Anatoliy Kryvolap: “An artist should be recognized by his works, and not by his appearance.”

It is best to ‘get to know’ the works or Anatoliy Kryvolap – one of the most interesting representatives of contemporary Ukrainian non-figurative painting – in his studio, located in a picturesque village not far from Yagotyn.

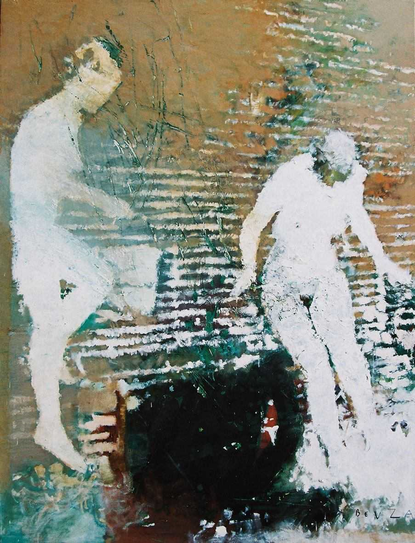

Cloud

Article from ART UKRAINE #5 (24) 2011, September-October.

We came to visit the artist on a hot summer’s day and were very quick to notice the contrast with the hot buzzing city: just a 100 km from Kyiv, a beautiful view, birds hovering over a lake, a cozy living-room and a pleasant conversation... This is the eco-system that Kryvolap’s works are born into, and here you right away understand the inspiration behind the artist’s latest series. This is the window through which he watches the sunset, these are the houses, cattle and other elements of the rustic pastoral that make their way onto the canvas.

Kryvolap was trained as an academic painter but has since a long time turned to abstraction. Several years ago he again started introducing realist elements into his works and today, balancing on the line with abstraction, he produces meditative landscapes in characteristic hot color-scheme.

Anatoliy Kryvolap. Photo: Maksim Belousov

A very bold use of ‘active’, self-sufficient pigments is a signature element of Anatoliy Kryvolap’s work. His color intuition is very close to a traditional one – we see such combinations in traditional costume, decor, and naive art. Among dozens of finished and unfinished works from different years Kryvolap also has several traditional beddings lying around: their bold stripes probably give him inspiration and help stay grounded among many imported ‘-isms’. Modernism, abstractionism, anything - a contemporary artists can’t escape the claws of ‘branding’ that the world is constantly imposing. But the idea of a genetic code lies beyond any type of branding and it is this idea that Kryvolap is so transmitting onto his canvases.

At sundown

He is one of the most successful Ukrainian painters, his work is admired, loved and collected by many. His canvases go for record prices at world’s most important auctions and art-fairs, he has shown in all of Ukraine’s biggest museums and galleries. And yet the artists strikes with his humility – no just in his everyday life and surroundings (where he is far from being extravagant) but also in his art. Anatoliy Kryvolap is not one of those artists who make a name for themselves through something else rather than their art. He rarely goes to social events or even art-gatherings. Far behind are the early 90s when the artist, together with other masters of Ukrainian non-figuratism – Tiberiy Silvashi, Oleksandr Zhivotkov, Mikola Babak, Mikola Krivenko, Mark Geik - was part of modernist ‘Artistic reserve’ group and heatedly discussed the future of Ukrainian contemporary art. He is still friends with ‘Reserve’s’ ex-members, but when it comes to his art he chose to take his own way. At the same time his interest towards the problems of art evolution and towards contemporary state of things in the Ukrainian art-scene is still alive. In March 2011 (at ARTUkraine’s website) Kryvolap published his manifesto where expressed his dissatisfaction with the current situation in contemporary art. This publication became one of the most-visited pages of our online-version and obviously aroused a lot of public interest. So now we are offering you a continuation of our dialogue with the ‘living classic’.

March

— Today you are rightfully called a classic of Ukrainian visual art. What triggered your interest in painting?

— It must have been mere chance. I was born in Yagotyn, it was right after the war, there were no roads, no radio, no TV. When autumn came and it started getting dark at 5 PM - there was nothing to do. But we, the kids, didn’t feel like going to bed. And so I started drawing. I always though that I started when i was about 10, but then my mother told me that I would draw pictures of miniature horses from the very early age. And I got so into it that I lost interest in everything else.

— So you did start with figurative painting. When did you take abstraction up?

— Oh, that’s a long story. I was about 20 when I first found out that there is such a movement called ‘abstraction’, some picture from some catalogue just stuck in my head. Before that I though that I would be a great colorist like Serov, and in art school I specifically asked for Viktor Puzyrkov to be my tutor because he was the only truly academic instructor. That is, I did everything to avoid being interested in abstract art. But I guess you can’t escape yourself.

Evening field

— And when did you start experimenting with non-figurative art?

— I think you can say that I was kind of doing it all the time. I was first seriously exposed to art when I did military service in Riga in 1965-1967. Even though I was in the army I still had a chance to go and see shows, and, unlike in Ukraine, the Baltic States did no suffer form censorship to the degree that Ukraine did at that time: you could see anything there, even abstraction. And so having come back to Kyiv I focused my education on experimenting with color. Even when I was making an academic piece I was somehow very dissatisfied and I couldn’t figure out why. Although, I knew that something was wrong.

