Arsen Savadov: “My characters are personalities with a vague understanding of reality”

One of the brightest stars artist of Ukrainian contemporary art needs no introduction. In a conversation with ART UKRAINE’s editor-in-chief, Arsen Savadov tells about important works from different years, about his relationship with conceptualism and the reasons he decided to come back to painting.

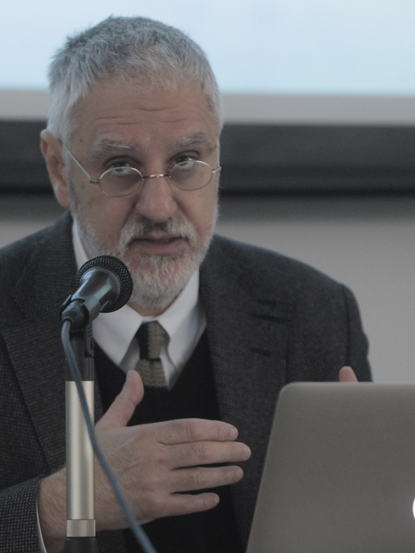

Arsen Savadov. Photo by Maksim Belousov

Article from ART UKRAINE #1(1) 2011 September-October

— Yes. The piece was first conceived as a biblical scene. It is part of a bigger cycle of works: with it I finish working with a certain list of characters – and they were the ones that I sent off to Egypt. In this scene, which has the esthetics of a Brazilian carnival to it, the characters – an entire culture – are escaping the world which surrounds us. It was a mere coincidence that the show at Kollektsia gallery, were I first presented these works, coincided with the events in North Africa. I wrote the catalogue entry together with my usual co-author Georgii Senchenko, – it was his idea to tie each work to a strong social context. As for me, I simply like the idea of escaping from Herod to a world of a lighter substance, to a certain future. I think the dynamics of movement is something that is of great importance for a painter. As an average decadent, I use this dynamics very consciously when building my psychedelic paths and send my characters of to, say, Egypt. During the actual biblical scene Mary was trying to save a cultural substance, and here we are saving that exact spiritual power which finds it hard to exist together with the contemporary world.

— Your works are usually kind of ironic, postmodern, although today it is somewhat vulgar to use this term. In a way, postmodern is followed by a new kind of sincerity. So are you characters yesterday’s postmodernists escaping to Egypt from the totality of this century’s seriousness?

— Not so much from seriousness as from total distaste. Many things and objects, that require a deeper analysis, have passed away from us. And we are left within a society of a provincial town, with Kyiv itself turning into one. The city lacks the traditions that it once had, the writers, artists, the ‘intelligentsia’, - it is all dying out, drinking itself to death. The same is happening in London and New York: ‘new’ people can’t afford paying rent and thus live in the suburbs, pushing the ‘Metropolis’ to loose what it actually exists for. It’s not that my characters have simply exhausted their potential, - they simply couldn’t fit into the presented context. It’s like hippies who left England years ago, and having come back encountered the society of Margaret Thatcher and yuppies. So they left forever.

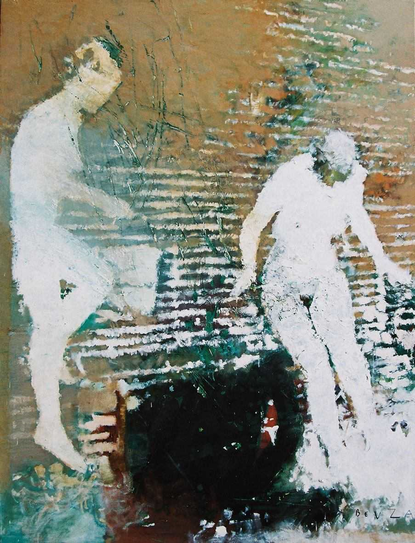

Arsen Savadov and Yuri Senchenko. Cleopatra's Sadness. 1987

— So if needed you can just send your characters off to Egypt forever...

— Frankly, they don’t care where I send them. They go by themselves.

— And where do the real people go from this dominance of vulgarity?

— In the top part of the work there is a sort of a divine brush drawing a red line which all the characters follow. As a rule, when I am working on a piece, I enter a sort of trance, I see things. Behind that red line there was a stop sign: that was all that I saw.

Arsen Savadov and Georgii Senchenko. Black monkeys. 1991

— Your characters, who are they?

