing most intellectual and research work in advance of winning, then giving one’s idea away without retaining any rights in case of rejection. Unlike architectural competitions, no shortlists are published or publicized. Again, the independent suffers a lack of visibility. In other words, the apparent market for their services is irregular, unregulated and fragmented. It would seem, then, that the present structures of the artworld furnish too little opportunities for independent curators to exist. But we do…

Nadim Samman

Those with a predilection for ontology will recall Heidegger’s observation that ‘being-alone is merely a deficient mode of being-with’. Let's replace the first conjunction with ‘being-independent’. The independent curator is not separate from but rather with multifarious institutions and patrons. This does not preclude the fact that he is, more often than not, unseen. So many independents are sweatily with the artworld, working day and night, but invisible to the objects of their attention. To be economically viable, the independent must be capable of effecting being-with such partners in their respective fields of vision. The independent must cut the clearest silhouette possible in each scenario, sometimes wholly different than the one preceeding. He must be the curator of his own images in order to be rendered the resources to handle ones that do not belong to him. This is not a question of intellectual backbone. Curate what you will, if you can. I am addressing the conditions of this if.

An open-call or job advertisement is an image of what an independent curator looks like – economically, professionally, and so on. It is far more interesting to be the author of your own professional image and create your own context for partnership. Long before an exhibition opens, the agreement between the independent curator and the commissioning patron represents the consummation of a professional seduction. Seduction is the right term when, in so many cases, the commissioner does not broadcast a desire for servicing, nor comprehends one before meeting the independent. Whore or – better – Lover, the independent must the make first move.

Once you get into bed, there are the mechanics of curatorial coitus itself: A good curator plays the role of a double agent, representing both material exigencies - including the patron or commissioning institution's needs - and the artists will. In addition to this, he smuggles in his own artistic interests. He is both an accomplice and an agent provocateur. Curators don't always write, but they should. Having said this, the best justification for making an exhibition is that what is being communicated could not be put across better in another format. The only niche that matters is excellence.

You combine the roles of curator, journalist and teacher. In all of these areas do you apply a study within a single perspective, or you essentially allocate the spheres of your interests?

What cuts accross all these roles, for me, is a desire to judge, teach or work with art from the position of enthusiasm. Art is a game we play accross generations, and in partnership with people we might never meet in person. Perhaps one aspect of this game is a constant reimagination of its own rules, another the reimagination of its consequences. All engagements with art are primary contributions, even commentary and pedagogy. As a great violinist once said, ‘I never practice, I always play’.

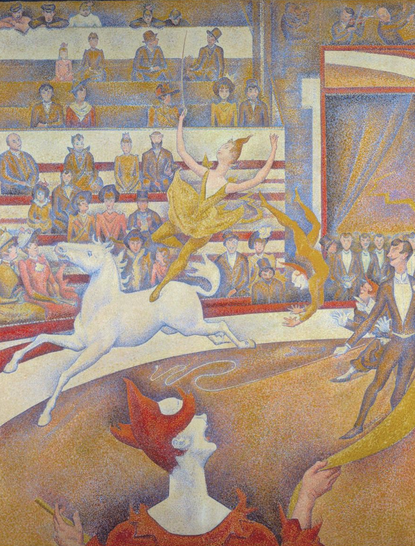

Treasure of Lima: A Buried Exhibition (2014). Photos: Julien Charriere. Copyright TBA21

You work with the theme of the peripheral geography, in particular, with the theme of "the end of the west". Do you or have you paid attention to Ukrainian context within this research?

My PhD focused on the international reception of late-Soviet art in the US in the 1980s and 1990s, particulary in the museum and critical context. Its function was to examine the construction of ‘international’ artistic discourse in the late 20th Century. This study, which concentrated on Moscow Conceptualist emigres such as Kabakov and others, sharpened my appreciation of the fact that centres and periperies are not defined by absolute metrics. Politics – or ideology – and economics always play a role. Questions specifically related to the Ukraine did not apply, however, I hope I have absorbed a general understanding of Ukraine’s late and post-Soviet cultural conditions. Beyond this academic background, I had a chance to visit Kiev two years ago to conduct artist studio visits and make connections with colleagues in the museum field.