It took me 20 years to finally find myself. I worked as if in a laboratory, kept diaries, experimented. I had a serious problem with harmonizing bright colors and I tried and tried to solve it. I tried all kinds of standard painting techniques and laws, like using more white or adding more ‘dirty’ shades. But in order to harmonize primary colors that are almost screaming with tint I needed to find some unconventional approach. I was always fascinated with bright colors but it was first really hard to work with them. It required effort.

Sundown at the lake

— It must have been a very tough experience and required a lot of courage...

— I don’t’ think it was courage, I just had no choice. I always knew that creative process is like flying, but I couldn’t fly until I found my own way. Naive, traditional art, especially Ukrainian, has an intuition for color. You very often find combinations of open, bright tones in it. I was always surprised why academic painters, having such a gold-mine of color and inspiration as traditional culture, kept their pallets so scarce and pale.

— Despite such an obvious connection to traditional culture you are one of the pioneers of contemporary art in Ukraine; the ‘Artistic Reserve’ group, which you were part of, used to be the forerunner of Post-Soviet contemporary art in the 90s having pushed back social-realism. What made you choose this path?

— I was never a soviet artist. I graduated from art school, in two years was done with my work for the Artists Union. By that time I had already shown my work in three national–scale exhibitions. That was a huge deal! They asked me to join the Young Artists Union but I refused.

Lake. Morning

— What were you doing all that time?

— Experimenting. Tried to take my work onto a new path, take new steps. There were no revolutions in my work, there was only evolution.

— In the rest of the world the interest towards non-figuratism was characteristic of Modernism. Then things went further. By the time you were completely engaged in abstraction Europe was already looking towards Postmodernism. Did you feel shocked or traumatized, just like many of the humanitarian inteligentsia did, when the Soviet Union collapsed?

— I think that art is a selfish thing and everyone has to live through his or hers fate with it just as it is. I was always so absorbed in my own relationship with color that I wasn’t even very interested in all the movements. Just think of how many times there was talk about art being dead, – and it is still alive! And as long as there is paint and people born to communicate their inner being through this paint, there will be painting. All those artists that gave up painting in the early 90s and started playing with photo and video very quickly came back to paints and brushes.

Near a lake

— Were you interested in experimenting with new media?

— For about twenty years I observed these new media, went to shows. But this kind of art doesn’t stir anything inside me. I think there are several types of artists. There are those that have great imagination, they make up new worlds, make complicated structures. Some are more keen on acting, pr, some see some new exciting technology and some are good at making fun. But if your best way of speaking is through painting then there is no reason why you would give it up. Although it is true that new time requires new form.

— Are you an active cultural tourist? Do you often go abroad, visit shows?

— A moderate. I don’t really have the need to do it. I think you should absorb as much information as possible when you’re young. Later on it’s about focusing on oneself.

Laki. Moon rising

— You have recently become Ukraine’s ‘most expensive’ artist. Your works are in the National Museum of Art, in other important collections. This means that you have a successful career. Do you feel important?

— I am a kind of person who constantly doubts, so – no. As for me being ‘expensive’ – well, my works have been among the most expensive (in Ukrainian market) ever since 1990. From that time on I only raised my prices. Already in 1992 I had a deal in Germany where I sold a work for DEM 11 000. When I came back to Kyiv, local artists were selling their works for USD 200, and my works by that time were already worth thousands.

— And were do you sell most of your works to today? Do you work for a local or a Western collector?

— For the first 15 years i didn’t have any clients here, in Ukraine. But in the last 5 years most of my collectors are Ukrainian.

Evening shore

— Are you tired of attending all these shows that your works are part of?

— I never go to my own openings. To go through an opening is like torture for me. I was always sure that a painter should be recognized by his works, and not by his face.

— How fast do you work? Are you able to satisfy the demand for your works? I know that for many top art market artists it is a problem because the speed they work at does not coincide with demand. There could be a waiting list for years to come.

— These are all special techniques. Such cases are usually artificial: it doesn’t mean that an artist doesn’t have works. I know cases when an artist was told not to paint in order to make his work more expensive.

As for me, sometimes a canvas can wait for years and another time – a huge work can come to life in an hour. It has nothing to do with my desire or will, not with demand. It is mere chance.

Ukrainian motif. House

— Do you keep track of events in Ukrainian art-scene, its development, new generations?

— Of course. But I am more of an observer. I just anticipate.

— So you haven’t found similar minds among your younger colleagues?

— I would have loved to, but haven’t so far. Contemporary art is an extremely vast and broad phenomena, but even in the broadness I haven’t’ so far found any interesting solutions. As for the shows – contemporary art should, after all, have some connection to life, and if there is no such connection then it turns into a game.

Polonyna in the Carpathians

— Do you find the ‘group’ type of creative thinking an interesting one?