— Naturally, they are the symbolic Adam and Eve, they withstand very serious temptations (it’s not by chance that there is a lifebuoy in the piece)… They are holding a light-bulb which they can’t let go off, and as a result you have the Holy Trinity. Along with that you have the clothespin, one of the recognized symbols of Pop Art. My characters have a blurry understanding of reality and a washed out sexuality. It’s a mob, a rabble that escapes the Soviet government in search of a better life. Their departure is a celebration, or, maybe, – a funeral.

— You are speaking of freedom, psychedelics, sex. But, on the contrary, for the generation growing up after the fall of USSR there is a problem of permissiveness: since their childhood they can do whatever – watch porn, have sex... thus we have a generation of ‘new dopeys’. How do we deal with such people? Do you consider them your audience and would they be able to understand those symbols that you implement in your works?

— Of course they can. They are, after all, ‘dopeys’, and opposites attract. I have a big fan-base, which is all so muddled-confused, they look at Shahtari and get so touched by it that they become artists. Actually anyone who gets to meet me becomes an artist for some time. Really, this is a time of forcelessness! Who’s going to defend the world when half of the world is gay? The strong male gene, which could be juxtaposed with all of these new Muslims, these Saladins, is gone. It’s impossible to get an army of barbarians together today.

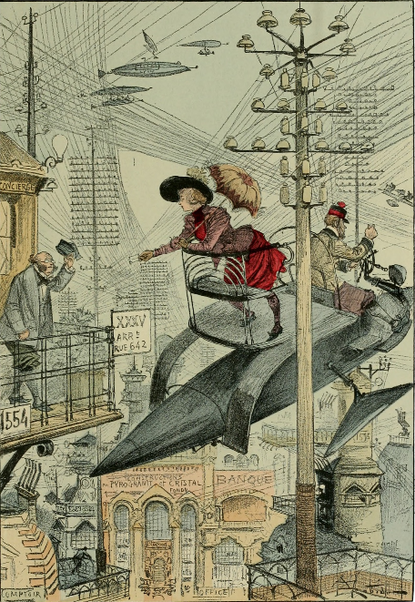

Arsen Savadov. Satelite. 2002

— The Western culture has exposed Eros to the extent that it became uninteresting and has his Tanatos to deep that it became unnoticeable...

— I am one of those artists that treat the harsh conditions of the day as myth: I make my work out of the rubble of consciousness. And as for the young generation’s reception of my work – I ‘test’ it out on my nephew. He doesn’t see any trace of the postmodern in this kind of sensibility, for him it is real emotion. He is interested in the painting itself, as in a non-synthetic, organic product. Apart form characters, a painting also has oxygen. He managed to catch this because he understands how this painting is different from a computer-screen, which, on the contrary, does not give one ability to breath. My world is full of objects and symbols, and this is what fascinates him.

— Is it because of this feeling of fullness and demand that you lately focused more on paining than photography?

— Yes. I think it’s a logical step of evolution. Sometime in the 90s I realized that I was bored with painting. I started working with new media, not just photography; I made huge banners, videos... It was inherent to that time because we were going through this stage of our development. We didn’t go to some art or painting school, but dived into Moscow conceptualism and liked it! But with time it became clear that we have to look for our own path.

Arsen Savadov and Georgii Senchenko. Voices of Love. Film stills

— Conceptualism is in itself cold and logocentric. You, on the contrary, have never been ‘cold’...

— We are talking here about the mechanics of conceptualism and not about the final outcome. Conceptualism is a systematic thing, a decedent culture in the framework of which one should always have an opponent the work of which you are taking a stand against.

— Whom of the conceptualists do you find close at heart?

— All of them. From Kabakov to Monastyrsky. I respect the work of Pavel Pepperstein, always admired Sergei Anufriev, Yuri Leiderman: because of their cultural intuition they are way ahead of all the other artists that I know of.

Arsen Savadov. 'Donbass-Chocolate' series. 1997

— As much as I understand, from the reaction to your and Senchenko’s show in Moscow in The Central House of Artists (1991), the public and critics saw you as the opposition to conceptualism and got scared of the mighty wild ‘south-Russian wave’…

— The period of several years before the fall of the USSR, somewhere between 1987-1991, was the sweetest. We got new literature, everything became legal.... Of course the Moscow audience was surprised by my appearing in the scene. These were people from ‘The Capital’, they thought they knew everything and everyone around, and there you have it – a new culture, a new technique, and most importantly – we were open to change and indeed did change quite quickly by being receptive to the trends of the time. But we also keept our uniqueness. They still tell me how they love to be around our paintings, how they got incredibly high next to them. Cleopatra was a particular success there for many years to come.

