An image made of fragments: Aleksandr Gnilitsky at the National Art Museum of Ukraine

The National Art Museum of Ukraine has recently been turning to contemporary art more frequently. In September-October the museum held a show of works by Aleksandr Gnilitsky, dedicated to the artist’s 50 birthday (1961-2009).

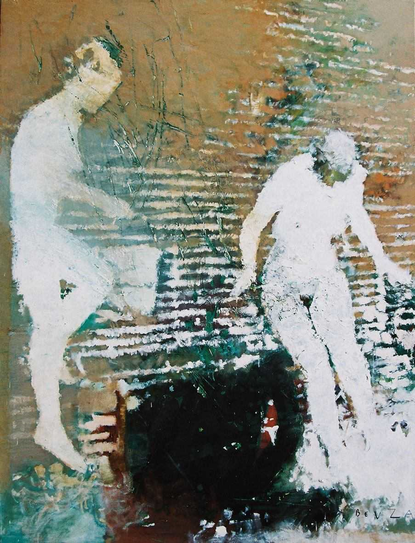

Flying Carpet

Article from ART UKRAINE #1 (1) 2011 September/October. ПАНОРАМА.UA

The name of Aleksandr Gnilitsky has long since become well-known in the recent history of Ukrainian art (1980-2000). However, unfortunately, it is not very often that we see his works on show in Kyiv. That is why the aim of the exhibition at the National Museum was to fill in this gap and to place the name of Aleksandr Gnilitsky on the national art-map. The museum itself owns only one work by the artist, and this, by all means, is far from being enough to even closely represent Gnilitsky’s contribution to contemporary art. That’s why it was so important to engage the artist’s family, friends, collectors, patrons and others in organizing the show. Members of the artist’s family Natalia Filonenko, Ksenia Gnilitska, Lesia Zaets, collectors Andrei Berezniakov and Anatoly Dymchuk eagerly offered Gnilitsky’s works of their possession to be loaned to the Museum for the time of the show, as did many of the artists friends and schollars reserching his work.

Aleksandr Gnilitsky at work

Aleksandr Gnilitsky is one of the pioneers of the so-called southern wave of Ukrainian art of the late 80s, although he wasn’t the first artist to turn away from painting, – a medium which he nevertheless loved, - and turn to video-art. In his work he used a lot of different media of contemporary visual art practice: interactive installations, work-in-progress pieces, growing art, kinetic sculpture, video performance and many more. It is important to remember that all this was done in the time when technological progress was still something very foreign to Ukraine, and all the pieces were done without any help from different devices and computer programs and only through the artist’s talent, imagination and ingenuity.

Aleksandr Gnilitsky is rightfully named one of the most unexpected artists of the Ukrainian art-scene. Being a very creative person, he repeatedly challenged his viewer with the ambiguity and multidimensionality of meanings in his works: this was due to the significant influence of neo-dadaist absurdism on his art. But even in the times when Ukrainian art was ruled by trans-avant-garde, Gnilitsky’s style went through several phases, constantly changing and developing: from “curly style”, greenish “wave painting”, black and white grisaille, to the at that time trendy “childish discourse”.

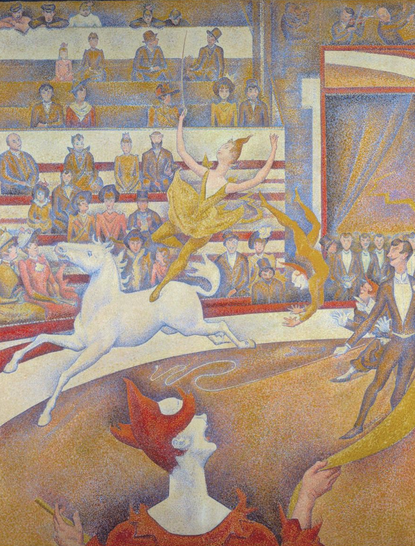

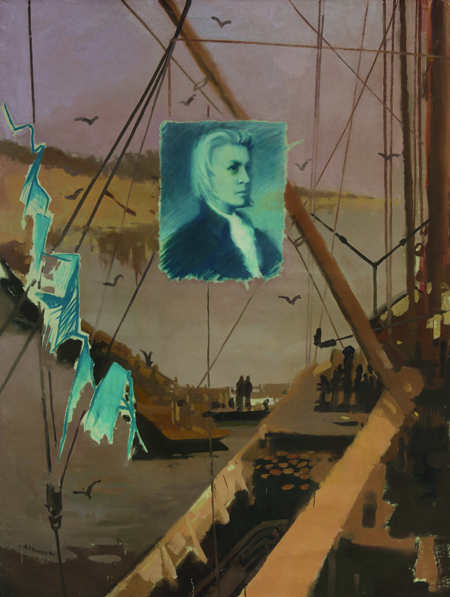

Self-portrait as Mozart.