— No, I think this is a thing of the past. As a person I have a lot of friends and relations, but not as an artist... In the early 90s there was a time when we, the Artistic Reserve were very much inspired by this creative dialogue. But then we parted ways.

— In the Western model, when an artist has achieved a certain degree of fame, a certain age, he starts teaching. Do you teach anywhere?

— I tried. I even tutored several artists and you can recognize them through their use of color. But it looked like cloning and I realized that I myself started doing not exactly what I wanted to and decided to stop all these experiments.

Evening at the lake

— But someone has to teach...

— Mediocre artists have to teach. They can give the base and then the person has to figure things out on his/her own. Appropriating someone creative vision is the easiest thing, but you will never become a great artist. That’s why I see no reason in teaching. Those with strong creative minds will survive by themselves, will find their own language. Artistic language is a code. A painter makes codes through images, a poet – through words. It is feelings and thought that are coded, but not ideas. Ideas should be in science, in philosophy, there you have discoveries. I don’t know a single artist who would be a philosopher.

— How interested are you in art history? With whom of the artists do you see yourself communicating through time or space?

— This is a typical thing for artists: you have to go through almost the entire history of art in order to find yourself. I had an ideal at every stage.

— What are your thoughts and feelings today? What inspires you?

— I came back to somewhat of an ‘outsider’ genre: landscape. Landscape caused both revolution and evolution in art, but in the XX century it was pushed to the end of the list of subject matters. I used to ‘keep my shape’ by making landscapes, etudes, and lately realized that I am interested in turning this into a bigger project.

— Was it long ago that this happened?

— I have been painting landscapes all my life. Even when I made abstract works I still did it, even in the 90s. Then I realized that I can’t go further than a Ukrainian motif and so focused on abstraction which opened up new horizons, new experiences. But when I moved out here, into the countryside, then I really felt the urge for something really Ukrainian, even Gogol-like. And so I consciously came back to landscapes.

— Your landscapes are on the verge with complete abstraction. Sometimes you can’t even guess if it is one or the other.

— Yes, I stay true to abstraction. I think that so far this is the most interesting thing that humanity came up with when it comes to art.

— A characteristic feature of your work is this violent purple color, a mix or red-blue-purple... Is this a tribute to sunset or just a reflection of a specific inner state?

— I is an emotional state. I don’t just create landscapes, I create emotional space.

— What does this color mean to you?

— I guess it is something beyond time. Since early childhood I can’t really feel time. I never think of reality ‘the way it is’. I see it through personal emotional states.

— Aren’t you afraid that you won’t be able to keep up with time? To miss out on something important?

— ‘Contemporary’, as an artistic movement, seems to me a kind of marathon – people from all over the world get together and run, rush somewhere, but it is all a short-term thing. Today the marathon is in Sydney, tomorrow – in Germany. Just take a look at how quickly all these movements die out. Art is like a vessel following its course, and around it there are smaller ships and lifeboats. Is art you have to go with your feelings, your thoughts, your own worlds. Otherwise you are just taking part in some stupid marathon. I don’t find that interesting.

— And what is there when time stands still?

— In one catalogue entry I wrote that silence is a meeting point of the Eternal and the Mundane. I think this would answer your question. This sun and this grass were here two, three thousand years ago and already then artists used these subjects in their works. But we all see the same things – everything in this world is stable. Only interests, perceptions and attitudes change. Everyone has to find his own way.

— You have such an introverted view on art. Is that an influence of religion? Are you a believer?

— I don’t go too deep into these things. It is very intimate. All my life I have been working with paints and colors and the processes connected to this can really make a believer out of anyone. I was very self-confident when I started out, – I thought it was easy to do what I wanted to. But no matter how much I tried I always failed. This lasted up until the moment when some switch inside me just flicked, and then instead of using gray where ‘it was supposed to be used’, I started using yellow, or blue, or red... I can teach harmony even to a bear, but it doesn’t mean that it will become a painter. I am just a pipe – when something goes through me I put it on canvas. This must the happiest of states, too bad that these moments are rare.

— You live in a beautiful house in the nature, you love your work. What else are you interested in, what is your life except painting? Are you interested, say, in politics?

— Just as every human being I see things around me but because of my crazy disposition I can’t let myself get too involved in them, because I simply wouldn’t be able to work. I think that the best political statement is to do your job right.

— “The world tried to catch me, but failed” wrote Skovoroda...

— I guess that is right. I lived my life with my work and all my interest was always in it. Everything external – that’s about 10% of my life. I didn’t even notice my children growing up, time going by.

— Did your children follow in your footsteps? Did they become artists?

— My daughter – yes. My son is a machinery expert, just like my father. My daughter has been drawing since she was a little kid, she is very talanted. What I got through work and experimenting – my color-work, - she has inherited naturally. If it’s good or bad – time will tell. Because obstacles are what makes an artist. You give up or become stronger, build your character. This is what is required for an artistic vision.

Alisa Lozhkina