‘Isolation’: underground or a start of a cultural revolution?

You must love what you do.

Cài Gúoqiáng

Lately we have witnessed the process of contemporary art decentralization, which at last has gone beyond the city boundaries of Kyiv. And what is meant by this are not occasional ‘visiting’ projects, but actual systematic approach towards creating a cultural environment.

Cài Gúoqiáng. Moniuments of Shoulders. 27 ash painting made after the sketches of 18 local astists, as well as Cài Gúoqiáng hismelf. 2011, coal, salt, mining lights.

It was a year ago that the platform for cultural initiative ‘Isolation’ – a non-profit non-governmental foundation, occupying the territory of what used to be an insulation materials factory - opened up in Donetsk. And while the original name of the factory was kept, it does seem that it would have seem hard to come up with a better one: any region, situated at a distance from the capital, is, as are its issues, isolated.

Cài Gúoqiáng. Moniuments of Shoulders. 27 ash painting made after the sketches of 18 local astists, as well as Cài Gúoqiáng hismelf. 2011, coal, salt, mining lights.

That is why the emerging of an institution, which can not only stress local cultural and social problems, but also bring them out onto a global level, is an event of national measure.

The creation of the portraits for the 'Monuments of Shoulders' project.The process was broadcasted live on the internet

Between August 27th and November 11th ‘Isolation’ will be home to a site-specific-project ‘Cài Gúoqiáng: 1040 meters under the surface of Earth’. For the first time in Ukraine such great amounts of funding were given to a short-term project. Even such ‘giants’ of Ukrainian art-scene as PinchukArtCentre and ArtArsenal usually invest money into concepts that are limited to the artistic environment. ‘Isolation’ managed to go beyond that by realizing an interdisciplinary project, which could become the foundation for future socio-cultural change in the Donbass region.

The creation of the portraits for the 'Monuments of Shoulders' project.The process was broadcasted live on the internet

Having chosen Cài Gúoqiáng, ‘Isolation’s’ team has set foot on a quite complex path since someone who is a representative of a completely different culture might find it quite hard to address local issues in a local context. But the result of the artist’s work turned out to be very up-to-the point and so well-balanced, that it was really hard to give any extra comments after seeing it. Funnily enough, because of this total perfection and internal compositional harmony one might actually see a slight dissonance between the project’s conceptual and methodological correctness and the sociocultural realities of contemporary Donbass.

Cài Gúoqiáng.Lullaby. 2011, installation. 9 old mine-buggies, motors, found objects (Soviet era), soviet films, cartoons.

Cài’s art seems to be an illustration of Zen philosophy: the process is the main body of the work. The show, installed in the halls of what used to be a factory, is already the final part, or documentation, of the artist’s dialog with the community, the history and the culture of the region.

This dialog was first started back in May 2011, when Cài Gúoqiáng first visited local salt and coal mines and went up on a slagheap, talked to the locals. Since then, until the very opening of the show, the project remained totally interactive: local artist made sketches of coalminers and volunteers helped to make stencils for ash paintings and the actual works themselves.

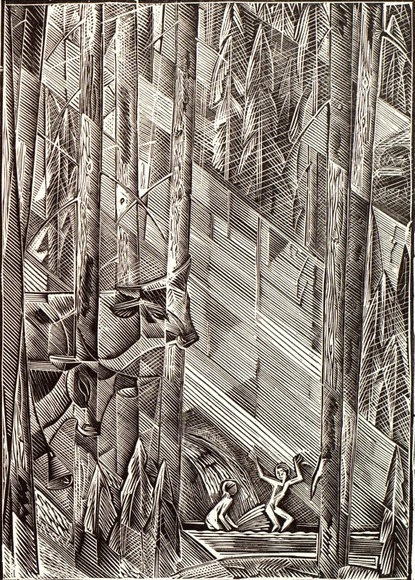

‘Monuments on Shoulders’ is a work that strikes one right away, acts synthetically since the viewer is totally immersed into its environment. The space of the gallery is metaphorically divided into two parts, with their floor covered respectively with salt and coal – two natural minerals that came to be symbols of this region. Cài made figurative mountains out of these two minerals, putting the portraits of coal- and salt-mine workers at the top of each. In order to see these works the viewer has to get to the top of each pile, which, to tell the truth, is not an easy task taking into account how unsteady the materials under one’s feet are. Through this the artist makes the viewer feel both the amount of effort that a miner’s job requires, as well as how underestimated it actually is. The sound that is created by walking on these hills is also an integral part of the work as if fills the space of the gallery and intensifies the effect for the viewers.

The making of the sketches for the project.