— Speaking of the famous Cleopatra’s Sadness (1987). It is a sort of a ‘phantom pain’ of Ukrainian art: everyone’s heard of it, named it the starting point of contemporary Ukrainian art, but, at the same time, only the lucky ones have seen it...

— Well, that is how it is today, but back in the USSR, though, this work was exhibited many times and caused a lot of commotion. You could still feel it in 1991. We were saved by the collapse of the Soviet Union: the ‘Pravda’ newspaper has already labeled us fascists because of that work.

Arsen Savadov. 'Donbass-Chocoolate' series. 1997

— It must be the one and only local masterpiece created in the post-masterpiece times...

— It was fantastically made! Even if you mention its dadaism it is still a ‘bombshell’ of a work, Arman, who bought the work, is no idiot! FIAC, where he acquired the piece, is a very serious fair, and even in Moscow, in the Manege, it was the only work which had a frame made for it (even though its dimensions are 3,30x2,75m). This canonicity, the fact that we managed to lose our conceptual dryness, ideology – this is what is important. Most of Ukrainian visual artists think first of all about emotions and only after that about the content. We had a ‘cold’ work created in the framework of ‘hot’ aesthetics, moreover – made with pentaphthalic paint. All in all, despite it s appropriationalist nature, Cleopatra was a very organic work and people saw the real new art in it.

— Do you think there is a chance that it would come back to Ukraine? And, most importantly, would it make sense?

— No, there isn’t. We were always against it. Cleopatra wasn’t created for contemporary Ukraine. And if you bring it back here people are going to think: “What’s so special about it?”. Yes, it is an important work, it inspired many artists to join this style. When they saw how I painted the hair on the tiger’s belly – behind all the conceptualism and coldness there is a lot of aestheticism, - many were shocked. Anyway, there is no Cleopatra without the Soviet Union.

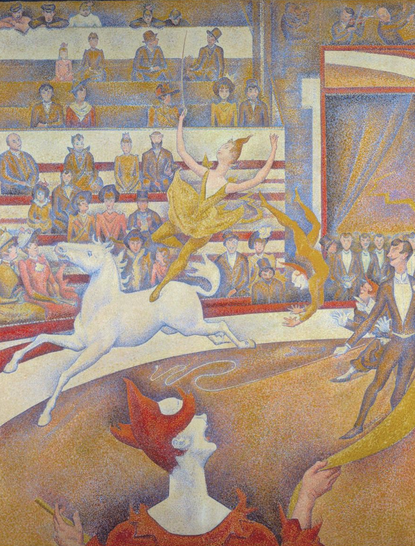

Arsen Savadov. 'Angels' series. 2000

— Soviet culture stressed the importance of reading. Does it have any meaning for you now? Are you reading anything?

— I am currently rereading Fritjof Kapra’s The Tao of Phisycs, from 1979, a very serious book. I have a big library but I am generally not a fan of fiction. I prefer ‘serious’ literature – philosophy, religion. But today we are experiencing a crisis of philosophy and I don’t feel like rereading the same old Baudrillard again? I also enjoy Bulgakov – his Russian is exclusive!

— After Cleopatra your next slap on the society’s face was Shahtari (Coalminers)

— This was the peak of provocation. But before that came the powerful ‘Voices of Love’ video in 1994, a collaboration with Georgii Senchenko. We dressed an entire military unit of the ‘Slavutych’ ship and made a remake of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. It is a very powerful, almost 1,5 hour-long video.

Arsen Savadov. 'Donbass-Chocolate' series. 1997

— The poetics of ‘members-only’ gentlemen clubs, ballet tutus, the element of absurdity – is that the mythology that later on becomes apparent in Shahtari?

— Naturally, it’s the work of the same psychedelic agent, a sort of Dadaism, art out of nothing, from a children’s book. I myself, when I have to print out the shots in big format, am shocked to see what is going on in the frame. I am speaking now as a consumer, I don’t even realize that this is my own work. The digital prints – they come to life, the shadows in them come to life, and I think to myself: “Wow, did this really happen to me?”

— These were projects that caused a lot of outrage. The interesting thing is that most of them were printed in fashion magazines in Moscow. This was the time when you collaborated quite closely with such publications...

— My friend Igor Grigoriev was the editor-in-chief of a local Moscow magazine ‘HOMME’ at that time. But the fact that my works were published there had nothing to do with our friendship. If it would have been a different work, something that he, as an editor, wouldn’t approve off, he wouldn’t have published it. But when he saw my work Shahtari, and then Trend for Cemeter’ (Мода на цвинтар) he, just like Olga Sviblova (Russian curator and director), just wouldn’t let me go. I showed Shahtari once at the New Manege, right next to the Kremlin, and Marat Guelman (Guelman's Contemporary Art Gallery) took them right away and put them in his office. Afterwards, by the way, he presented them to The Russian Museum.

