David Elliott: “The Past is a Prison”

Englishman David Elliott considers Manchester to be his home but, in fact he is citizen of the world: every week of his life is filled with an enormous number of flights and intensive co-operation with different art institutions. David’s record of service includes a 20-year long supervision of the Modern Art Museum in Oxford, a director post in Moderna Museet (Stockholm) and Mori Art Museum (Tokyo), Sydney 17-th modern art biennale monitoring etc.

In Kyiv, David is occupied with a very difficult and responsible task – to supervise the First Kyiv International Biennale of modern art ARSENALE 2012.

David Elliott. Photo: Maksim Belousov

ART UKRAINE № 3(28) May-June 2012. Heading FOREGROUND

Asya Bazdyreva According to the concept of the Biennale, the main project consists of four parts which represent different ideas. What was your initial impulse in organising the project in this way?

David Elliott These ideas - which I call hub ideas - are a starting point for thinking about the exhibition, about how it relates to the world at large and also to Ukraine and the region. They also express what I think are the effective areas that contemporary art is often busy with and which relate to the title of the exhibition The best of times, The worst of times. This title implies an historical density as well as a strongly aesthetic and philosophical concern. For me, these ideas are not really categories that would divide the show into sections. You can find them to a greater or lesser extent in all the works in the exhibition.

- In your statement, you say that “contemporary art and aesthetics use the past to represent the future”. Tell us more about this.

- This can seem quite a banal thing to say, but in the art world, with its fantasy of constant invention, it is often not regarded as a truism. This is really a modernist fantasy: each generation supersedes the one that came before and, in a sense, 'conquers' it, following the model of some outdated idea of progress which is, in fact, completely ridiculous. But this is the fantasy I grew up with and on which the contemporary art market, to an extent, still depends. I am making the very simple point that anyone can see in people’s lives or their art. The past can be a prison in that it confines the ways one looks at the present and prevents an open view of the future. But, if you are prepared to learn from the past and have a critical and creative relationship with it, it can also be a platform for doing something much better. No one is a tabula rasa, not even when you are an infant. So the real question is ‘’how does one transcend one's past.’’

- We will see lots of rethinking of the past in the project, even the title is a kind of reference to the past. What about the future? As we discussed before: old models of society are not working anymore…

- I think we are going through a very critical period, not just in European history, but in world history. And it all goes back to the 18th century. What we are seeing now is a huge world rebalance of power. What happened in the 18th century is that Europe underwent a series of revolutions in philosophy, ideology, politics, technology, industry and demography that completely changed the face of the whole world. The first revolution was when the American colonies declared independence from Britain and this, like the subsequent revolution in France, was related to new ideas about Human Rights. The idea of human rights has its good side and its bad side. Taken in an abstract form is wonderful. But, often it’s used by governments as a weapon - some have or are given rights, others not. And there is no such thing as "complete" freedom - only relative forms of it.

