Jerry Zeniuk: 10 Tips on How to Paint

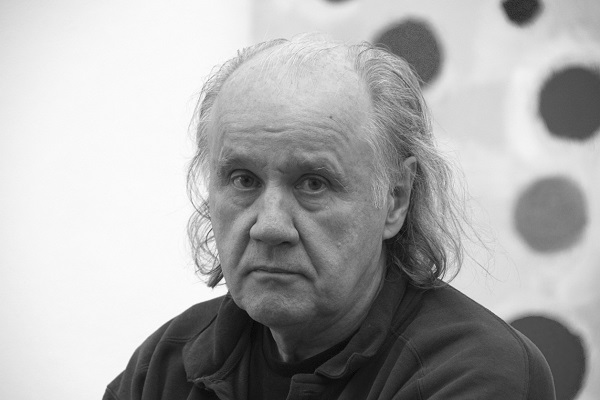

In the beginning of October, an open artistic conversation by well-known artists Jerry Zenyuk (Munich / New York) and Anatoly Kryvolap (Kyiv / Ukraine) took place at the ArtUkraine Gallery in Kyiv. In the wake of the event, we publish an excerpt from Jerry Zenyuk's book How to Paint, in which the artist substantiates the relevance of painting in the diverse and alluring world of contemporary art.

1

To look at a painting, to understand what you see, takes time. Since we look at images from before we can remember, we think we know how to look. Children don’t need lessons in seeing and do so naturally. But there comes a time when we realize that there is more to see than we are used to seeing. This desire to see more comes at different times in life and for many reasons. By the time we learn that there is something called Art, we know that we must look at it in a special way. Generally this occurs long before we visit a museum. Seeing in a museum is also learned. Sometimes, we learn to see more meaning in what we see; unfortunately, seeing with discrimination is becoming a lost art.

2

If you study painting, you see more. It is not that your eyes have gotten any better, rather it is because you have thought about and reflected on what you have seen. Seeing is a kind of visual thinking. How you think determines how you see. Painting is conceptual and can therefore express a broad spectrum of ideas, especially narrative ones, that use visual forms to illustrate ideas. But it is optically based painting that is least understood. When you step outside of language, you have less experience for expressing thoughts and judgments, and you fall back on narrative or literary thoughts. Painting that does not depend on narration or mimesis often needs an explanation or justification in order to grasp its meaning.

By Jerry Zeniuk

Courtesy of the Goethe-Institut Ukraine

3

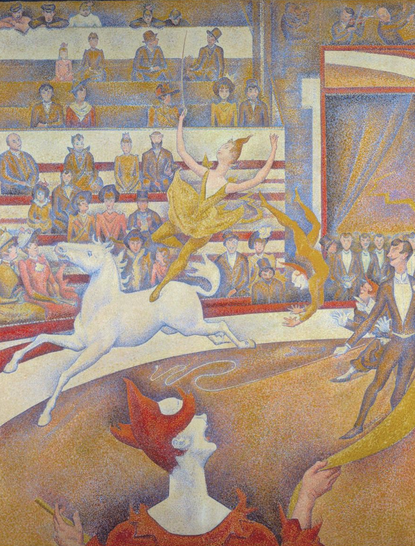

Visual artists, painters in particular, think outside the limitations of language. I would say the fullest explanation of their method is the understanding of space, whether it is actual space or pictorial space. Pictorial space is an imaginary space generally seen in pictures or paintings. Space has no time. Time comes from moving about in space. Pictorial space is quickly grasped, making for a static image, but moving about in this static space enhances the visual experience and takes place in time. So when we look at a picture, we see everything at once; but in real time we see much more, although the image has not changed. Space has no limits. Seeing the space, moving about in the space takes time and creates dimensions. Seeing is very different from language. Everything we see takes place in a space. This space has a light. We see the light in the objects that reflect it. And a painter, and in particular a color painter, sees the color of the light on a plane independent of the corporeal form. This transformation is what visual thinking concerns itself with in the creation of images. A painter sees and thinks about the organization of color on a plane that suggests a space. The picture plane is an imaginary plane corresponding to the surface of a picture and, in particular, a painting. The picture plane, and what takes place upon it, is where serendipity can occur. Color releases emotions, and the pictorial space is a non-judgmental place that frames and contains these emotions so they may give access to a universal understanding. A masterpiece never seems to have been painted, but rather to have always existed.

4

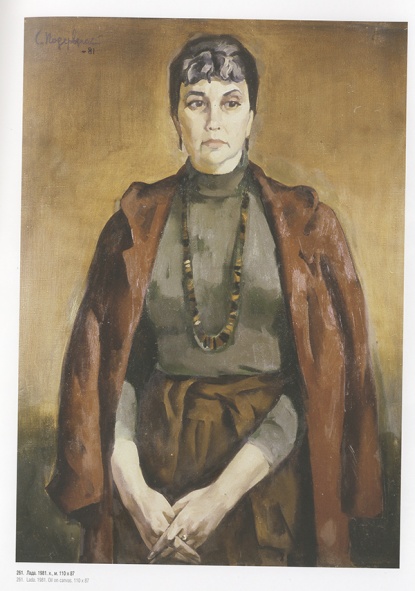

Individual portraits may be judged for their visual qualities rather than by the significance of the sitter. Nowadays, religious paintings or frescos are judged independent of their religious content. Similarly, historically themed paintings hang in museums because of their pictorial qualities and not their historical significance. Of course, still lifes or genre paintings are valued for their formal qualities since there is little significance to bananas, apples, or oranges. A universal aesthetic does not deny multiculturalism if it is based on formal qualities. It is, however, expected that such a visual aesthetic be distinct from cultural or philosophically based criteria. Formal qualities are universal.