Arsen Savadov. 'Book of the Dead' series. 2001

— Why don’t you show Voices of Love, the work that you just mentioned? I only heard about it but haven’t seen it anywhere lately...

— Voices were everywhere – at Ars Electronica in Austria, at a contemporary art show in Finland, in Moscow. It’s just that it was a long time ago.

— The lack of memory is very characteristic of Ukraine. We sort of have everything, but in 10 years no one can remember it...

— Yes. It is different in the West, in the States. There everything is thoroughly documented, and we, unfortunately, just play some games. it’s a big lethal game where only the strongest work survives.

Arsen Savadov. 'Book of the Dead' series. 2001

— Your works will probably survive...

— When I began making photos, videos, big projects that were innovative for that time, hardly anyone was around. There was, of course, the Artists’ Union, the Ministry of Culture, Tiberi Silvashi, that’s it. There were no computers, no service: I had to go to Belarus in order to print out a banner. Those were all in a way acts of courage and we just got tired of committing them at some point. We self-funded shows and some people managed to get some degree of social memory from them. Indeed it helped our careers, but on a day-to-day basis, until the start of craze for painting works, we were all very poor and did everything out of our own pocket. I would rent out flats to people, get the money for that and fund projects. I didn’t spend money on a flat on the Crimean coast, but gave everything to Angels, Shahtari and other projects.

— How many photo-shoots did you make?

— A lot, about twelve, I think. I would always work as a composer, but today my medium is painting – something I love and know how to do.

Arsen Savadov. 'Book of the Dead' series. 2001

— Coming back to painting. Why do you think the Leipzig school became a renown phenomena in the art world, and the Ukrainian ‘New Wave’, not less powerful and unique than the first one, remained and still remains a local thing?

— We simply didn’t get that much attention...

— Do you consider Neo Rauch as your vis-a-vis?

— I long since lost this duel. He’s worth a million, and me – $ 100 000 max.

Arsen Savadov. 'Collective Red' series. Part 1. 1998

— Do you feel intimidated because of this?

— In a way, yes.

— But you are a world-class painter...

— Yes, and I am sitting in a corner.

Arsen Savadov. 'Collective Red' series. Part 1. 1998

— Do you think there is still a chance for the ‘New Wave’ to become go out onto an international level?

— Well, we are not dead yet... And I am sure we will age just like good wine does.

— Do you see yourself as a Ukrainian artist?

— I am a person whose establishment happened in the years of the USSR, I represented that country. Of course, the division that happened in 1991 was and is for me absolutely disadvantageous.

Arsen Savadov. 'Collective Red' series. Part 1. 1998

— Yes we were all born in a big and powerful country and die in a small third world state...

— Either in 1991 or 1993, don’t remember exactly, Georgii Senchenko and me had a hour-long broadcast after the Vremia show. And we had shows in New York. Today, naturally, since I didn’t immigrate and stayed here, we are trying to play the Ukrainian card. I was born in Kyiv around the Shevchenko district and for many years now haven’t left it.

— A lot of people are still shocked by your Book of the Dead. It is a very complex work.

— When I visited Afryka (real name Sergei Bugaev, Russian artist) several months ago he told me that he is still shocked, too. He gave me a book of Tibet texts about afterlife, a very interesting work: with this he again raised the topic of the Book of the Dead.

Arsen Savadov. Myrrh-Streamers. 2010

— It is quite interesting that a work, made around 2000, seems ever more up-to-date today...

— I think that some topics and subjects should be closed, done with in order not to let them be abused by those who lack talent. Shahtari, as a subject, also had to be let go of. The same with the morgue: I saw how my assistants, having entered its space and not having understood much, would start just snapping shots of everything, - they were simply going ecstatic from the amount of death and disgust around them... This kind of topic, though, should only be addressed once there is a certain system to it. Otherwise you get complete nonsense: meaningless shots of something by someone. I once got my hands on an issue of Stern magazine from 1998 where I found an overview of contemporary, to that time, Russia. Five photos: on one – a girl being abused somewhere around the Kyiv train station, some other nonsense, and in the last one – a hospital: a pile of corpses, all so thin and creepy, and the one on the very top has eyes drawn with a pen on his thigh. And then I understood: this topic is finished, done. For the people who worked with me there the morgue came to be a very difficult experience, but they handled it well.

— Do you take pictures yourself or do you work with a photographer?