The idea of peripheral geography is something that I have been developing in recent curatorial projects. While the concept could apply to the question of national art scenes that are less ‘integrated’ with hegemonic (Western) art power, this has not been my agenda. I have, in fact, been engaged with testing the function and relevance of art in extreme geographical peripheries. My project Treasure of Lima: A Buried Exhibition took place on an uninhabited pacific island. It was an exhibition that nobody saw. My Antarctic Pavilion (Venice Biennale of Architecture and Art) is premised on the idea of an artistic embassy for a continent where sovereign (national) claims are suspended.

Treasure of Lima: A Buried Exhibition (2014). Photos: Julien Charriere. Copyright TBA21

Working on your projects, you frequently work with artists who are representatives of different regions. Your project Antarctopia on the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture was designed to question the mode of presenting the projects at the biennale on a national basis. Is such "watershed" relevant today (identifying the artist as a representative of a certain country)? Are the artists from Ukraine perceived in such way?

As everyone in Ukraine is aware, the issue of national identity is as charged today as it has ever been. This is the case in many parts of the world. At the same time, however, the global economy, air travel, mobile communications and the internet are facilitating new modes of identification and organization. New poltical formations are developing in line with this – think of the Pirate Party, which operates accross borders and is active in Sweden, Germany and elsewhere. Its basic agenda is free data. In fact, think also of ISIS. Through this group retains much archaic rhetoric, their – horrible – operation is highly reliant on new communication technologies. It is important that our cultural institutions are not totally out of touch with these conditions, and that they can absorb some lessons in order to better represent or nurture positive developments. Predating today’s context, the Antarctic Treaty represents the most successful transnational cooperative scheme ever established. The Antarctic Pavilion is committed to the idea that the treaty paves the way for a truly post-national (and peaceful) construction of citizenship. Imagining the relationship between local structures, which include brick and mortar, and new network formations is an important task for cultural work. This applies no more to Ukrainian artists than it does to others.

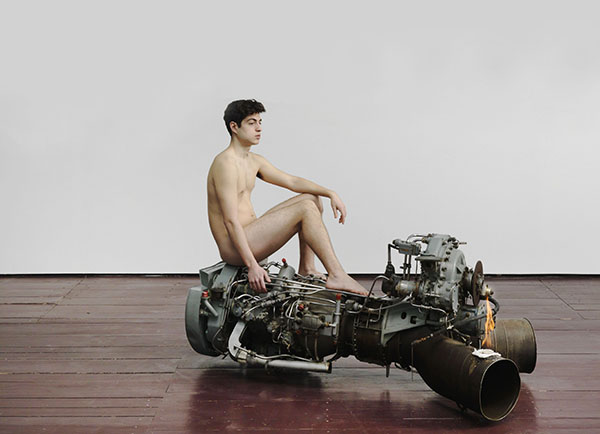

From the project "Rare Earth". Roger Hiorns. Untitled (2012). Photo: Jens Ziehe. Copyright TBA21

Do you follow the development of the Ukrainian art scene? What projects of recent years can you outline? Have you visited (maybe something attracted your attention) any projects outside Ukraine with the participation of Ukrainian artists?

When I last visited Kiev I arrived with a very limited perspective on recent artistic developments. After meeting with artists from the R.E.P Group, Alevtina Kakhidze, Zhanna Kadyrova and others I began to gather some.

In your projects you work with both young and experienced artists. Who is easier to work with? And do you feel the difference working with them?

Older artists can sometimes have more fixed ideas about what they want out of an exhibition in terms of scenography etc. Younger artists who have had less opportunity to present works in larger spaces are often more open-minded about this topic when invited to bigger projects. Developing a strategy together is more interesting for me. On the whole, however, it is hard to generalize about differences. Great artists, no matter what age, always surprise you.

Why is it important for you to participate as an expert in the contest for young Ukrainian artists MUHi 2015? What made you take this role?

During my first contact to the Ukrainian artistic scene I was impressed by the intellectual generosity of the artists that I met. I feel honoured by the invitation to play small role in this context. Artists from all countries have valuable contributions to make to international culture. But exchange is always a two-way process.

From the project "Rare Earth". Suzanne Treiser. Rare Earth (2015). Photo: Jens Ziehe. Copyright TBA21

Editor of issue: Olga Kucheruk