5

If we look at a painting for its formal qualities, which qualities should we use to judge? By judge, I mean that we as viewers decide to devote more time or less time to looking and seeing a painting. We could accept paintings hanging in museums as the basis for establishing criteria. But even this is difficult to define. As viewers we come to accept the judgment exercised in museum collections, but what hangs in museums changes all the time. The distant past remains relatively fixed, but as we approach recent history, we see more changes. We say taste is always changing, even our view of the past. We reevaluate the past according to the present. We see the past through the present. But the present changes how we view the past and how we preserve it.

By Jerry Zeniuk

Courtesy of the Goethe-Institut Ukraine

6

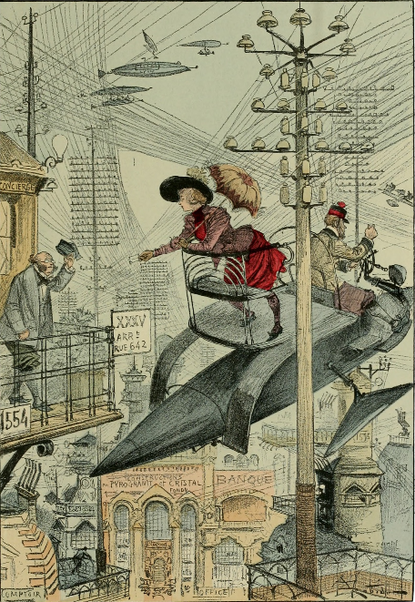

The past helps us to understand the present. When we are growing up, we are in the present and slowly learn about the past. The past is present in our culture, but it must be pointed out to us and learned. If you don’t see the past in the present, you are not looking deeply enough. We say the more cultivated you are, the more you are able to recognize the past in the present. Of course, the more knowledgeable you are about the past, the more it influences your view of the present. Thus as we grow older and more experienced, the new seems not so new.

By Jerry Zeniuk

Courtesy of the Goethe-Institut Ukraine

7

This is true only if you can connect the past to the present. Otherwise the present that we bring with us becomes nostalgia as we grow older. Thus art must be timeless and timely. It must be timely to remain relevant, and it must be timeless to be relevant as we grow older. If we substitute the word “fashionable” for “timely,” we would recognize fashion by its acceptance in society. And by definition, fashion is always changing. At some point in life we want something more permanent. We can call it truthful, or classic, or even timeless. When fashion achieves its highest level, we call it timeless. Nostalgia is the yearning for a past that is no longer present or timely.

8

If we want art today to be timeless, we have to understand the painting of the past. This assumes that we find painting relevant. It is not uncommon to encounter people who see painting as a minor art or irrelevant altogether. The very notion of what art could be and how it should function in our society is always changing. Maybe the most difficult task is to ask: To which art form shall we give our attention? By choosing painting, we can always go forwards and backwards.

Jerry Zeniuk

Courtesy of the Goethe-Institut Ukraine

9

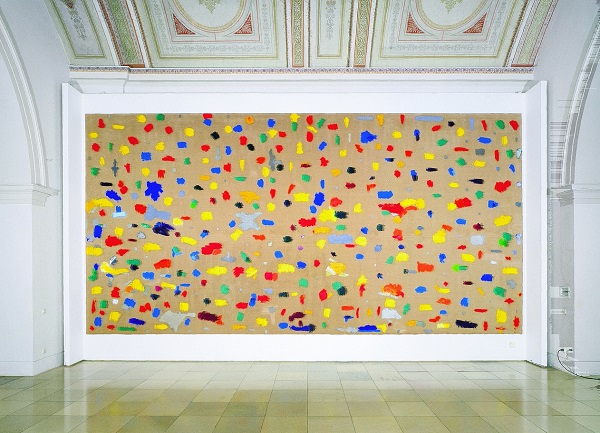

It is useful to define painting more precisely. Painting is something, but it is not everything. It is first, as Maurice Denis wrote in 1890, “A flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.”[1] This arrangement of color and lines refers to a flat plane and does not seek to be sculptural. In the last hundred years many painters have experimented with the limits of the plane that contains the image. In logic, something cannot be true and untrue at the same time. In painting, no matter how three-dimensional something is, it wants to be flat and planar—or it shifts into the realm of sculpture. It is the concept of painting that the resulting image is two-dimensional. When forms relate to each other as three-dimensional elements, the image becomes a relief or a sculpture. Images belong to all the arts, but how they are formed determines what we name them. Painting is true to the plane. Frank Stella’s painted reliefs want to be paintings. If they are seen as reliefs, they fail as paintings and do not succeed as sculpture. This is because they were conceived as paintings. His experiments in painting have been interesting to follow.

By Jerry Zeniuk

Courtesy of the Goethe-Institut Ukraine

10

From the time of cave painting, artists have tried to create three dimensions on a flat plane. Pictorial space, the illusionary space created in two dimensions, is an essential visual concept inherent in painting. Even when a painting is conceived as paint on a flat plane without any suggestion of depth, the viewer, through recognition of the picture plane and the modulation of the surface, sees depth. The pictorial space that the image evokes in contrast to the surface tension is the essence of all painting. The way you understand this relationship allows you to formulate criteria that allow for judgment and the allocation of aesthetic value.

[1] “Se rappeler qu’un tableau, avant d’être un cheval de bataille, une femme nue ou une quelconque anecdote, est essentiellement une surface plane recouverte de couleurs en un certain ordre assemblées”. Maurice Denis, in Art et Critique, 1890