Folkways and Fantasies: Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern at The Ukrainian Institute of America

Andrew Horodysky

An exhibition of 29 paintings by scholar and artist Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, entitled Folkways and Fantasies, opened on Saturday, February 27, and remained on view through March 9, 2016. Employing deceptively simple Jewish folk, religious, and cultural historical scenes as his foundation, Petrovsky-Shtern’s works chronicle and illustrate complex embodiments of real human celebration, drama, tragedy, and survival. The exhibition was Petrovsky-Shtern’s first appearance with The Ukrainian Institute of America. Introduced by Walter Hoydysh, PhD –– director of Art at the Institute and exhibition organizer –– during the opening reception, the artist graced an audience of about 200 attendees with a vigorous and compelling introduction to his artworks.

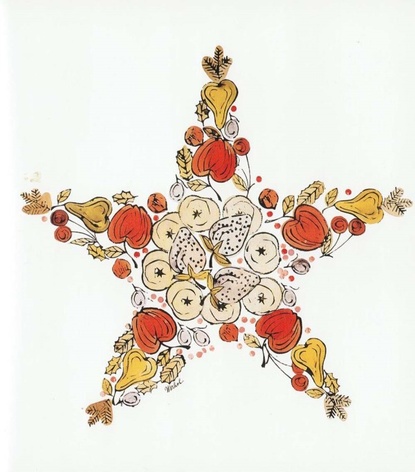

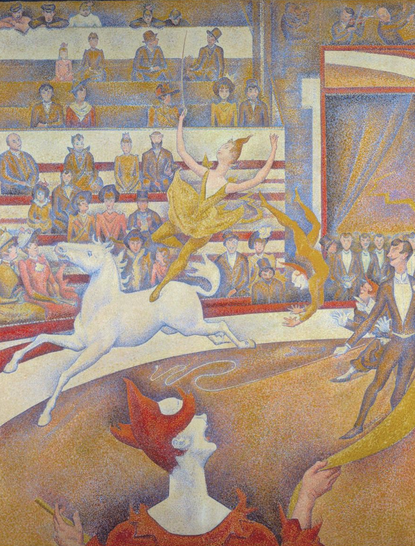

The visual, social, historical and cultural –– Jewish and Ukrainian –– cues in Petrovsky-Shtern’s serial paintings set a stage in preparation for a demanding journey through an existential dreamland. Set within four distinct groupings: Fairy Tales, Icons, Circus, and Nightmares, the paintings, adroitly displayed throughout the elegant and well-appointed backdrop of The Ukrainian Institute’s second floor, manifested a deep personal narrative, colorful and troubling, yet, fundamentally humanistic on every level.

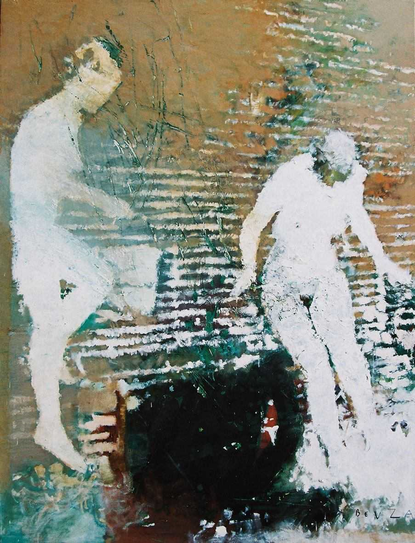

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Carpathian Dream, 2009, acrylic on canvas, 61 x 61 cm. Image courtesy of Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern