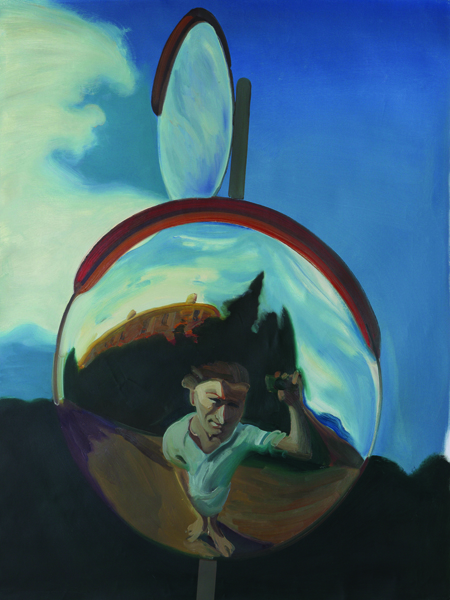

An important moment in Gnilitsky’s art, as well as the history of contemporary Ukrainian art in general, is his poem-performance Sleeping beauty in a Glass Coffin. The video, in which Morpheus, Eros and Tanatos came together in an absurdist feast of decadence is accompanied by a reading of the artist’s poem of the same title. Another video – Crooked mirrors – live paintings was made with the sole use of props from a “house of mirrors” which were bought for ridiculously small sum of money. The optical system built by the artist provoked a surprisingly strong flow of hallucination-like images.

In 2000 Gnilitsky’s style changes again. The artists engages in pseudo-narrative painting, re-coding existing images of characters from cult cartoons (Cheburashka, Crocodile Gena, Shtirlits and Mueller, Fantomas, Dracula, Mermaid). He also turns to a sort of iconization of every-day objects, which he turns into strange and mystical ones with the help of an illusionist type of written font.

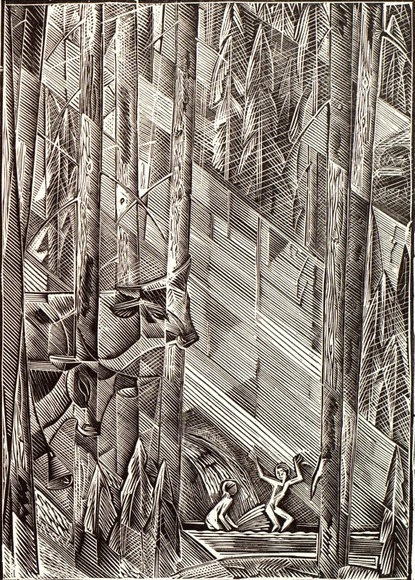

Self-portrait in a crooked mirror

On display at the National Museum of Art were Gnilitsy’s works spanning three decades of his career. But this was not a retrospective. Lesia Zaets suggested an idea, according to which the show would present the viewer with a collage-like image of the artist. The show included his self-portraits, portraits of him made by his friends, pieces that together form an idea about Gnilitsky’s persona. Personal photographs made by close family and friends, as well as staged photographs like those from Ilya Chichkan’s Gold of Ukraine, or shots by Aleksandr Shevchuk, Vasili Riabchenko, Kiril Protsenko and others.

To accompany all the images the curators also made a documentary, using existing footage, which showed Gnilitsky while working on different projects.

The show incorporated not only Gnilitsky’s solo pieces, but also the ones that he participated in as part of a group. For example, the public finally got a chance to see his famous video Crookes Mirrors (1993), a part of his installation which was presented at the Greenhouse Effect show at the Soros Foundation Centre for Contemporary Art (1997), and Death Dance (1996) anamorphosis object. The audience could also see photodocumentation of V.Tsagolov’s performance Karla Marxa - Père Lachaise (1993), a sketch of Gnilitsky made by A. Sai (early 2000), V. Trubina’s painting Youngsters at the Sea-Side (1992) which shows Gnilitsky and Golosiy, and hear the audioversion of Aleksandr Roitburd’s poem about the artist.

Chandelier

This type of dynamic and ambiguous portrayal is not accidental. Gnilitsky himself in his art avoided all kinds of dogmatic boundaries: his works were always a mix of play between truth and fiction, myth and fact. He himself became a part of a myth already during his lifetime, and today this myth surrounding his persona becomes part of his legacy and plays an important role in understanding his works.

According to Oksana Bashyrova, the show’s curator, essential to understanding Gnilitky’s art is his own idea that beauty is possible only as a miracle. He possessed a unique talent to turn chance, or miracle, into beauty. “His works, regardless of subject-matter of medium, were stripped of aggression and opened up the object’s hidden miraculous being,” – says Oksana Bashyrova. Most striking in this sense are his anamorphosis (1996), the Sleeping Beauty in a Glass Coffin video (1992) and Mediacomfort media installation (2005).

The curator also notes: “Gnilitsky is first and foremost a painter, the kind of great painter that nobody can accuse of being out-of-place and whose art will always be appreciated.”

The title of the show – CADAVRE EXQUIS – refers to the surrealist concept of using incompatible words and images. In this concept’s core lies a game in which all the players write a word on a piece of paper without knowing the preceding word. This game is named after one of such senseless sentences: Le-cadavre-exquis-boira-le-vin-nouveau (fr. “An exquisite corps drinks new wine”). The idea behind this game became a classic concept for surrealist practice, which, by combining incompatible ideas, created holistic works.

The show also offered a look at Aleksandr Gnilitsky’s persona through the prism of his life, his friends’ impressions, as well as works, which the curators managed to bring together in one show. Connecting hundreds of pieces, the show presented a well-rounded idea of the artist’s work, life and him as a person. It presented Gnilistky’s art through his multiple roles – father, friend, artist, hoaxer, - roles which he played throughout his entire life. It presented his life as intertwined with numerous myths, interpretations and a quest for beauty.

Анна Ландихова