The miner’s portraits are standing on wooden planks that the artist calls shoulders. Such installation reflects the soviet tradition of carrying portraits of leaders at parades, except that Cài's canvases don’t represent idealized dictators, but depict heroes of everyday life, who risk their lives on a daily basis.

Another work, a dynamic installation called ‘Lullaby’ – is a composition of 9 old mine buggies that move very slowly and remind us of cradles. Each of the buggies is dedicated to a different topic, although all of them are bare references to the socialist part of the region. Everyday life, sports, society, was childhood – all these are addressed through specific soviet-era artifacts, enriched with video-projections onto the canopies of the ‘cradles’. Videos of German troops’ invasion during World War II and scenes of happy life under the Soviet rule, mixed with the sounds that the buggies produce intensify the effect of the work. Each of the buggies is a symbolic element of the chain of life; the last one of them is dedicated to religion but immediately provokes associations with death and cemeteries. In the vast space of what used to be shop #2 the viewer is faced with the nation’s past, with its utopian dream a of socialist future. Today, from our XXI century point of view, the realities of those times seem so very distant, but when faced with ‘Lullaby’ one understands that it is impossible to get rid of one’s own history, you can’t just erase it from your memory.

The artists himself led the first excurtsion of of the show for ukrainian and international journalists.

On first glance the projects can be seen as a commentary on the local history and social issues of the Donbass region, but if you stop and think for a moment you realize that it is actually a very personal work reaching out into the artist’s life and the history of his own people. Through this project Cài Gúoqiáng tries to make this history available in a different context, and by using material that is accessible by representatives of a different culture, the artist very easily achieves his goal. We can actually see the utopian dreams of the past, the past and dreams of a different nation that are so easily reflected in ours.

‘Isolation’ is situated on the outskirts of Donetsk and getting there might be a problem unless one knows the way. It is a kind of underground commentary on the city-life culture, which is still very provincial and hasn’t gone too far from its soviet ideals (the only difference might be in the amount of cool foreign words that are used in everyday life). Because of this, the hopes for it to become a beginning of the Donbass cultural revolution are, of course, overestimated, but it is only time that will tell of these repercussions are true.

Cài Gúoqiáng working on the ach painting for the 'Monuments on Shoulders' project.

A.B. This is a site-specific project, it corresponds to local space. You also mentioned using local context as inspiration. But it seems to me that this work is also very personal, it contains lot of references to Chinese history.

Cài Gúoqiáng: This is a show about a dream, a dream shared by many, something very innocent, a dream of socialism that humanity pursued since the very dawn of time. Of course, it might be hard to comprehend this, it takes time and effort.

This idea is especially obvious in the gallery housing the ash paintings, which are meant to refer to portrait of leaders but are actually portraits of 'simple' people. These are symbols of utopia that never came to be.

C.G.: These miners seen as heroes by many, heroes of all time. Because of their social status their life has never been easy. And today they are even more marginalized. We decided to offer them a chance to become part of the creative process, flip the roles, so to say. We gave them a chance to pose new questions.

… that the artist can't answer. You said that art can't change the world. But it can identify problems that exist in the society. Let’s come back to the question about the locality of the context: what problems can you identify here? Or is this just another question that I shouldn’t ask an artist?

C.G.: Although art’s existence can’t formulate laws, it can, though, help solve problems. Art can help identify questions that politicians should later deal with. Here you have philosophical debates about the fate of miners at different times: soviet and contemporary, and what place they occupy in history. Almost all of my works are historically contextual and this is what gives them an element of tragedy and irony. This might seem very simple at first, but becomes more complex when examined closely. This is actually the realest part.

To quote you: «We must be in the moment, be present in what we do, here and now». This reminds me of the Zen philosophy…

C.G.: Presence is a very important factor in art. Art has to be 'in the moment', in what one feels. That's why I keep stressing the importance on ‘happening’; it intensifies the feeling of being present here, of experiencing something, of feeling. It might be very hard to understand what is going on if this presence is absent.

The dialog between you, the Universe, the Earth, the people that you work with, is incredibly important for your work. Does this mean that the creative process is far more important than the work that it results in?

C.G.: The dialog with the coalminers, young artists and volunteers is indeed a very important part of my project. It is only through this dialog that I was able to present what you are looking at now.

About your other work, 'Lullaby': each buggy is addressing a different topic: sports, war, childhood, personal achievements. The last one, according to you, is dedicated to religion, but it seems to evoke associations with death and cemeteries. Because of this the entire work seems to refer to the cycle of life where each step is inescapable.

C.G.: This work is not just in dialog with the ideas of socialism, it is in dialog with the entire world. It is universal and presents the idea of the difficulties that one encounters when searching for better life. There might be something to think about for everyone. In a way, it is about spiritual crisis and helplessness.

Asia BAZDYRIEVA