— I have a photographer. I myself just make up the composition. I can take pictures because I think I would then give up painting painting, and I simply can’t let that happen. And the photographer, on the other hand, is happy to work with me, - I guess what we do is better than taking passport pictures of strangers.

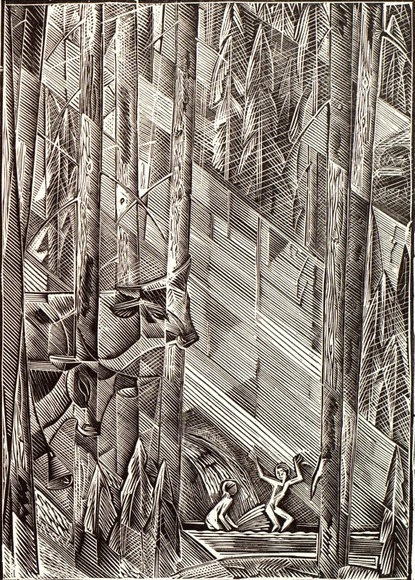

Arsen Savadov. Homage to Andō Hiroshige. 2011

— How do you manage to engage people?

— It’s all charisma.

— You are always surrounded by friends and supporters. What is the secret of your popularity?

— I am surrounded by great personalities; this is my own Karabas Barabas Theater. When I finish a painting it is really important to have someone next to me because I tend to become very inattentive – I can, for example, get run over by a car, - and that’s actually one of the reasons why I don’t drive. The foundation of my surroundings can be described as a certain type of rhetoric which is sometimes shaped by eastern cultures or conceptualism. People want to communicate with me because they tend to then get answers to the questions in the fields where I can be considered an expert, that is – aesthetics. It is this rhetoric and the clarity of thinking which probably attracts them. In art you have to open yourself, and this is the hardest part. You can’t be fooling everyone.

Arsen Savadov. Star. 2011

— Are you happy with your present-day type of artistic expression?

— Of course I am not, and that is the beauty of it. It’s impossible to re-do Shahtari, although maybe Suputnyk (Satelite) is somewhat an attempt to do that.

— Let’s go back to the Book of the Dead...

— The book is based on the above-mentioned magazine story, but I had to come up with one more narrative to provoke the discussion about what is reality today. The poststructuralist circles that we were part of at that time were slowly suffocating: Guattari was dead, Deleuze committed suicide by jumping out of a window. People were all having dreams about American industry and over-production. In 1991 Jeff Koons f***ed the simulacra itself – Chiccolina... No one was expecting that! And then Brenner tried to copy that and won his wife right next to the Pushkin monument. But this was all secondary material. I was living in New York for a while and when I came back I started and successfully completed three projects right away. And everyone was impressed! Because what I was doing was real. Only I could sneak Dadaism in, through girls, through dead, and later on – through quasi-academic painting. Yokels are afraid of realism.

It was in this context that all the talk about morgue, about anthropology, about morgue being the Final Destination of Civic Registration started. We are not just making a provocative photo-shoot – we are creating a sort of a new mythology.

— Do you find it necessary to be understood by ‘yokels’?

— It is, after all, the world we live in.

— How did you manage to get permission to shoot in the morgue?

— I found a very important person, who could push the right buttons to make this happen, explained what I want to do and that this is a type of renaissance tradition. And that man got me permission to shoot. Although for me the project wasn’t ‘on’ until the Book of the Dead came to be a performance, and this happened only when I decided to show it at ART MOSCOW in a context of things that were actually used during the filming process: carpets, tables, TV, other stuff. I wanted the viewer to sit in that chair which in the morgue was occupied by the grandpa and his grandson. And when he or she sat down in that chair and started flipping through the photographs, the realization of what this object actually is made the person jump out of the chair fasted than lightning. Now this is what I call ‘interactive’! And then I was asked to remove these works, the section was closed off and a guard (and old grandma) was put at the entrance with a sign saying ‘No entry for those under 16’. Naturally, this made the whole thing even more intriguing. No one expected something like this from me, no one thought I would go beyond photography. This was clarity of vision through fear, this was pure performance.

— Do you feel change in your work?

— I came back to what is really important.

— That is, having gone back to painting you have come back home?

— I have a different feeling. I think that very soon this entire pretty little world will be faced with the question of reality. The level of fame that our mafia of the 90s managed to achieve was never even imagined by any of the artists! Picasso and Dali dared not even dream of it. Mafia pushed everything back and then was replaced by Islam and terrorists. Hence in order to bring the previous level of recognition back to art we need a Book of the Dead. This is the only way one can work with the contemporary viewer.

Alisa Lozhkina