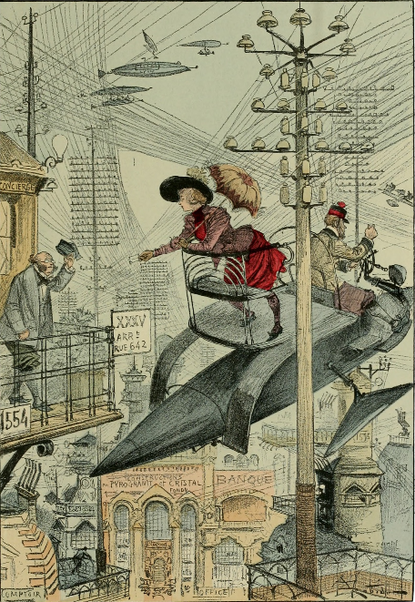

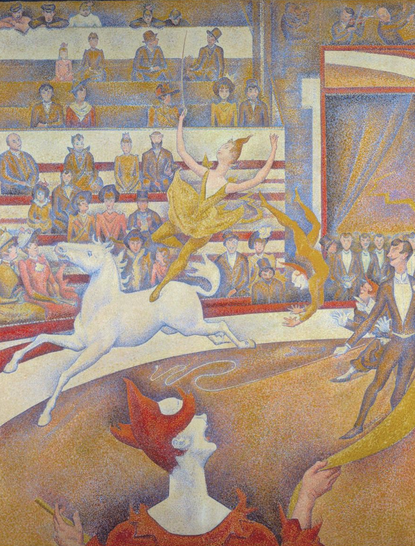

There were three big power masses in the 18th century: The western empires – Britain, France to an extent the Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese. Then the Ottoman Empire spread from Asia Minor over Central Asia, the Middle East and Northern Africa. Lastly, there was the Chinese Empire. During the 18th century, neither the Ottoman nor Chinese Empires modernised. Probably, they didn’t feel the need. And, as a result, they were overtaken by the increasingly global West, they were cannibalised and lost their power. But, what we see now is another huge change: the West is becoming less powerful and the others are catching up. The "Atlantic Rim" power balance of the last 250 years is coming to an end. China is now again influential, even Turkey has woken up. India is emerging from its colonial and postcolonial gloom. But the main problem throughout the democratic world is that politics is based to a greater or lesser extent on 18th century oppositional European models which are short term because they are governed by elections. Consequently the main objective of any Party is not so much to tackle serious long term issues that affect the fate of us all, but to hold on to power and get re-elected. The main problems that face the world can only been settled over time spans that have nothing to do with electoral terms. As a result politics is becoming increasingly irrelevant - like a circus in which some of the clowns are better than others - but essentially it’s not real.

- What you just said concerns the idea of the Apocalypse …

- Apocalypse here is in quotation marks. But I think sometimes you have to be prepared to destroy things to make something new. I am not talking about human life or nature but about hidebound, outdated institutions which we are brainwashed into thinking are necessary but which actually are a vast impediment to improving things.

- From this point of view the project is very optimistic...

- Yes, to be a skeptic you have to believe in the future. One has two choices: to be optimistic or pessimistic (and cynical). If you are going to be an artist you have to be essentially optimistic because art, if it is any good, has no limiting time scale and also you would never put yourself to so much trouble.

- When you started your work here you already had some impressions of Ukraine and about how to present the country to the world and the world to Ukraine. But, during the last few months you have gone much deeper into the local context - political, cultural and social. Has this experience raised a lot of issues for you?

- Well, to an extent, yes. But I don’t want to be in a position where I am working on a biennale in a particular country and then start to comment directly upon the politics there. Contemporary art is political enough in an open ended way without me having to make any kind of specifically orientated propaganda. Of course, there are some particular problems here as there are in Russia, or Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan. These are the shared problems of creating a contemporary culture for a new country. I am also working in another new entity, you can’t exactly say a state but an autonomous region, which is Hong Kong. It only gained independence in 1996 and the people who live there are now experiencing a huge confusion about who they are, what they are, what they represent.

- You have tremendous international experience with different culture contexts and attitudes towards arts and society. So you can really compare them. Do you see any difference between how the importance of an artist is recognised in Asia, Europe and here in Ukraine?

- Historically yes, there are differences. There is certainly not one discourse but many different discourses at work here just as there are different cultural and aesthetic traditions. Yet, in spite of what some nationalists might claim, no one is born knowing their own culture and language. They have to learn them....and if you can learn one set of values you can learn others and then begin to compare the similarities and differences. So in terms of aesthetics, although the "languages" may be different, the human values they express are very similar. It is only good artists, wherever they may live, who are aware of and are able to express such things in their work but certainly such a vision is to be highly esteemed wherever one may find it.

- What are your future ambitions? What would you like to do in future...?

- I would like to get one more institution open...

- Where?

- I don’t know, time will tell. Hong Kong is one possibility. That is one way to go. Another way is to do more big exhibitions.

Asya Bazdyreva