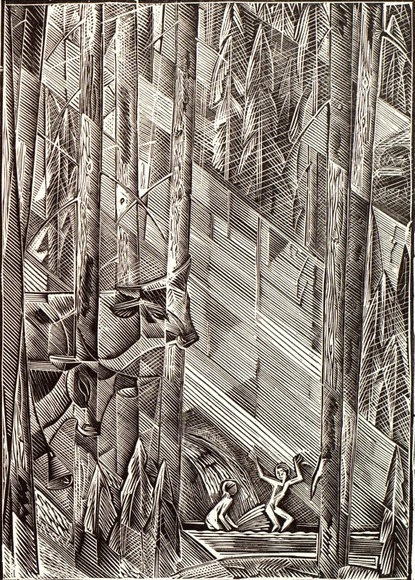

Born in Kyiv, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern grew up in a cultured and assimilated Jewish family. His father, Myron Petrovsky, was a noted literary intellectual and scholar in Kyiv whose intimate circle of friends included accomplished artists and writers such as Andrii Biletsky, Leonid Pliushch, Yurii Shcherbak, Vadym Skurativsky, among others. Petrovsky-Shtern remembers studying with such painters as Boris Lekar, Mikhail Turovsky, and most importantly, the realist painter and satirist David Miretsky, who agreed to take the young Yohanan on as a private student. Miretsky encouraged him to develop his talent for drawing and engraving, which he said suited the boy’s dynamic, graphic style.

But, Miretsky’s training was cut short. In 1972, terrorists murdered 11 members of the Israeli Olympic team in Munich. Miretsky went with a small group of Jewish mourners to commemorate the tragedy by placing flowers at Babi Yar. “They went there because there was nowhere else to go,” Petrovsky-Shtern explains. “They were arrested for ‘hooliganism,’ just to scare them with a warning. After that event, the person to whom I was a disciple lost his job, packed up and left. The only person I wanted to study with was no longer there.”

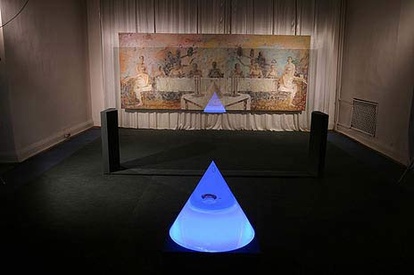

While Miretsky left for New York, Petrovsky-Shtern lost not only his personal instructor, but, also his model of how to be a successful Jewish artist in the then Soviet Ukraine. By 1979, as most of his father’s artist friends had emigrated for the United States, Petrovsky-Shtern decided to pursue an academic career, first studying Judaism, then turning to Latin American studies. He studied Spanish and earned a doctorate in comparative literature from the University of Moscow, and eventually became a professor at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv. In the meantime, he studied the works of Andrei Rublev, an icon painter, and Maria Prymachenko, a Ukrainian folk artist famous for her brightly colored painting of animals, nature and village life. He drew from their works to create a large fresco that depicted Jesus Christ as a kozak with a saber and Mary as a villager carrying a bucket, enveloped by a pantheon of former artist acquaintances and teachers.

In the exhibition’s fairy tale paintings, for example, bold, fantastic images –– a folk motif-embellished wolf in a Ukrainian village landscape, a green elephant surrounded by villagers, disproportionately oversized insects –– all appear straight from past village lore and the artist’s conflicted unconscious. In Carpathian Dream (2009), an over-sized multi-hued bovine figure occupies the center of the globular composition, posing as the bedrock of the village family’s immediate universe, a celestial host foundation. A source of subsistent nutrition, warmth, and even joyous companionship, the restive cow is oblivious to the activities of its inhabitants. Is the family at leisure –– mother coaxing her young son for a playful walk along the path encircling their thatch-roofed house, father dreaming after a long day’s work? Or, is mother desperately dragging son away from home, escaping the village from certain menace, as father fixes his ear to the ground, anxiously listening for approaching danger? These are the capricious observations Petrovsky-Shtern demands of his witness. Colorful scenes of stasis and certain fancy quickly double for the ever-awareness of the fragile.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Exodus, 2012, acrylic on canvas, 91.4 x 91.4 cm. Image courtesy of Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern

When asked where the historian’s academic discipline ends and the artist’s practice begins, Petrovsky-Shtern responded to his self-imposed question, “I put on canvas what I cannot and do not want to say out loud in a classroom or put on paper. Some of my paintings convey the mythological idea of ‘always’; this is what always happens to the Jewish people. There are paradigms in history that repeat themselves, such as the events of 70 CE, 1492, 1648, or 1942, that all show the highest level of anti-Jewish persecution and destruction of Jewish life. On the contrary, in my research I am working against this idea, debunking myths and showing how different are the events that the national memory claims similar.”

It is important to consider that at first glance, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern’s paintings appear, to the uninitiated, innocent within a severely reduced formal and conceptual range that connects them more to outsider or naïve art, if not familiar shtetl representations of the past by the likes of Marc Chagall, for example. In further series –– Circus and Nightmares –– of paintings, his still diminished palette is chosen deliberately and often with an acknowledged reference to Soviet avant-garde art of the post-revolutionary era, using only red, black, and white; what emerges is a cut-out aesthetic, lacking coordinated dimension. (The artist half-jokingly declares that he doesn’t know how to use color!) Also, is his emphasis on pure geometrics, a reductive device that recalls El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin, among other politicized artists. These aesthetic conventions vehemently critique the leading realist traditions that came to the fore in the Soviet state under Stalin, aligning Petrovsky-Shtern’s output with the artist-critics of that state.

By keeping his color, form and narrative devices to a minimum, Petrovsky-Shtern delivers an impactful graphical experience, affording the viewer a direct admittance to his pictorial and symbolic representations. To illustrate, Exodus (2012), a medium-sized canvas, portrays a Jewish family is portrayed seated in a paper boat –– not unlike the kind children construct for their enjoyment –– on which is elegantly penned Hebrew text telling the story of Exodus. The boat, with the silhouetted figures, floats on a red violent sea, drafted as rhythmic talons gripping its captive occupants, all against an uncertain black background. Despite the sensitive affection the figures display toward each other, disaster is imminent.

The dynamics of –– and observed conflict between –– Petrovsky-Shtern’s ethnic identity and political critique are centered in both the simplicity and complexity of his creative choices. His paintings personify fragile survivors who represent the struggle and strength of the Jewish experience throughout Eastern Europe, specifically Ukraine, and, more widely, the vulnerability of humanity. Folkways and Fantasies exhibits and challenges many of the sheer visceral themes related to human nature and existence, the challenges and decisions faced by unique individuals and as a society, and, the way choices are forced upon them for response and action, or inaction, the tensions between hope and despair.

From left: Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Olena Sidlovych (executive director of The Ukrainian Institute of America), and Walter Hoydysh (director of Art at the Institute). Photo by Pavlo Terekhov

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern currently serves as the Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies at Northwestern University in Chicago. He is the recipient of the 2008 Northwestern University Distinguished Teaching Award, the 2011 American Association of Ukrainian Studies Book Award, and the 2014 National Jewish Book Award in History. In addition to numerous published articles and essays, Petrovsky-Shtern authored such scholarly books as Jews in the Russian Army, 1827-1917: Drafted into Modernity (2009), The Anti-Imperial Choice: The Making of the Ukrainian Jew (2009), and The Golden Age Shtetl: A New History of Jewish Life in East Europe (2014). Past exhibitions of Yohanan Petrovksy-Shtern’s paintings were held at The Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art (Chicago), Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership (Chicago), and The Ukrainian Museum (New York).

Celebrating its sixty-first year, Art at the Institute is the the visual arts programming division of The Ukrainian Institute of America, in New York. Since its establishment in 1955, Art at the Institute organizes projects and exhibitions with the aim of providing post-war and contemporary Ukrainian artists a platform for their creative output, presenting it to the broader public on New York’s Museum Mile. These heritage projects have included numerous exhibitions of traditional and contemporary art, and topical stagings that have become well-received landmark events.

***

Andrew Horodysky is a private art consultant with a specialty in Modern and Contemporary print culture. He is affiliated with the Association of Print Scholars, and serves as an advisor to Art at the Institute in New York.